Jerry Lee Lewis was the first to record “Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Is In)” in 1967, backed by the Memphis Boys, but the song is probably better known as the 1968 hit recorded by The First Edition with Kenny Rogers on lead vocals.

Mickey Newbury wrote this psychedelic hard rock song which many people perceived as a warning about using LSD. Others heard in its lyrics the zeitgeist of the 60s: Vietnam, the existential angst of the time, alcoholism, drug addiction, and depression.

This blog is not about any of these perils. The song’s title, however, addresses questions many beginning writers have: Am I ready to write? How do I prepare for writing? What conditions lead to successful writing? What conditions should I set up so that I can be successful?

Just about everyone who has written anything (including me) has a recommendation for how to write. Many of the recommendations make sense, but a few are so idiosyncratic that they don’t apply across the board (which has an interesting etymology, see box below). A few others may have a deleterious effect on writing.

It’s hard to know which recommendation to adopt or adapt – often because their advocates are so vehement about them. . .and apparently successful because of them. Of course, you are more likely to model the conditions under which you write after those set up by an author you admire.

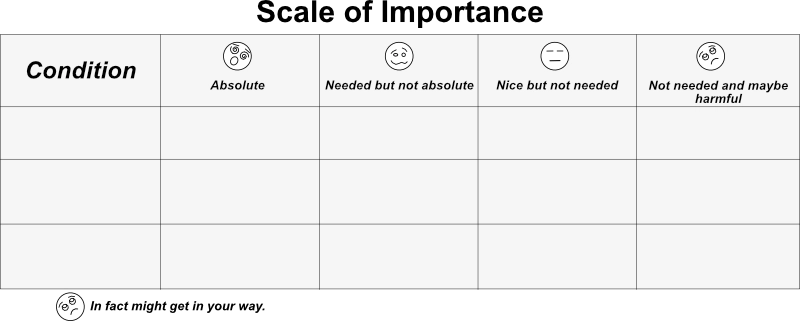

In the third blog, I introduced a Scale of Importance so you could evaluate recommendations about the conditions for writing for yourself:

Origin of “across the board.” According to Merriam-Webster, the phrase originated in the late 19th to the early 20th century in American horse racing. A horse that won across the board was victorious in all betting categories: winning, placing and showing.

I demonstrated how I would rate three conditions – and how other writers rated them – and explained my reasoning. The three conditions I discussed were daily writing for 45 minutes or more; preparing an outline to follow; and writing only what you know.

If you would like to do so, look at the following list of other conditions authors have proposed for successful writing. Where would you put them on the Scale of Importance?

The Much Ado 20 Conditions for Writing

- A regular place for writing.

- A productive routine. For example, “Read a masterful poem before you resume writing, even if you’re not writing poetry.”

- Enjoyment of writing; a preference for writing even when other activities are offered.

- Silence.

- Experience of perseverance in writing or other activities.

- Ability to learn new skills.

- A chair that is your “writing chair” – comfortable, providing the right height so that your feet touch the ground, and your elbows rise easily to the desk or tabletop.

- A clear desk or tabletop, except for your writing materials.

- Ability to see the whole as well as the details in something and make connections and find relationships in order to create the whole.

- Writing an entire first draft before revising and editing.

- Focusing on writing what you know. (Discussed in Blog #3)

- Enjoyment of reading; a preference for reading even when other activities are offered.

- Experiences with change, such as modifying something you’ve been building.

- Absence of people who might distract you.

- Having the mental and emotional energy to learn, focus and create

- Writing daily for at least 45 minutes a day. (Discussed in Blog #3)

- Revising and editing as you reread what you have written in your first draft.

- Reading what you have written aloud or to others.

- Having “A Room of My Own” (from an extended essay by Virginia Woolf). In other words, a place that nobody else uses. It’s all yours.

- Making an outline of what you want to write. (Discussed in Blog #3)

Note: The blog titles in bold are discussed in this blog.

I have thought about these and other conditions, adopted some, adapted some, and discarded others. I have also invented my own. Here are three conditions I rated Absolute and why, including comments by other authors. (I’ll discuss three more Absolute conditions I rated otherwise in my fifth blog and several conditions I rated in my sixth blog).

Some Absolute Conditions

Absolute #1: Enjoyment of writing (#3 above)

What would you do if you had two hours with nothing to do? Those who would choose to write are probably more inclined to become writers than those who would do anything but write. That makes sense, doesn’t it?

While we may not use a feathered pen and a bottle of ink, we are always ready to write. Writers are the ones who carry an index card or a tiny journal or notebook or – without other resources – scribble on a slip of paper (perhaps the back of a check) with a stubble of a pencil (or anything else that would make a mark) when they notice something interesting.

Some, like me, seldom write down what I notice (such as an anomaly – See my first blog post) right away, but I stow it away in my brain where it interferes with the rest of my thinking until I finally commit it to paper.

You can detect the writing impulse in children. They’re the ones who scribble something on a paper (or a wall or the refrigerator) and then grab an adult to listen to their story. The marks may not be alphabetic, but child knows that a swoop means duck, so she “reads” duck when she sees the swoop. Were you a writer as a child?

I waylaid visitors who came to our home so that I could tell them a story. These stories were imagined, but I told them with all the seriousness my three-year-old self could muster. When the visitors asked about some aspect of my story (such as did my mother really have wings), my mother realized 1) she didn’t want to curtail my enthusiasm for telling stories and 2) she wanted to give me a way to distinguish made-up from real stories. So she told me about “wink-wink.” At the end of an invented story, I had to say “wink-wink” to the listener so that he or she would not depart the house without ascertaining the truth about the subject of my story.

The only thing that saved me from embarrassment when I submitted my first story for publication in junior high was that I submitted it under a pseudonym. It was a maudlin advice column to “Dear Eve” from a thinly disguised equally maudlin me.

Stephen King describes being compelled to write as a child. His first stories were reconstructions of the comic books he read when he was sick at home. When he was 12, he sent his first manuscript to an editor who rejected it but projected a writing life for King and kept the story for posterity (and possibly to sell it at a very high price when King became famous).

In second grade, Anne Lamott was so moved by astronaut John Glenn that she wrote a poem about him that won a state award. She committed to being a writer when her teacher read her poem to her entire class. Lamott watched her father “who sat at his desk in the study all day and wrote books and articles about the places and people he had known.” (xii) She succumbed early to the creative impulse that Brenda Ueland writes about. Ueland wrote before she started school, before she submitted to a “world of unceasing, unkind, dinky, prissy criticalness” that nearly sneered her creative impulse out of her (xi). Many writers suffered similar situations when they went to school.

You may find that you have many other ways to use those two hours of freedom – besides writing. Some are necessary – an errand you need to run, a sick relative to call. Others are open to suggestion, and you may decide not to use them to capture an idea you have for an article or story. That’s OK, of course, but you might want to ask yourself if you have the condition of wanting to write. Forced writing isn’t particularly satisfying to the writer or those who read the writing.

Absolute #2: Experience of perseverance in writing and other tasks or activities (#10 above)

The Greek king Sisyphus may seem like the embodiment of perseverance. After all, he had to roll a huge boulder up a hill only to watch it roll back down just as it neared the top. He had to do this for eternity.

One difference between Sisyphus and most of us is that he had to do this chore because he had cheated death twice. He had betrayed Zeus who sent him to Hell, but he tricked Thanatos and – according to various myths – Ares or Hades – and did not die, at least not right away. It’s complicated.

Another difference is that Sisyphus’s task was both was both labor-intensive and futile.

It took a lot out of him to push that heavy rock up a hill with nothing to show for it at the end.

Writing may be hard work but it’s not Sisyphean because there is always something to show for it (if only a “grawlix” of @#$%&!* to represent swear words).

Most writers describe times they floundered and almost gave up or gave up momentarily. We don’t usually know about those who gave up entirely. Sometimes writers falter because of blockages. I’ll discuss getting stuck and unstuck in a later set of blogs. Until then, read what a few writers have said about floundering:

“This seems such a frightful task confronting you – to get this mass of material – amorphous and confused – into thin line sentences. (Brenda Uehler, 69)

“I’ll begin with the punch line: I’ve been putting off writing this essay. Writers write and writers procrastinate, but they do it in the opposite order.” (Julia Cameron, 223)

“There are few experiences as depressing as that anxious barren state known as writer’s block, where you sit staring at your blank page like a cadaver, feeling your mind congeal, feeling your talent run down your leg and into your sock.” (Anne Lamott, 17)

“Working doggedly on through crises like these, however, has always got me there in the end.” (Sarah Waters, Welsh novelist)

“At one moment I had none of this: at the next I had all of it. If there is any one thing I love about writing more than the rest, it’s that sudden flash of insight when you see how everything connects.” (Stephen King, 204)

Here’s an image that helps me persevere. Annie Dillard, an American writer known for her essays, prose, poetry, literary criticism, two novels and one memoir, introduced me to what I call the “honeybee approach.” In The Writing Life, she advises, “To find a honey tree, first catch a bee. Catch a bee when its legs are heavy with pollen; then it is ready for home.” (12) She describes how to catch the bee without harming it and then how to release and follow it. When you can’t follow it any longer, stop and catch another bee along the path. Repeat with any number of bees “until you see the final bee enter the tree.” You’ve gotten there, one bee at a time.

That’s how to persevere in writing, Dillard suggests: “So a book leads its writer.” She references Henry David Thoreau who professed the same belief.

Absolute #3: Ability to see the whole as well as the details in something and make connections and find relationships in order to create the whole.

This is a two-part condition, but both parts are related:

- Part One: Seeing the Whole and the Details;

- Part Two: Making Connections and Finding Relationships

Part One: Seeing the Whole and the Details

I knew the secret of George Seurat even before I saw his painting A Sunday on La Grande Jatte at the Art Institute of Chicago. I stayed as far away from it as I could to see the whole painting, and then I slowly moved closer, getting a different picture with each step. I wasn’t the only viewer doing this dance; others moved in parallel tracks closer to and then further away from the famous painting. At some point, I reached a turning point. The picture changed for me, and all I saw were dots of color. Backing up a step or two returned me to the scene of Parisians in Victorian dress enjoying a picnic on an island in the Seine. Forward again, and I took the picture with me in my mind as I studied the dots.

I imagine Seurat doing exactly this dance as he painted this and other pictures using a technique that warranted the name “pointillism.” The technique represented his belief that our minds can mix together what are dots or points of different colors (some complementary on the standard color wheel and, therefore, opposite, such as red and green; some analogous or next to each other on the wheel, such as red and orange). I also imagine Seurat and other pointillists such as Paul Signac and Camille Pizarro and neo-pointillists having to keep the whole in mind while close enough to the canvas to paint dots of the right color.

If you’ve ever been an inch or two away from an old color television or computer monitor, you have how technicians achieved color with dots that relied on the capability of viewers to blend those colors to get a believable image. The technique was known as RGB because it used the colors red, green, and blue to stimulate our minds to create all sorts of colors, such as purple, teal, orange, bronze, carmine, beige, olive, turquoise, periwinkle – or whatever the whole picture required.

Writers do something similar. They have some image of the whole – a theme or an idea, character, plot or situation, event, description, quotation or piece of dialogue – and, writing as fast as they can, using the tools at hand, they write with “dots,” which are words alone. These connect with other dots into phrases, sentences, paragraphs, perhaps whole sections of a piece of writing.

Then they step back and consider “fit.” (Remember Blog Post Three.) They ask of themselves, “Can I see the whole? Have the dots changed it in some way? Do I like how the whole has shifted? If not, which dots do I need to adjust or replace? If so, what implications do these new dots have for the whole – not only what I’ve done already but what I am doing next?”

I’ll get very specific with my own writing. The main character in Through the Five Genii Gate told me she wanted to emphasize what it was like to be a single American woman in 1937. Of course, she didn’t exactly grab me by the collar and yell in my face that I needed to add a scene in which she is accosted by a male who believed she couldn’t get herself out of danger without his help. I just knew I needed to write that scene.

The whole picture had changed and, not only did I need to add a new scene, I needed to adjust some of the “dots” before that scene and some afterwards. I kept the revamped whole in mind while I reread the parts and made the changes.

Once, I deleted several pages of writing when I realized I’d gotten the “dots” wrong. I liked what I’d written but, when I held it up to my concept of the whole, I saw that I had written a travelogue, not a novel. An enchanting place, but there was no action to move the story ahead. Scratch that.

Let’s go back to the condition. If you already notice the “whole” of something like a house or garden, and then detect a particularly errant or apt dot, your mind might already function whole-part-whole. I recall a beautiful stucco house in the desert, but I also recall a detail that forever spoilt that house for me – it had a tall tower on it, a turret really, that was more suitable to the green and rocky highlands of Scotland than to the dusty, flat land of Tucson.

What evidence do you have of your ability to see the whole as well as the details? Have you ever applied that ability to writing?

Part Two: Making Connections and Finding Relationships

The way we make sense of the parts is by making connections and finding relationships among them.

The way we make sense of the whole is by seeing the connections and relationships among the parts.

What Stephen King said earlier in this blog described making connections and finding relationships: “At one moment I had none of this: at the next I had all of it. If there is any one thing I love about writing more than the rest, it’s that sudden flash of insight when you see how everything connects.” (Stephen King, 204)

Everything connects. Indeed, that is magical. I call it the feng shui of writing. This Chinese phrase refers to a traditional practice for achieving harmony. The goal of the practice is to harmonize individuals within their environments (which are in harmony) and with other individuals seeking harmony within in their own environments.

I don’t think of this practice as scientific (although some do). I agree with King that it can be magical, but the magic comes about because of the work the writer does before, during and after writing a piece.

AltonThompson –

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:101.fountain.altonthompson.jpg

I learned the importance of this practice as a teacher, both of K-12 students and adults.

- Before teaching, I had to think about how my students related to each other and to me and to our topic. What were our connections? When could I help them learn something by working together? When could I help them learn something new by referencing something they already knew or could do?

- During teaching, I noticed what seemed off beam. What students were struggling? What was snagging them on a wayward branch while learning? What was I struggling with in terms of helping them learn? How could I make different connections or establish effective relationships both among students, with me, and with what they were trying to learn?

- After teaching, I analyzed students’ learning or lack of learning. What was amiss? Were they able to make connections between what they already knew and could do and what they were learning? Did they help each other learn? What could I do better?

I found my feng shui approach especially helpful when I planned workshops for adults. I liked for adults to teach themselves and each other. . .under my guidance. I usually debriefed the processes I was using with them before a break or lunch and adjusted them according to what I learned. I always evaluated the success of the workshop according to the degree of feng shui I noticed during the day. . . or somehow failed to establish.

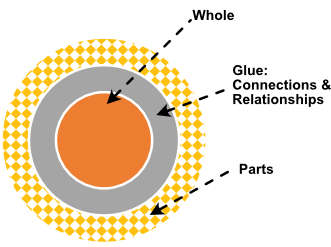

GLUE: That’s another way to look at the ability to see, create, and use connections and relationships to turn parts into a whole.

CONNECTIONS AND RELATIONSHIPS ARE THE GLUE THAT TURNS THE PARTS INTO A WHOLE.

A whole creation (solid orange in the center of this diagram) requires the creator to bond (the gray between the solid orange and the dots) multitudinous details (dots of orange in the outer ring), some closely related, some disparate. The creator can make a whole (such as a book about history) out of parts (names, dates, and events, for example) by connecting the parts and showing how they relate to each other and to the whole idea or thesis of the essay.

Here are examples of how I worked to create a whole out of many parts through making connections and establishing relationships in my novel Through the Five Genii Gate:

- Main Character: My main character is highly moral; she would not abandon her children to accompany an unknown man to safety. I connected her value to an action she refused to take.

- Plot/Situation: My main character’s quest is to make a difference in the world, so she “runs away” or escapes from situations that do not advance that goal. For example, she runs away from the little village of Ying Tak because the work she was doing there was exactly what she had done back in the States. That plot element did not connect (could not be glued) to anything else she was doing to achieve her goal, so she had to escape.\

- Theme: Although the countries are quite different, the power relationship between women and men in the United States and China at the time are similar, so I glued together incidents that demonstrated this relationship.

- Other Characters: The main character in my book has a strong connection with her children, especially her two daughters who escape China with her (her son has gone missing). For this reason, I have the main character tell part of the story in her own voice (first person), but another, equal, part of the narrative is third person and allows her daughters to tell the story.

In the first two examples, the connection or relationship is adverse to other parts and would not have contributed to the whole, so I had to resolve them. Conflict, adversity, tension – whatever you call it – is essential to keeping the reader engaged. When the stakes are high, the reader will keep flipping the pages until resolution (which can be through correction, elimination, addition, or some other action).

Imagine yourself mucking around in the orange dots, noticing which of them glue together nicely and contribute to the whole. Also notice the ones that aren’t behaving. As a writer, you can decide to let the conflict among them play out but – at some point – you’re going to have to bring them into line so they support the whole. You’re going to have to make the unruly ones connect or relate to each other and to the rest of your narrative.

I’ll discuss three more Absolute conditions I rated otherwise in my fifth blog and several conditions I rated otherwise in my sixth blog.