I discussed three conditions I consider absolute for success in writing in the previous blog, The Condition Your Conditions Are In:

- Absolute #1: Enjoyment of writing

- Absolute #2: Experience of perseverance in writing and other tasks or activities

- Absolute #3: Ability to see the whole as well as the details in something and make connections and find relationships in order to create the whole

- Part One: Seeing the Whole and the Details

- Part Two: Making Connections and Finding Relationships

As you consider that label – Absolute – in terms of the first three conditions in the previous blog and the three in this blog, please remember that you are in charge. Whatever I recommend – or another author recommends – may not fit for you. Consider the recommendations and adapt them to your circumstances and needs.

Here are three more conditions I think are Absolute (with the caveat above):

- Absolute #4: Enjoyment of reading; a preference for reading even when other activities are offered

- Absolute #5: Experiences with change, such as modifying something you’ve been building

- Willingness to Change

- One Writer’s Willingness to Change

- Absolute #6: Having the mental and emotional energy to learn, focus and create

Absolute #1: Enjoyment of reading; a preference for reading even when other activities are offered

Very few writers would admit to not being readers too – maybe first (before writing) and foremost (as important as, or more important than, writing). Here is what a few say:

First

“When still a child, make sure you read a lot of books. Spend more time doing this than anything else.” (British author Zadie Smith)

“I grew up around a father and mother who read every chance they got, who took us to the library every Thursday night to load up on books for the coming week. Most nights after dinner my father stretched out on the couch to read, while my mother sat with her book in the easy chair and the three of us kids each retired to our own private reading stations.” (American novelist and non-fiction writer Anne Lamott, xi)

“Long before I wrote stories, I listened for stories. Listening for them is something more acute than listening to them. I suppose it’s an early form of participation in what goes on. Listening children know stories are there. When their elders sit and begin, children are just waiting and hoping for one to come out. . . .” (Eudora Welty, American short story writer, novelist and photographer who wrote about the American South, 14)

“At that time, the cultural level and facilities of my country were so inadequate that I couldn’t buy books worth reading. There were not sufficient libraries. I used to think that the textbooks in schools were the only books that existed in the world. And then I entered high school, where I discovered a small library full of books. Though it was, as I recollect now, a very small and poor library, I thought of it then as a great Babel’s library. I read the World Literature Collections for the first time there. The writers who interested me most were the Russians – Dostoevsky and Tolstoy; the Britains – E. Bronte and T. Hardy; the French – Stendhal and V. Hugo; the Germans – Goethe and Schiller; and the Americans – N. Hawthorne and M. Twain. (Jeong Hanyong, a student in the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa)

“When I look back, I am so impressed again with the life-giving power of literature. If I were a young person today, trying to gain a sense of myself in the world, I would do that again by reading, just as I did when I was young.” (Maya Angelou, American memoirist, poet, and civil rights activist)

“There are perhaps no days of our childhood we lived so fully as those we spent with a favourite book.” (Marcel Proust, French novelist, literary critic, and essayist)

Foremost

“Books are the perfect entertainment: no commercials, no batteries, hours of enjoyment for each dollar spent. What I wonder is why everybody doesn’t carry a book around for those inevitable dead spots in life.” (Stephen King, American author of horror, supernatural, and fantasy books)

“Read, read, read. Read everything — trash, classics, good and bad, and see how they do it. Just like a carpenter who works as an apprentice and studies the master. Read! You’ll absorb it.” (William Faulkner, American novelist who set most of his books in Mississippi)

“I believe that reading and writing are the most nourishing forms of meditation anyone has so far found. By reading the writings of the most interesting minds in history, we meditate with our own minds and theirs as well. This to me is a miracle.” (Kurt Vonnegut, American writer and humorist known for his satirical and darkly humorous novels)

“Knowing you have something good to read before bed is among the most pleasurable of sensations.” (Dame Hilary Mary Mantel, a British writer whose work includes historical fiction, personal memoirs, and short stories)

“A reader lives a thousand lives before he [she] dies. The man [woman] who never reads lives only one.” (George R. R. Martin, also known as GRRM, an American novelist, screenwriter, television producer and short story writer)

“If you only read the books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking.” (Haruki Murakami, Japanese writer of novels, essays, and short stories that have been bestsellers in Japan and internationally)

“The beauty of literature is you allow readers to see things through other people’s eyes.” (Sandra Cisneros, an American writer best known for her first novel, The House on Mango Street, and a subsequent short story collection)

“I read to lose myself and find myself at the same time.” (Imani Danielle Mosley, a musicologist, cultural historian, and digital humanist and technologist focusing on the works of Benjamin Britten)

What’s Your Story of Reading as a Child?

The weekly trip to the library to get three (and only three books) was a treat for my mother, my siblings, and me. The library was our focus as we drove or walked down Main Street. At the west end of Main, it was a squat building of blond bricks. A wide set of gray cement stairs bound by iron railings led the way to the main level which had room-height arched windows. While I loved being in the light-filled main room, I was usually sent downstairs into the children’s section, lit by miniscule basement windows and hanging rectangular cages of industrial lights. It was dark but not scary.

I made my selection in a hurry, careful not to choose a book I had already read, and then raced upstairs to wait for everyone else, especially my mother who took her time to find enticing mysteries. We lined up by age behind mother to check out our books with our own library cards. The librarian, who usually sat at a bank-sized oak desk to dispense information, rose from her squeaky, wheeled oak chair and came to one of the two “check-out” stations at a long oak counter along the back wall. She greeted us personally and commented on the books we had chosen.

We clutched our books to our chests, went home, and quickly dispersed to our reading nooks, me to my bedroom where I spread myself diagonally on the bed. My mother had too much to do – dinner to fix, for example – so she waited to indulge a mystery until we had all gone to bed. When I peeked into the living room late at night, I saw her in her robe and slippers in a comfortable chair, a floor lamp tilted so that it lit up the pages, and a glass of wine on the table beside her and a cigarette turning into ash in a modern ceramic ashtray. She treated herself nearly every night to a sacrosanct ritual: a good book, wine, a cigarette, no one to pester her, and silence.

I gobbled up those books so fast that I was usually hungry that night – for more books – but I had to wait a week. In the meantime, I read everyone else’s books, including those my mother had checked out, which I began to enjoy.

It was no surprise, then, when one day I did not descend into the library’s basement. I stayed upstairs and browsed books in the adult section, careful to avoid being seen by my mother. At check-out the librarian took my books to stamp their due date on both the white card in the pocket (which she kept) and the slip of paper pasted on the pocket itself (to remind me when they were due). This time, however, she stopped before she had stamped my first choice, Forever Amber, and gestured to my mother.

She whispered to my mother, “Is it all right for her to check out this book?”

My mother looked at me, and I nodded my head. My mother said to the librarian, “I suspect she won’t enjoy it, but I have no issue with her reading any book she chooses.” Thus, I began my adult reading adventures.

Now I have at least two books going at the same time, usually quite different, one – perhaps – on my Kindle and the other paper- or hardback. I get anxious when my bullpen of books is nearly empty and warm-up – as a good manager does – by adding a few more from the library or online. I seldom keep books, giving them instead to be placed in local libraries or sold by the Library Association to benefit the libraries. But I always have a few of my favorites ready just in case. . .just in case. Oh, banish the thought!

I usually read very fast, two or three books a week, except when I’m analyzing the author’s techniques to enhance my own writing. I never read books that are related to what I’m writing, but, when I take a break from my own writing, I often go back to a book I’m reading to get refreshed and ready to write again.

Absolute #2: Experiences with change, such as modifying something you’ve been building.

“MURDER YOUR DARLINGS!”

This piece of harsh advice has been used by writers (and others) to signal writers and other artists to let go of even their finest creations.

Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch (1863-1944) is said to have been one of the first to have uttered this advice:

Whenever you feel an impulse to perpetrate a piece of exceptionally fine writing, obey it—whole-heartedly—and delete it before sending your manuscript to press. Murder your darlings.

Quiller-Couch was a British writer who published under the pseudonym Q. He was a prolific novelist but is remembered best for his literary criticism and monumental The Oxford Book of English Verse 1250-1900.

Another who used it is American novelist William Faulkner (1897-1962). More recently, Stephen King commented in his book, On Writing: “Try any goddam thing you like, no matter how boringly normal or outrageous. If it works, fine. If it doesn’t, toss it. Toss it even if you love it. Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch once said, ‘Murder your darlings,’ and he was right.”

Diana Athill, A British literary editor, novelist, and memoirist who worked with some of the greatest 20th century writers, softened the blow, somewhat: “You don’t always have to go so far as to murder your darlings – those turns of phrase or images of which you felt extra proud when they appeared on the page – but go back and look at them with a very beady eye. Almost always it turns out that they’d be better dead.”

Consider any artist in any medium. Imagine them examining a flawed, faulty, or defective piece of their work. Can you imagine any of them ignoring what doesn’t work? Can you imagine any of them choosing to let the flaw remain, even if it threatens the integrity of the whole? Can you imagine them choosing to spare “their darlings”?

Under what circumstances might they choose to keep the defective part (or whole)? This is actually a tricky question because some artists choose “deliberate imperfection.” According to blogger Austin Kleon, who is “an artist who draws,” and wrote Steal Like An Artist, “In Navajo culture, rug weavers would leave little imperfections along the borders in the shape of a line called ch’ihónít’i, which is translated into English as “spirit line” or “spirit pathway.” The Navajos believe that when weaving a rug, the weaver entwines part of her being into the cloth.” Other artists may repair imperfections or consider mistakes “happy accidents.”

So, this condition is less of WHAT you do and more about your WILLINGNESS to make changes and, even, “kill your darlings if necessary.” How do you feel about that?

Willingness to Change

Of course, it’s not just artists who encounter flaws. Imagine painting a room in your apartment or house. You run out of paint and, though you go back to the very place you bought it and page the salesperson who mixed and sold it to you, when you finish painting the room with the new paint, you notice that the colors are slightly off. What do you do?

One of the rose bushes refuses to grow and mars the hedge of roses you envisioned when you planted them at the same time, all in a row. What do you?

There’s no parking place in front of your building. What do you do? Do you give up and take the nearest one, several blocks away? Or do you drive around and around until one opens up?

Sometimes the effect of changing or not can lead to harmful or even dangerous consequences: you don’t have time to fix the spare tire; you decide not to pick up a prescription because you are running late; you decide your boss won’t read your report at 5:00 PM anyway, so you finish it overnight and have it on her desk before 8:00 AM.

How do you handle everyday challenges related to your everyday work? Do you resist making change to address the challenge? Do you acquiesce to the change in order to meet the challenge? What are your criteria for making a change? If you were to ballpark it, how many times out of 100 would you resist? Acquiesce? How would your resist/acquiesce percentage match those of people you know well? Those you admire? Those who are artists (writer or other media)?

BOTTOM LINE: How do you handle changes. . .of any kind? What are you likely to do when you are challenged (or challenge yourself) to change something you care about?

One Writer’s Willingness to Change

The best example I can use to illustrate how change (and even “murdering your darlings”) is part of writing is to tell my own story of writing Through the Five Genii Gate. I’ll let you imagine the “agony and ecstasy” of change. The “agony” is making change (and each situation ensures more than one change); the “ecstasy” part comes when you’ve made the change(s) and seen that it (they) works (work).

General Concept

Start: Biography (nonfiction)

Change: Added fictional bits and pieces to fill in gaps in my knowledge

Change: Went back to facts-only biography

Change: Converted to historical fiction (and rewrote many sections)

Change: Converted to biographical novel (and rewrote many sections)

Change: Converted to narrative nonfiction (and rewrote many sections)

Change: Converted creative nonfiction (and rewrote many sections)

Change: Rewrote entire book as a biographical novel (which it remains)

Main Character

Start: Entirely factual

Change: Added fictional bits and pieces to fill in gaps in my knowledge

Change: Made her an amalgam of various known characters

Change: Went back to a mostly factual character

Change: Allowed some parts of her character to be “likely”

Change: Took a big step by allowing the main character to challenge some of the known information about her (allowed her to be the opposite of what the facts decreed)

Change: Made character’s personality warmer than the facts warrant

Change: Reconsidered her factual goals and changed them according to my new understanding of her. Strengthened the goals to make the stakes higher.

Change: Created inner thoughts for her to express (based on my knowledge of the facts plus by invention of her)

Change: Depended on others’ likely reactions to her as a way to characterize her.

Change: Allowed her to be a character who is not always a “goody two-shoes”

Change: Allowed her to react to situations with both strengths and weaknesses

Change: Altered her name several times (once I decided my narrative would be a novel, I felt I needed pseudonyms for the main and secondary characters)

Other Characters

Start: From facts only

Change: Added characters who were likely there; created them as might have been

Change: Eliminated characters that were present but not needed to advance the narrative

Change: Reduced the role of characters who did not have much to contribute to my changed narrative

Change: Modified characters as they connected with each other and contributed to the whole – sometimes slightly, other times greatly

Change: Renamed characters who were present in the factual biography (except for famous, well-known ones such as Chou En-lai)

Change: Created names from the time period for my invented characters

Change: Developed back-stories for most invented characters, but did not use them in the book

Voice

Start: Entirely third person (I told the tale)

Change: Entirely first person (the main character tells the tale)

Change: Blended first person (main character narrates independent stories of her life) PLUS third person omniscient (me) who allows others to react to and speak to main character and also allows for context and transition

Note: I didn’t complete the book in first person; it didn’t work. Creating the book as a blend of first and third person required a total rewrite, though I borrowed from first and third person drafts.

Development

Start: Chronological

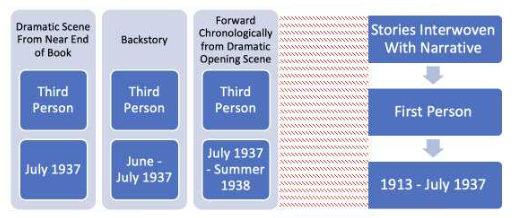

Change: In media res: started with dramatic first scene that I took from near the beginning book; then filled in some backstory; then continued chronologically from dramatic first scene

Change: In media res: started with dramatic first scene from near the ending; then told back story that led up to that scene; then moved the narrative forward but wove in stories that went back to the earliest events in my main character’s life up to the present day (1937)

Note: The way I decided to develop my narrative did not simplify things. In fact, by having two interwoven narrative arcs, I had to create elaborate color-coded timelines, and check them as often as a traveler checks flight delays.

Here is how I diagrammed my process:

Plot/Situations

Start: Biography = plot and situations

Change: Kept basic events from biography, but reduced, eliminated, augmented, rearranged some situations

Change: Made sure that situations were plausible through foreshadowing

Made sure that situations were connected to those before and after

Settings

Start: Included as they were in reality

Change: Reduced or eliminated when they contributed little to the development

Change: Augmented to seem realistic and believable

Change: Invented if they contributed to the development; were made as realistic and believable as possible

Themes/Meaning/Symbolism

Start: At first, simply a biography of a woman whose life was unusual

Change: Started thinking of her differently:

I greatly admired for her courage (especially combating lop-sided challenges (including misogyny) with skill, energy, ingenuity, and determination).

I was proud that she wanted to make a meaningful life for herself and make a difference for others.

She was a symbol of bravery, especially in the face of the unknown.

She was a symbol of putting family first.

Change: Examination of how I developed these themes

Change: Elaboration where suitable/natural

Change: Additions to narrative, where suitable/natural

Absolute #3: Having the mental and emotional energy to learn, focus and create.

If you have made it this far in this blog, I would say you have the mental and emotional energy to learn and focus. Even if you broke your reading into two or three segments. . .even if you re-read parts. . .I would say you have the mental energy to learn and focus. And write. Even if you despaired once or twice and thought to yourself, “I can never finish this” and then went back to finish it, you have the emotional energy to write. And write.

Karen E. Bender published an essay “If You Have These Traits You Might Be A Writer” on the website Literary Hub (https://lithub.com/if-you-have-these-traits-you-might-be-a-writer/). Consider each one, especially HSP, and decide if it applies to you.

As a writing student, Bender worked up the nerve to ask her professor if she “had it in me to become a writer? Did I possess that ineffable, mysterious force? Could he, a famous writer, tell me yes or no?” As a writing teacher, Bender gets the same questions from her students.

I’ve already written about many of these traits, such as loving language (through writing and reading). Though she is hesitant to name “talent” as a trait because it is “a reductive word, and in some ways a destructive one,” she does write about HSP, which means a Highly Sensitive Person. People who are HSP are likely to have the emotional traits necessary for writing, according to researchers Elaine Aron and Arthur Aron, writing in the mid-1990s, which is summarized at https://hsperson.com by Elaine Aron. They are likely to

Avoid violent movies or TV shows;

Be deeply moved by beauty;

Be overwhelmed by sensory stimuli;

Feel a need for downtime; and

Have a rich and complex inner life.

Elaine Aron includes a self-quiz on her site hsperson.com. Like Bender, I took the quiz myself. While not every characterization applied, many did (11 of 14) such as

- I seem to be aware of subtleties in my environment.

- I find myself needing to withdraw during busy days, into bed or into a darkened room or any place where I can have some privacy and relief from stimulation.

- Other people’s moods affect me.

- I have a rich, complex inner life.

- When people are uncomfortable in a physical environment, I tend to know what needs to be done to make it more comfortable (like changing the lighting or the seating).

Not all these conditions (and others I checked) are optimal in many situations, and there are some downsides to them. Highly sensitive people may be overwhelmed by deadlines and hectic schedules, others’ expectations, and things that appear to be failures. Aspects of writing in other words.

Bender writes, “for writing—this sort of heightened emotional and sensory sensitivity is important. It’s what attunes writers to the quality of sunlight at noon versus dusk, or the sound of honking cars in the rain or the feeling of a particular sadness. The feeling of being highly aware of the gorgeous stickiness of the world, and of the wildness within yourself, means writers are porous—to experience, to elements, to feeling. It’s what makes a writer want to grab the world and wrestle it onto the page.

Bender describes – no surprise, here – that writers need “openness to the imagination.” This means, especially for fiction writers, “faith in the lie.” Also “particular and relentless stubbornness.”

She writes, “Another important trait for a writer is the ability to delude oneself.” In everyday life, that trait doesn’t sound particularly positive, but in writing it is necessary to live with an uncertainty: “You may finish your novel or not, someone may publish your book or no one will, readers may like you book or hate it, or worse, ignore it.” Delusion may help you get your first word on a page, write sentences; revise, edit or even “murder your darlings.”

Based on my own experiences, I would add a few (mostly) mental traits:

- Curiosity

- A sense of order, organization, or sequence

- An understanding of cause and effect

- An interest in variety (of words, sentences, dialogue, characters, scenes, etc.)

- Knowledge of the conventions (grammar/usage, spelling, punctuation, etc.), when to obey them, and when not to

- Understanding your own voice

- Achieving fluency

- Knowing how to revise and edit.

Most of these will be subjects of future blogs.

Finally, lest you think writing is all fun and games, here is Anne Lamott in her book Bird by Bird worrying over another book she hopes will be published:

“So you rant and you cry, and then your writer friends call and commiserate. And they really do feel sick for you, and angry, and they know you feel like a wounded animal, a raging bull and they say the right things, that they love you and they love your book. . . .” (215)

“Try not to feel sorry for yourselves, I say, when you find the going lonely. You seem to want to write, so write.” (231)

And, now, to end on a positive note with Anne Lamott:

“When I suggest. . .that devotion and commitment will be their own reward, that in dedication to their craft, they will find solace and direction and wisdom and truth and pride, they look at first at me with great hostility. You might think I had just offered them membership in my embroidery club. They are angry people. This is why they write. So let me go further. There are a lot of us, some published, some not, who think the literary life is the loveliest possible, this life and reading and writing and corresponding. . . .It is spiritually invigorating. . .it is intellectually quickening. One can find in writing a perfect focus for life. It offers challenge and delight and agony and commitment.” (232)

In this blog and my previous blogs, I discussed what I consider the absolutes (or most important) conditions for writing. In the next blog I will discuss a few that are

Needed but Not Absolute Conditions

Nice but Not Needed Conditions

Not Needed and May Be Harmful Conditions