Giving Chase

Starting to write never stops. . .until it stops. That may sound discouraging. Are writers always starting to write? Well, yes. Each time a writer writes the next word, sentence, paragraph, section, or chapter, the writer is starting to write. Each time a writer rereads what has been written and revises or edits, the writer is starting to write. Everything that matters when you’re starting, matters when you are continuing:

- · Choosing the first word and then the next and the next (Blog #7);

- · Considering audience, purpose (and attitude) (Blog #8);

- · Finding the beginning of whatever you are writing, sometimes in the middle (Blog #9); and

- · Setting the pace (Blog #10).

It helps me to think of the continuous process of writing as giving chase. You give chase until you have caught what you want. Then, you can write THE END.

When I checked the derivation of the word phrase giving chase, I learned at vocabulary.com (https://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/chase) that “To chase is to follow or go after someone or something you want. This activity is called a chase. Dogs chase cats, cats chase mice, and mice are in big trouble. The word chase tried to run away from the Old French word chacier for “to hunt or strive for,” but we caught it.”

The verb give is in the present progressive tense because that form indicates that the action is continuous. It started in the past (as you were getting ready to write) and it will continue as you write. It may become past tense when you have finished what you have written. Then you’ll be able to say, “I gave chase to my writing.” Done!

This blog and the next three blogs address what you as a writer do as you continue to start writing. This blog and the next two will discuss fiction, as follows:

Blog #11 Pursuing Plot

Blog #12 Courting Characters

Blog #13 Endeavoring Everything Else

The object of the chase in Blog #14 “Navigating Nonfiction” is obvious in its title.

The Chicken or the Egg

Which came first: the chicken or the egg?

Which comes first: plot or character?

Both questions are, in fact, trick questions. Generally speaking in terms of chickens and eggs, eggs came first. Before there were chickens, there were dinosaurs, fish, reptiles, and other creatures which lay eggs that yielded (surprise) dinosaurs, fish, reptiles, and other creatures. Gradually, these eggs and the creatures that laid them morphed into organisms that were not quite dinosaurs, not quite fish, not quite reptiles, and not quite like the creatures that had laid them. Some reptile eggs, for example, cracked open to reveal what we would have described as bird-like had we been there. Over time, a reptilian bird or a bird-like reptile laid an egg that looked like a chicken, and the world was never the same after that.

Specifically speaking, there can’t be a chicken egg unless a chicken lays one.

So, eggs came first generally; chickens came first with reference to chicken eggs specifically.

Just so, as Keston Harris noted in Your Story Is Nothing Without Its Characters (Sep 23, 2020): “You can’t have a good plot without well-written and complex characters. Likewise, if your characters are written well, their interactions and conflict will weave the plot. The two build each other up. It’s a partnership, not a ‘take your pick.’”

It’s a Matter of Emphasis

Creators

Creators of media (writers of nonfiction, books, stories, poems, articles; online publishers; podcasters; YouTubers; movie and television scriptwriters, producers, directors, etc.; video game creators; social media influencers, and others) emphasize either plot or character or both. Sometimes they base the appeal of their creation on its classification as character-centered or plot-centered. Example: “For a deep dive into the psychosis of a pick-pocket, watch _______________.” Or, “Practice deep breathing before you see this breath-taking thriller.”

CHARACTER-DRIVEN?

Consumers

Consumers of media (readers, viewers, listeners, game players, etc.) may search for, choose, and consume material they think is either character-driven or plot-driven, but not often both at the same time. Example: “I want a streaming series that looks at how a child grows in the face of trauma.” Or, “Keep me on the edge of my seat.”

So, briefly, what are some of the characteristics of plot-driven and character-driven media? Here’s are a few:

| Character-driven writing is likely to be: | Plot-driven writing is likely to be: |

|---|---|

| Slow and in-depth | Fast and exciting |

| Soothing | Tense |

| Deep and complex | Shallow and relatively simple |

| Focused on internal struggles | Focused on external struggles |

| Introspection and inner dialogue | Dialogue with others |

| Focused on the journey | Focused on achieving one or more goals |

| Themes and meaning | Action |

Here are some examples of each type of focus:

| Character-Driven | Plot-Driven |

|---|---|

| The Catcher in the Rye | The Lord of the Rings (except for Legolas’ character development) |

| The Handmaid’s Tale | Alien (movie) |

| The Kite Runner | Land of the Lost (movie) |

| Anything by Jane Austen | Genre fiction such as science fiction, fantasy, horror and thrillers. |

| The Midnight Library | Jurassic Park (movie) |

| A Man Called Ove | Guardians of the Galaxy (game0 |

You may very well disagree with some of the examples as well as have some examples of your own. Let me know.

WHAT PLOTS DO THESE PICTURES SUGGEST?

Mixing Both Character-Driven and Plot-Driven Approaches

For both creators and consumers, the best solution to the chicken and egg conundrum is to have a good mix of both. Recall what Keston Harris wrote about how plot improves when characters are well-written and complex; also, characters fully emerge when there is a plot full of interaction and conflict.

Here are some typical ways of looking at the mix of plot and character together:

- The plot consists of the natural consequences of characters’ actions, interactions, conflicts, motivations, personalities, etc.

- The characters drive the plot; they are agents of the actions in the plot.

- Events arise from characters’ otherwise inwardly focused goals and motivations.

- The plot necessitates character development, both internal and external.

- The plot gives characters a chance to experiment with new-found understandings, thoughts, and creativity.

- Characters’ values give plots their raison d’être.

- Plot occurs because characters act and interact in meaningful ways.

- Escalating plots require continued character growth.

- Having external events lead to internal reflection.

So, what media make good use of plot to drive character development AND use complex and developing characters to drive exciting plots? Here are some of my ideas:

The Harry Potter series of books and movies

The series Game of Thrones

Charles Dickens’ Christmas Carol

Gone Girl by Jillian Flynn

George Orwell’s 1984

Where the Crawdad’s Sing

Star Wars series

2001 A Space Odyssey

Stand By Me (film)

You may very well disagree with some of the examples as well as have some examples of your own. Let me know.

Finally, before we dig into plot, here are two examples of the plot/character relationship from my book Through the Five Genii Gate:

| Character Before | Plot Element | Character After |

| Kathryn has been widowed and is trying to make her own way in China, working, taking care of her three children, and getting a book published. According to the standards of the time, she is brave and resourceful. | Suddenly, the Japanese advance on China prior to World War II. Somehow Kathryn must get herself and two of her children out of China and find her son who is alone and missing in one of the coastal cities the Japanese bombed. | Kathryn discovers in herself the courage, tenacity and bold thinking that get her and her children to the United States. |

| Lucy, Kathryn’s youngest daughter is a typical ten-year old: carefree, careless, happy-go-lucky, innocent, a jokester, and a girl without responsibilities. She is self-focused. | Expecting a nice hiking trip on Mt. Emei, Lucy has to face danger, the unknown, and fear as she, her sister, and their mother make their way from a war-torn China to the U.S. | As they escape China, Lucy begins to develop more responsibility, though she is still happy-go-lucky. When her mother has a nervous breakdown, Lucy begins to look outside her own needs and cares for her mother and sister. |

| Emma, Kathryn’s oldest daughter immediately attends to the needs of her mother when her father dies, putting aside her own grieving. “I will take care of you,” she tells her mother. | Little-by-little Emma backs away from caring for her mother as they travel up the Yangtze to vacation on Mt. Emei. She begins to “have a life.” | Unfortunately, Emma must step in again to take care of her mother and her sister as they make their way from the perils of China to the safety of the U.S. At last in the U.S., she can reveal to her mother how she turned from carefree teen to caretaker in the family when her father died. Can she go back to attending to her own needs? |

These three characters were affected by plot, but they didn’t have much effect on plot, at least not at first. They could do nothing about the Japanese seizing control of China. However, the plot might have been altered if these three characters, especially Kathryn, did not find ways to change to survive.

What is Plot?

Fiction is about plot and character (and all the other aspects of writing, such as setting, theme, voice). In a Venn diagram, the interaction is almost whole, but not quite.

I say “almost complete” because the author may include something about character that seems to have no relationship to the plot. . .or some aspect of plot (a piece of backstory) that seems to have no relationship to one or more of the characters.

In a good book or story, the plot does not exist to give the characters something to do, nor do the characters exist to advance the plot. Character and plot work together. They are interdependent; they affect each other. And they affect all other aspects of a narrative: setting, theme, symbolism, voice, point of view, and style, for example.

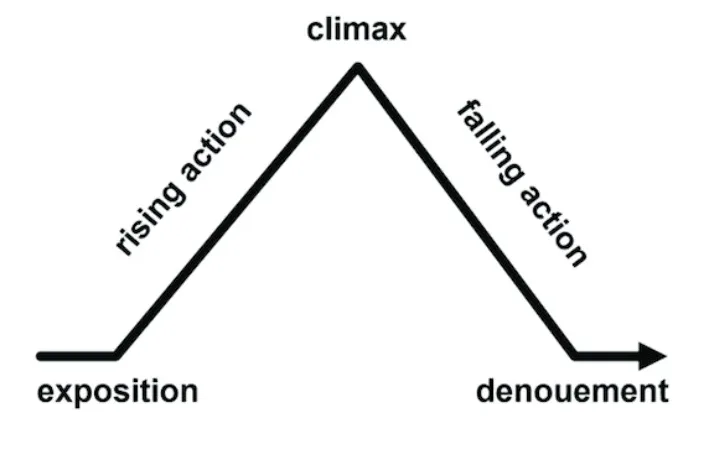

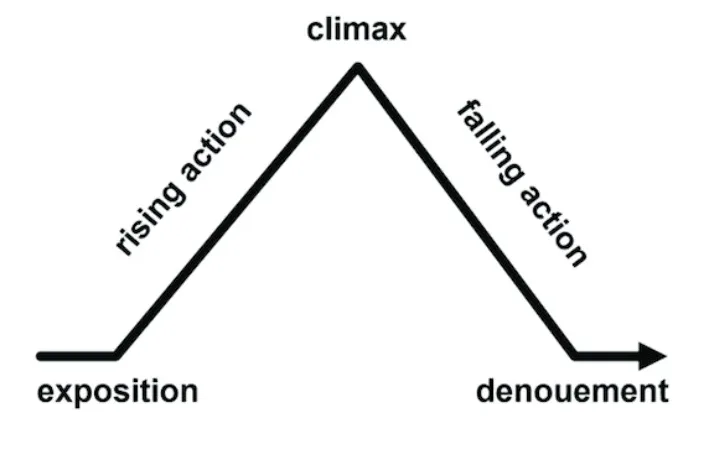

How they get together is another matter. A writer may say, “My novel is character driven.” Perhaps this means that the writer conceptualized character first and then invented a plot that would reveal the character and allow for growth. A writer may say, “My novel is plot driven” which indicates the writer may have an inciting incident in mind and follows it through with rising and falling actions, a climax, and a denouement. Along the way, characters present themselves, with one or more them emerging as the main character(s).

Although I am separating plot and character for the purposes of this blog, I recognize that they are perfect for each other in a good book. Although I separate both plot and character from the other considerations, such as setting, I acknowledge that plot and character work well in the home made for them.

Defining Plot

You may have noticed that I wrote the word “STORY” in the Venn diagram above. I used the word story to avoid using plot in usual sense and then as a word for the pairing of plot with character. Although many still use them interchangeably, story is bigger than plot, which is a series of events that – with other elements – comprises a story. According to the website https://www.bbcmaestro.com story is what your book is about, and plot is the sequence of events that makes the story happen.

Eudora Welty, American short story writer, novelist, and photographer who won the Pulitzer Prize, wrote in One Writer’s Beginnings that the “frame through which [she] viewed the world changed.” (90) She moved from seeing a story as scenes to seeing them as situations, and then “greater than all of these is a single, entire human being who will never be confined in any frame.” (90) She described writing a story or novel as

one way of discovering sequence in experience. . . .Connections slowly emerge. Like distant landmarks you are approaching, cause and effect begin to align themselves, draw closer together. Experiences too indefinite of outline in themselves to be recognized for themselves connect and are identified as a larger shape. And suddenly a light is thrown back, as when your train makes a curve, showing that there has been a mountain of meaning rising behind you on the way you’ve come, is rising there still, proven now through retrospect.” (90)

What a lovely way of describing plot and illustrating the connection between plot and character. Stephen King, a very different kind of author, saw plot as situation. He explained:

You may wonder where plot is in all this. The answer – my answer anyway – is nowhere. I won’t try to convince you that I’ve never plotted any more than I’d try to convince you that I’ve never told a lie, but I do both as infrequently as possible. I distrust plot for two reasons: first, because our lives are largely plotless, even when you add in all our reasonable precautions and carefully planning; and second, because I believe plotting and the spontaneity of real creation aren’t compatible. (163)

He adds:

The making of a story is that they pretty much make themselves. The job of the writer is to give them a place to grow (and to transcribe them, of course. (164)

I lean more heavily on intuition and have been able to do that because my books tend to be based on situation rather than story. . . .I want to put a group of characters (perhaps a pair; perhaps even just one) in some sort of predicament and then watch them try to work themselves free. My job isn’t to help them work their way free. . . but to watch what happens and then write it down. (164)

I rather like the idea of situation. Although I thought of character first because I was basing Through the Five Genii Gate on the life of my grandmother, I quickly moved to situation, which I called an episode. And then I went on to the next logical episode, caused by what Kathryn did in the first one. . .and so on.

King “has never demanded of a set of characters that they do things my way. On the contrary, I want them to do things their way.” (165)

What I read into that declaration is the futility of an outline. See Blog #3: Ready. . .Set . .Write: Conditions That Lead to Writing Success for more about outlines for writing fiction.

If you think that the word plot prescribes an outline of events, you’re in agreement with writer Anne Lamott who wrote,

My students assume that when well-respected writers sit down to write their books, they know pretty much what is going to happen because they have outlined most of the plot, and this is why their books turn out so beautifully and why their lives are so easy and joyful, their self-esteem so great, their childlike senses of trust and wonder are so intact.

She knows no one, including herself, who writes like this. Everyone “flails around, kvetching and growing despondent, on the way to find a plot and structure that works. You are ready to join the club.” (85)

She recommends, “in lieu of a plot you may find that you have a sort of temporary destination, perhaps a scene you envision in the climax. So you write towards this scene.” (85)

Here are some other words that might help you think of plot beyond an outline and intertwined with character:

Action

Causality of Events

Design

Development

Events

Incidents

Main Events

Narrative

Plan

Scheme

Sequence of Events

Storyline

Strategy

Structure

Thread

Unfolding

What Happens

Plot Outline

Having just advised you not to think of outlining a plot for your fiction, I am now going to seem to contradict myself. Please do not outline, but do visualize, conceptualize, and consider these elements of plot.

First, visualize an upside-down V, like this:

This is a basic diagram with a beginning (Status Quo), middle (Rising Action, Climax, and Falling Action) and end (Final Outcome). Most short stories and novels have more than one rising action – climax – falling action sequence. They are more likely to look like one or more mountains:

Usually, a short story or novel will have several rising action-climax-falling action sequences, culminating in a final outcome. I added denouement which means that all the details are wrapped up so that there can be a final outcome.

Other Words for Plot Elements

I like French (the language) and the word denouement, so that’s why I added denouement to Final Outcome in the mountain sketch above. I find that substitutions make me think a bit harder than a common word would, so I really have to THINK about what a denouement is. Give the plot elements your own words to give yourself a different perspective about what you are doing. Here are a few substitutions to consider:

| PLOT ELEMENT | Status Quo | Rising Action | Climax | Falling Action | Final Outcome |

| Other Words | Stasis | Quest | High Point | Resolution | |

| Other Words | Beginning of Story | Inciting Incident | Critical Choice | Outcome | End of Story |

| Other Words | Backstory* | Trigger | High Spot | Consequence | Denouement |

| Other Words | Opening | Choice | Turning Point | Result | Revelation |

| Other Words | Exposition | Reversals | Most Intense Point | Satisfaction | Conclusion |

| Other Words | Introduction | Trigger | Crisis | Catharsis | Answers |

Other Words | Circumstance | Conflict | Pivotal Moment | Revelation | Future Possibilities |

| Other Words | The Setup | Challenge | Trial | Aftermath | “Lessons Learned” |

| Other Words | Struggle | Wrap-up | Reflection | ||

| Other Words | Dilemma | Clarification | |||

| Other Words | Build-up |

Here is an example of plot diagram from the first part of my novel Through the Five Genii Gate, using words I prefer for the elements of plot:

EXPOSITION (STATUS QUO): In 1937, Kathryn, a widow, and her daughters are traveling up the Yangtze River for a summer of hiking on Mt. Emei, which is beyond Chungking, while her son attends a YMCA camp on the eastern coast of China. She thinks back on the trip so far.

CHALLENGE (RISING ACTION): When they get to Chungking, they are turned back immediately because all traffic on the Yangtze has stopped. This time, the Japanese invasion is serious; they have conquered the coastal cities and Shanghai (where the family lives) and are advancing up the Yangtze, committing atrocities and looting and burning towns as they go. Where will the family go? What has happened to the boy in the family who was on the coast? How will they survive? Will they need to leave China permanently?

CLIMAX: They resolve this problem by rushing to find a place on the ship they had taken upriver, now teeming with other refugees also going downriver, none of whom can believe that the situation is serious this time and all of whom do not know what to do. They settle in a makeshift cabin, worry about what’s happened to family and friends in Shanghai, and wonder what to do next. At the next port downriver, they meet a member of the U.S. Consul Office who suggests a temporary solution in Kuling but also makes improper suggestions to Kathryn.

FALLING ACTION: The challenge is temporarily resolved when Kathryn and her daughters endure an arduous trek from the river to the beautiful mountain retreat of Kuling, but many questions remain.

DENOUEMENT: They try to contact Kathryn’s son but cannot find him. They contact everyone else they can think of within China and in the United States. At least they are away from immediate danger, though Kuling is buzzed by warplanes nightly and they still have to resolve their other questions.

Of course, this is simply one of the plot sequences that make up the “mountains” of my book. Sometimes, the falling action is so slight or subtle the reader might not even notice it. Sometimes, the final outcome does not feel the least bit final, just temporary. Sometimes, there doesn’t seem to be a denouement. Perhaps the lack of a final outcome or denouement for one or more of the episodes feels like cliffhanger, demanding that the reader go to the next chapter or section.

Readers know many challenges await and that other crises will erupt before there is any final outcome or denouement. And if there’s no final outcome or denouement at the very end, well, perhaps the writer is hoping you’ll get the next volume in her series. Just kidding.

What are you reading? What films do you watch again and again? What are you streaming? What television series have you been watching? What video games or role-playing computer games stay in your mind?

Now apply the elements of plot (according to the words you prefer) to something you know well. Analyze how well any episode in the plot you’re recalling follows the plot elements or — if it does not — why not?

Post-Script on Plot

In case you are still worried about plot – whether it comes first, whether you can outline it in advance, and how it fits with character – here are some plot lines that may bring a bit of levity to your day:

- “The last man on Earth sat alone in a room. There was a knock on the door,” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich.

- “Epitaph: He shouldn’t have fed it,” by Brian Herbert.

- “Dinosaurs return. Want their oil back,” by David Brin.

- Apparently, Ernest Hemingway won a bet for the best short story ever, only six words: “For Sale: Baby shoes, never worn.”

The rumor is that a plot can consist of any two words, a subject and a verb. Here, for example, are a pair of words you might combine to make a plot outline (or as I prefer to call it, episodes in a plot). Choose one from Column A and one from Column B. Imagine a plot based on the two words. Imagine a few episodes you’d want to develop your plot.

| COLUMN A | COLUMN B |

|---|---|

| he | decided |

| the jury | left |

| she | argued |

| they | cut |

| the students | pulled |

Each combination suggests a plot to me – at this point, not very exciting – but, still, a plot. And that leads us to the next (and final) section of this blog.

What Makes a Good Plot

You have lots to think about in terms of plot. Your effort might feel somewhat like playing pickleball (or badminton, tennis, even tug-of-war), back and forth between plot and character. As you get closer to something that feels, as Anne Lamott said, like “a sort of temporary destination,” put it to a few tests:

- Is your plot adjustable as characters or events change. . .or is it iron-clad? (Answer: You should be able to see quite a bit of wiggle-room in terms of plot and characters at this point.)

- Are you willing to allow characters to change as the plot develops? (Answer: Yes. In fact, you find this an exciting part of writing fiction.)

- Are you willing to allow the plot to change as the characters do something unexpected? (Ditto the answer to #2.)

- Can you imagine a hook at the beginning, perhaps after establishing some sort of status quo? (Answer: Yes, you already have a good idea how your characters will be jerked out of stasis.)

- Can you imagine enough tension in the book to keep the reader reading? Are the stakes high for your main character and, perhaps, other characters? (Answer: Yes. You know that the subject + verb of “she left” doesn’t carry very much tension; it doesn’t have high stakes. But you’ve thought about that plot and have elaborated on it, perhaps something like this: “She left the backdoor swinging within its battered frame, not caring how much noise she made nor who would chase her.”

- What episodes do you see in your plot? Pick one – perhaps the one clearest to you at this point. Do you see this episode developing from some kind of status quo, rising action, a crisis point, some falling action, maybe even some denouement? (Answer: Any episode and even the overall plot of fiction will have each of these parts in some form or another. In some episodes, the status quo may be invisible – the falling action or denouement of the previous episode, for example.)

- Does one episode seem to lead to the next? (Answer: Yes, you should begin to see a possible sequence in episodes. You might notice gaps where readers need an episode to understand what is happening. Or, perhaps, you might wonder if you have too many episodes to demonstrate a critical part of your plot.)

- As you consider episodes in your plot, do you also see an overall trajectory for your novel or story? In other words, are you also seeing stasis or status quo that runs through the whole plot? Perhaps it is something that a character is battling throughout, learning a little about herself with each episode? Or the status quo messes him up each time he encounters a crisis? (Answer: Yes, you should begin to see vestiges of the status quo at various points of the book, for example. Although it would be nice to plan for the first part of your story to be about status quo, the middle about a crisis that is resolved so that the involved character achieves some resolution by the end of the story. But, it probably isn’t possible to sustain stasis for the first third of the book and you probably wouldn’t want to put a hold on tension for that much of the book. Rising action will lead to a crisis which will be met, changing the status quo until the next rising action occurs. . . .)

- Do you visualize a final climax, more engaging, fulfilling, and exciting that the previous climaxes? (Answer: You will probably see yourself building to that big climax at the end. You may not have thought of it, yet, but it will become clear to you as you develop each episode.)

- Are there any sub-plots in your book as you visualize it now? (Answer: These often emerge from how characters develop in your story. It’s possible that the main character experiences an arc that could be called major and another one that could be called minor. A secondary character could engage in a sub-plot as well as play a role in the major plot. It’s nice if these relate in some way.)

- Have you thought enough about your main character (or characters) to know where the conflicts lie? (Answer: Perhaps not. The next blog “Courting Characters” will help you understand character conflicts.)