Ready: You may be wondering if you’re ready to write. What – exactly – signals readiness?

Set: Or you may be wondering what must be set up and how.

There’s no dearth of recommendations. Having found what they need to write, writers are not shy about describing – and even prescribing – the conditions that made their writing possible. Some conditions have been anointed with authority and convey a threat.

EVALUATING THE RECOMMENDATIONS

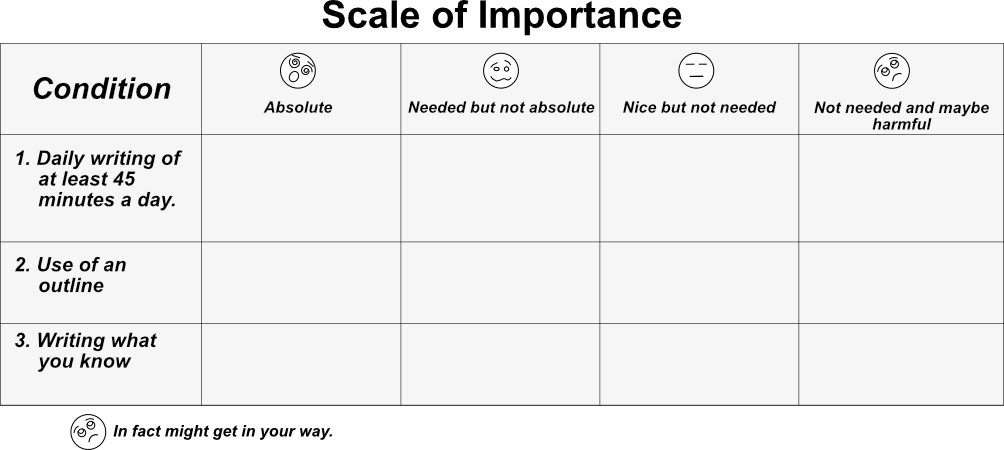

I developed a Scale of Importance that might help you consider advice from writers – including me – about how to write.

APPLYING THE SCALE OF IMPORTANCE

You probably noticed that I filled in the part of the Scale called “Condition” with three recommendations new authors often hear:

- Daily writing of at least 45 minutes a day.

- Using an outline

- Writing what you know

Do You Need to Write 45 Minutes a Day?

Think of this recommendation in terms of both frequency and length of time per episode.

My Rating: Nice But Not Needed.

Some Thoughts About My Rating:

It’s great if you can write daily for a given amount of time. But life sometimes gets in the way, and we manage time in different ways.

Minutes

What’s magic about 45 minutes? For some, three-quarters of an hour may provide enough time for writers to reread what they wrote the day before. For others, that much time may provide a warm-up period for expunging all the words that have been rattling in their brains for 24 hours and then fifteen minutes of serious writing followed by a cool-down for rereading new writing.

Annie Dillard, American author of poetry and both fiction and nonfiction, describes her warm-up as doodling “deliriously in the legal pad margins,” fiddling “with the index cards” she uses to capture her ideas, and rereading “a sentence maybe a hundred times, and if I kept it I changed it seven or eight times.”

For others, 45 minutes is far too long for sitting at a computer or with a pen and paper at a desk. Still others would prefer a more extended time.

Number of Words/Pages

Some authors substitute number of words for time. A thousand words is between three and four pages double-spaced, using a 12-point font, about 300 words per page. Others substitute number of pages, a minimum of five pages, for example.

The Whole Thing

American “King of Horror” author, Stephen King, thinks in bigger chunks of time: how long it takes to finish a book. He aims for having a first draft after about three months of writing. To produce that first draft he writes, “I like to get ten pages a day, which amounts to 2,000 words. That’s 180,000 words over a three-month span, a goodish length for a book – something in which the reader can get happily lost, if the tale is done well and stays fresh.” Even if he’s struggling, “only under dire circumstances do I allow myself to shut down before I get my 2,000 words.”

Annie Dillard claimed, “It takes years to write a book – between two and ten years.” Others, such as Flaubert, she wrote in The Writing Life wrote “steadily, with only the usual, appalling, strains. For twenty-five years he finished a big book every five to seven years.”

Others, she wrote, took less time. Faulkner, for example, “wrote As I Lay Dying in six weeks; he claimed he knocked it off in his spare time from a twelve-hour-a-day job performing manual labor.” Thomas Mann, “working full time, wrote a page a day – a good-sized book a year. At a page a day, he was one of the most prolific writers who ever lived.”

Daily

For many writers, the most important word in the imperative “Writers must devote at least 45 minutes a day to their writing, whether or not they have something to write” is the word “daily.” I hear the thunder of threat in this dictum. “Or what?” I wonder.

Also, there’s not much room to maneuver in this requisite. DAILY. Julia Cameron, an American who wrote The Artist’s Way and The Right to Write, suggests this is “what people, erroneously, call ‘discipline.’ What a thankless word that is – and how beside the point. What a better word, or thought, the term ‘routine.’ We need to establish a creative routine, a rote-do-able, daily something that is there to fall back on.”

She writes daily, however: “I write three pages of longhand every morning. It doesn’t take me long, but it takes me far.” Some is usable, some not.

How I Use Time

Like Julia Cameron, I “don’t want to make such a big deal out of writing. I like writing to be more portable and flexible. I like writing to be something that fits into cracks and crannies. I don’t like it to dominate my life. I like it to fill my life. There is a big difference.”

I confess that I don’t write daily, at least not physically, but I am always writing in my mind. If you read my second blog post, Always on My Mind, you know what I mean. I am always writing, so when I sit down to write, my words decant onto the page without effort. What flows onto paper is far from perfect, sometimes just adequate for catching what I’ve been thinking about, and I know I’ll revise and revise and revise, and then edit.

I write for as long as it takes for me to pour out what I hope will develop into a drinkable wine (to continue the metaphor). Sometimes several hours, sometimes a whole day. If I haven’t drained everything out by the time my body has moved beyond aching to throbbing, I’ll type notes to remind myself what was next. In fact, I always end with what I want to do the next time I write. . .and that way my mind has something to focus on right away.

This is probably not the best way for me to manage writing time. If it’s time to write. . . it’s time to write, as long as it takes me, and I can be insufferable until I’m finished. Just ask my family.

What You Might Do About Time

Since you can’t just make more of it, put your use of it for writing to a few questions:

- Am I just hiding behind my fear of having nothing to say? Or not being good enough? Or some other blockage?

- Am I ready and eager to write – and disappointed that I can’t write on a particular day?

- Am I compelled to write a note to myself about what I would have written if I had been able to write that day?

- Could I live with the condition of “daily” or do I need to set a time or number of pages requirement?

- Would I really write something if I let myself write when I feel like it?

Should you Prepare an Outline?

Think of using an outline as construction of a classic outline before writing, with at least two main points (I and II) and at least two sub-points (A and B) for each main point. Before you read further, use the Scale of Importance to determine how you rate the importance of an outline.

My Rating: Not needed and may be harmful.

Some Thoughts about My Rating:

I’m a jotter. As I think, I like to capture what comes to mind. Sometimes, I naturally have main and secondary points, and sometimes I’ll actually use the formal style of Roman numerals for the main points, capital letters for the secondary points, and (if warranted) numbers for the tertiary points. I may even worry about having only one secondary or tertiary point. I was taught that if you are going to divide a point, you must have at least two subdivisions (otherwise, the point will be, well, just a point). Somehow, I’ll fix the mechanical error before continuing the process.

I most often use an outline when I’m writing nonfiction, but I usually abandon it after capturing my first two points and any subpoints and get into the writing . . . to see where it will go before continuing the process of outlining. So, I may complete an outline but only after I’ve started writing. Similarly, I may abandon an outline if it doesn’t lead me to the purpose of the piece I’m writing.

I rarely use an outline for fiction. It’s just too restrictive. Jotting is usually enough for me to capture ideas, development possibilities, connections, etc. When I first read Annie Dillard’s The Writing Life I adopted her method of notecards, one idea (with sufficient development to remind me of my thinking) per card. Like her, I would sort the cards to see what I had. When stickies became widely available, I used them instead of notecards.

In her book about writing, Bird by Bird, Anne Lamott described her use of notecards. She kept them throughout her house and in her car and grabbed one and put it with a stubby pencil into the back pocket of her jeans when she took walks.

Outlines can dam the flow of writing. They become a discipline themselves, much more than a routine. They can become a taskmaster. They force linearity and logic. They may dullen creativity and flow.

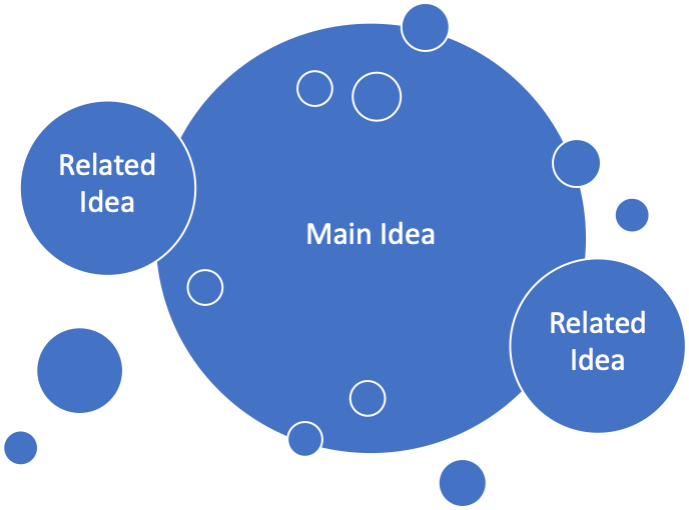

On the other hand, they do show the relationship among ideas. Mind maps show relationships better than outlines, however. Here’s a simple one:

Should You Only Write About What You Know?

Think of this condition as, literally, writing what you know or have experienced, nothing else. Before you read further, use the Scale of Importance to determine how you rate the importance of writing only what you know.

My Rating: Needed But Not Absolute

Some Thoughts about My Rating:

What if you’ve never been to another world, but you want to write about humans in that world?

What if you wanted to write about the future, but of course, you’ve only lived since (you name the year)?

What if you wanted to write about China in 1913, but you didn’t go to China until 1999, and you visited only a few places, not the whole country?

What if you wanted to write a horror story about a mysterious creature that craves human blood, but you’re never enjoyed that cuisine or known anyone who did?

You probably have no trouble thinking of stories, articles, books, and poems that have been written about these subjects. For example:

What if you’ve never been to another world, but you want to write about humans in that world? (How about Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland or The Chronicles of Narnia? How about The Lord of the Rings?)

What if you wanted to write about the future, but of course, you’ve only lived since (you name the year)? (How about The Handmaid’s Tale or The Hunger Games? How about Fahrenheit 451?)

What if you wanted to write about another country at a particular time in history, but you have never been in that country or, at least, not during that time period? (How about Born a Crime or Memoirs of a Geisha? How about The Kiterunner or The Snow Leopard?)

What if you wanted to write a horror story about a mysterious creature that craves human blood, but you’re never enjoyed that cuisine or known anyone who did? (How about Fledgling or Interview With the Vampire? How about Salem’s Lot or The Twilight series?)

Actually, my own book is about China from 1913 to 1937 and I have never lived in China and I was born after 1937. (I traveled to China in 1999 but visited only a few places during my brief time there). So, I had to think very carefully about how to be truthful and honest in my writing.

“Good writing is telling the truth,” Anne Lamott said. “We are a species that needs and wants to understand who we are. . . .”

So, writing about what we know is needed, but not absolute. We may have to conjure what goes into our book (fiction or nonfiction), but we must do so as honestly as we can.

Notes:

- We don’t always know these in advance of writing (hence, an outline may be superfluous or misleading), but we work through them as we write and rewrite.

- I will develop these ideas in future blogs.

- They apply to fiction and nonfiction.

WHAT WE KNOW about the elements of any book:

The idea(s) (beliefs, values, morals, truths) that resonate as one or more themes

They may be antithetical to anything we personally or societally accept, but they are truthful and honest because they relate to what we know, even if they are opposites: Example: Kindness resonates in many societies, but in one particular book, let’s say, the guiding principle seems to be the opposite, animosity. Is that dishonest? No, it’s truthful because it is possible in relation to kindness.

The situation(s) that manifest (which are better known as plot)

These are truthful if, no matter what they are, they display logic and/or sequence.

There are one or more protagonists (working FOR something).

There are one or more antagonists (working AGAINST the protagonist or something else).

There is conflict. It can be internal, external, or combination of these.

There is resolution (or honesty about the impossibility of a resolution).

They can be one of someone’s “basic narrative structure.” For example, Christopher Booker lists several narrative structures his 2004 book The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories.

The character(s) that operate (and how and why they operate as they do)

No matter how different from anything we know, there is some truth in any character. It is motivated to do something. It does something. There are consequences. Characters engage in situations (or plots).

A model of the environment (characteristics of space, time, and other features within which characters operate.

WHAT WE RESEARCH about these elements:

I didn’t know much about China, especially between 1913 and 1937, but I ingested everything I could. The book is loosely based on the life of my grandmother who died when I was 16. Thank goodness she wrote her own book about her husband. I nearly memorized that to learn something about her. She corresponded through hundreds of letters (many of which I discovered in archives) and photographed everything she could. I also interviewed my mother and aunt who had interviewed her before she died and had written their own accounts of her life. I traveled in China (including up the Yangtze) with my mother to experience the places my grandmother knew and conducted significant research to understand the life of this remarkable woman. I bought books out of print, sought scholarly papers on anything that seemed to relate to my story, and corresponded with or interviewed those who seemed able to shed light on my story.

The task here is to think tangentially. Even if you think your book is so extraordinary that nothing has been written about any aspect of it, don’t give up. Something may inform you or lead you to think about something important to the truth of your book.

Here’s a trivial example: As far as I know, my grandmother never toured a pagoda. I saw no need for the character based on my grandmother to tour a pagoda. But when I read that there were pagodas high atop the mountains lining the Yangtze, I decided I needed to know more about them.

The first book I wrote about my grandmother was a collection of the facts I knew about her and facts I discovered through research. It was a door-stopper and dull, but I needed to complete it before I could write the novel Through the Five Genii Gate.

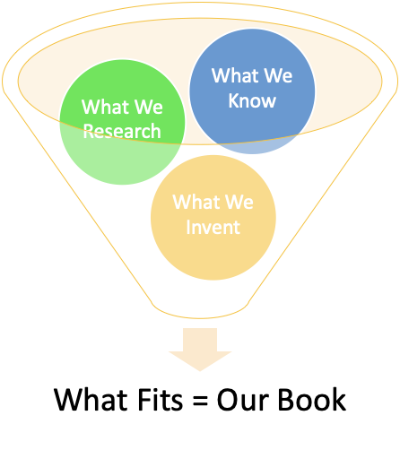

WHAT WE INVENT:

Finally, there’s what Brenda Ueland called “creative impulse or spirit.” Quite a character, Brenda Ueland was, judging by her pictures in If You Want to Write: A Book About Art, Independence and Spirit. Ueland declares: “I have proved that you are all original and talented and need to let it out of yourselves: that is to say you have the creative impulse” (10). Her 1987 book features two photographs, the first taken in 1938 of a rather demure looking Minnesotan; the second taken in 1983 of a woman who is enjoying her bohemian life. She is dressed in a broad-striped jacket, a vest, a frilly blouse, a bow tie, and a mop of hair. She died at 93 in 1985.

You could invent first, of course, writing whatever you imagine, letting “the ardor and the freedom and the passionate enthusiasm [well] up in” you. (14) In fact, she would say that the other ingredients (what we know and research) are REASON which “continually nips and punctures and shrivels” the others.

Begin where you want but let all three “balls” in the funnel influence you and each other: what you know, what you find out through research, and what you imagine.

WHAT FITS:

Imagine an aerator at the bottom of the funnel, like that in a spout which funnels water from its source into a small container such as a sink or basin. The aerator mixes the water with air and regulates its flow. Now imagine a writing aerator that fits everything together – what you know, what you learned through research, and what you imagined. That is how a piece of writing becomes truthful and honest.

(I know, I know, that’s pretty far-fetched: A metaphor extended too far!)

IN THE NEXT BLOG:

Lots of writers – including me – have prescriptions for writing. Based on our own experiences, we feel rather free to recommend THIS or dissuade you from doing THAT.

I’ll discuss a few more of these opinions in BLOG #4, according to the categories of the Scale of Importance:

Absolute

Needed But Not Absolute

Nice But Not Needed

Not Needed and May Be Harmful

Please feel free to disagree with me (or signal agreement) by commenting or sending me an email at 5genii@gmail.com.

Also, remember that no matter imperious – even threatening – a recommendation may seem, you are in charge. Your job is to get yourself ready to write in your own way. Someone’s opinion (especially from an author you admire) may prompt you to do THIS or avoid THAT, but you get to decide. You even get to audition a strategy and then decide to improve on it, keep it as is, or abandon it.

APPLICATION FOR NONFICTION

The examples I’ve used in this sub-section about writing what you know are mostly fiction. However, the advice itself seems more applicable to nonfiction. By definition, nonfiction is prose that is based on facts, real events, and real people. Naturally, it would be about what you know. Or would it? The published books and articles I have written are considered nonfiction, but I have discovered that they contain copious fiction, too, in the form of examples, illustrations, cases, narratives, descriptions, patterns, representations, parallels, models, instances, prototypes, or specimens. I have never created these “out of whole cloth” – a cliché that means without basis in fact or reality. Rather, like the examples I gave for the “What Ifs” of writing, they have always proceeded from what I knew or experienced, what I learned through research, and what I could imagine – all fitting together to create an honest piece of writing.

One example is my book, Engaging the Disengaged: How Schools Can Help Struggling Students Succeed. It was based on the story of a school that was making changes to help all students learn. The school in the book was not a real school. It was a composite of many schools that I had worked in and studied. It was an honest picture of how schools go through change, based on my knowledge, research, and imagination, all of which fit