If you have read

BLOG POST THREE: READY. . .SET. . .WRITE and

BLOG POST FOUR: THE CONDITION YOUR CONDITION IS IN

BLOG POST FIVE: DROPPING IN (TO SEE WHAT CONDITION YOUR CONDITION IS IN)

you’ll recognize this list of conditions for successful writing espoused by one or more authors.

THE MUCH ADO TWENTY CONDITIONS FOR WRITING

Note: The conditions that are boldface are those discussed in this blog. The blogs that address other conditions are noted within parentheses after the condition.

- A regular place for writing.

- A productive routine. For example, “Read a masterful poem before you resume writing, even if you’re not writing poetry.”

- Enjoyment of writing; a preference for writing even when other activities are offered (Discussed in Blog Post Four)

- Silence.

- Experience of perseverance in writing or other activities. (Discussed in Blog Post Four)

- Ability to learn new skills.

- A chair that is your “writing chair” – comfortable, providing the right height so that your feet touch the ground, and your elbows rise easily to the desk or tabletop.

- A clear desk or tabletop, except for your writing materials.

- Ability to see the whole as well as the details in something and make connections and find relationships in order to create the whole. (Discussed in Blog Post Four)

- Writing an entire first draft before revising and editing.

- Focusing on writing what you know. (Discussed in Blog Post Three)

- Enjoyment of reading; a preference for reading even when other activities are offered. (Discussed in Blog Post Four)

- Experiences with change, such as modifying something you’ve been building. (Discussed in Blog Post Four)

- Absence of people who might distract you.

- Having the mental energy to learn, focus and create. (Discussed in Blog Post Four)

- Writing daily for at least 45 minutes a day. (Discussed in Blog Post Three)

- Revising and editing as you reread what you have written in your first draft.

- Reading what you have written aloud or to others.

- Having “A Room of One’s Own” (from an extended essay by Virginia Woolf). In other words, a place that nobody else uses. It’s all yours.

- Making an outline of what you want to write. (Discussed in Blog Post Three)

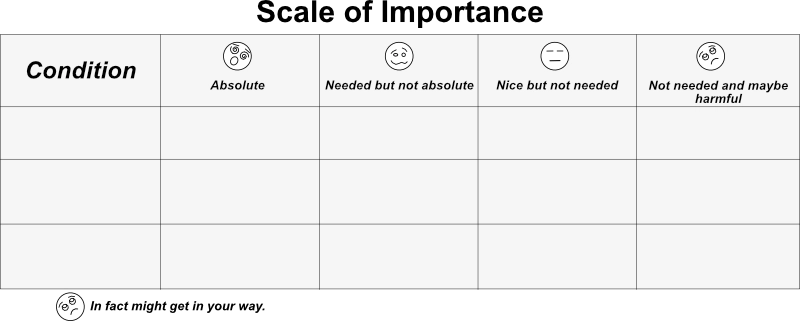

Scale of Importance

In my third blog post, I provided a chart so you could rank these conditions for your own particular writing needs. Here’s the chart:

Then I discussed rated and discussed three commonly cited conditions:

- Daily writing of at least 45 minutes a day (which I rated “Nice But Not Needed”)

- Use of an outline (which I rated “Not Needed and May Be Harmful”)

- Writing what you know (which I rated “Needed But Not Absolute”)

In my fourth blog I discussed three of the six.

CONDITIONS THAT ARE ABSOLUTE FOR SUCCESSFUL WRITING:

- Enjoyment of writing: A preference for writing even when other activities are offered.

- Experience of perseverance in writing and other tasks or activities.

- Ability to see the whole as well as the details in something and make connections and find relationships in order to create the whole.

In my fifth blog I discussed the remaining three of the six.

CONDITIONS THAT ARE ABSOLUTE FOR SUCCESSFUL WRITING:

- Enjoyment of reading; a preference for reading even when other activities are offered

- Experiences with change, such as modifying something you’ve been building

- Having the mental and emotional energy to learn, focus and create

That leaves the following:

SOME CONDITIONS THAT ARE NEEDED BUT NOT ABSOLUTE

- Silence (#4 in the Much Ado Twenty)

- Revising and editing as you write (#18)

- Reading what you have written aloud or to others (#19)

(I discussed writing what you know as needed but not absolute in my third blog post.)

SOME CONDITIONS THAT ARE NICE BUT NOT NEEDED

- A consistent time for writing every day (#17 in the Much Ado Twenty; discussed in my third blog post)

- A regular place for writing (#1)

- A productive routine (#2)

- A chair that is your “writing chair” (#7)

- A clear desk or tabletop, except for your writing materials (#8)

- Absence of people who might distract you (#14)

- Having “A Room of My Own” (#19)

(I discussed daily writing of at least 45 minutes a day, which is nice but not needed, in my third blog post.)

SOME CONDITIONS THAT MAY NOT BE PARTICULARLY HELPFUL

Writing an entire first draft before revising and editing (#11 above)

(I discussed writing an outline, which may not be particularly helpful, in my third blog post.)

I promise this blog post will not be as long as Blog Post Four. Also, as always, I invite you to let me know what you think about the conditions (Did I leave any out? Did I mis-state any? Should any be omitted?) and how you would have rated them. Send an email.

Many of these conditions concern space:

- A regular place for writing NICE BUT NOT NEEDED

- Silence NEEDED BUT NOT ABSOLUTE

- A chair that is your “writing chair” NICE BUT NOT NEEDED

- A clear desktop or tabletop NICE BUT NOT NEEDED

- Absence of people who may distract you NICE BUT NOT NEEDED

- Having “A Room of My Own” NICE BUT NOT NEEDED

Some concern time:

- Writing daily for at least 45 minutes a day NICE BUT NOT NEEDED

Some concern process:

- A productive routine NICE BUT NOT NEEDED

- Writing an entire first draft before revising and editing MAY NOT BE PARTICULARLY HELPFUL

- Revising and editing as you reread what you have written NEEDED BUT NOT ABSOLUTE

- Reading what you have written aloud to yourself or others NEEDED BUT NOT ABSOLUTE

I’ll group these to discuss them.

PLACE FOR WRITING

Writers vary immensely in terms of their preferences related to space. Think about these writers’ preferred places. Are they where you’d like to write?

Stephen King: “The space can be humble (probably should be, as I think I have already suggested), and it really needs only one thing: a door which you are willing to shut. The closed door is your way of telling the world and yourself that you mean business; you have made a serious commitment to write and intend to walk the walk as well as talk the talk.” (155)

Stephen King: “I also learned from Gould to ‘write with the door closed, rewrite with the door open.’” (57)

Annie Dillard: “When I flicked on my carrel light, there it all was: the bare room with the yellow cinder-block walls; a big, flattened venetian blind and my drawing [of the outside] taped to it; two or three quotations taped up on index cards; and on a far table some ever-changing books, the fielder’s mitt [a softball game was nearly the only thing likely to interrupt her writing time], and a yellow bag of chocolate-colored pens.” (30)

Julia Cameron: Multiple writing stations is a cheap trick. It keeps my writer from feeling cornered or like a child being sent to its room. Changing stations with my moods, I bribe myself into writing when I might not feel like it. I move stations to station some days, or write three days at a stretch at the picnic table, other times rotating briskly a station a day.” (210)

Julia Cameron: “Town. . .in longhand. . .library. . .coffee bars. . .bars. . .waiting rooms. . .hotel lobbies.” (210)

Julia Cameron: “I began my writing life in the upstairs corner bedroom of my parents’ house. It was a small room. The dresser, desk, and bed were painted white. The curtains, gingham, were lilac and white checked. (I write in a lilac room with white curtains today).” (119)

Stephen King: “The biggest aid to regular (Trollopian?) production is working in a serene atmosphere. It’s difficult for even the naturally productive writer to work in an environment where alarms and excursions are the rule rather than the exception.” (154)

Julia Cameron: “I remember Hunter Thompson saying to me, ‘The secret to good writing, Julia, lies in taking good notes. I take good notes.’ “’Taking good notes’ is another way of saying ‘place matters.’ When we place a piece of writing carefully and specifically (‘I am writing this on a sunny spring morning with sun streaming through white lace curtains and a lilac bush blooming against the window’), we create a context for what we are saying. We allow the reader to bring in a world of powerful associations and discriminations that makes the reader-writer dance far more intimate.” (119)

Stephen King: “. . .when it comes to writing, library carrels, park benches, and rented flats should be courts of last resort – Truman Capote said he did his best work in motel rooms, but he is an exception; most of us do our best in a place of our own.” (155)

Stephen King: Early in his writing career, King wrote in the“. . .laundry room of a doublewide trailer, pounding away on my wife’s portable Olivetti typewriter and balancing a child’s desk on my thighs.” (155) He mentions that John Cheever would “write in the basement of his Park Avenue apartment building, near the furnace.” (155)

Annie Dillard: “Appealing workplaces are to be avoided. One wants a room with no view, so imagination can meet memory in the dark. When I finished this study seven years ago, I pushed the long desk against a blank wall, so I could not see from either window. Once, fifteen years ago, I wrote in a cinder-block cell over a parking lot. It overlooked a tar-and-gravel roof. (26-7)

Which of these writing areas appeals and why?

Stephen King: “For years I dreamed of having the sort of massive oak slab that would dominate a room – no more child’s desk in a trailer laundry closet, no more cramped kneehole in a rented house. In 1981I got the one I wanted and placed it in the middle of a spacious, skylighted study (it’s a converted stable loft at the rear of the house). For six years I sat behind that desk either drunk or wrecked out of my mind, like a ship’s captain in charge of a voyage to nowhere. A year or two after I sobered up, I got rid of that monstrosity and put in a living-room suite where it had been, picking out the pieces and a nice Turkish rug with my wife’s help. In the early nineties, before they moved on to their own lives, my kids sometimes came up in the evening to watch a basketball game or a movie and eat pizza. They usually left a boxful of crusts behind when they moved on, but I didn’t care. They came, they seemed to enjoy being with me, and I know I enjoyed being with them. I got another desk – it’s homemade, beautiful, and half the size of the T. rex desk. I put it at the far west end of the office, in a corner under the eave. That eave is very much like the one I slept under in Durham, but there are no rats in the walls and no senile grandmother downstairs yelling for someone to feed Dick the horse. I’m sitting under it now. . . .”

Annie Dillard: “One afternoon I made a pen drawing of the window and the landscape it framed. I drew the window’s aluminum frame and steel hardware; I laid in the clouds, and the far hilltop with its ruined foundation and wandering cows. I outlined the parking lot and its tall row of mercury-vapor lights; I drew the cars, and the graveled rooftop foreground.” (28)

Annie Dillard: After being lured outside by a softball game which she spotted through her window and no writing, she “shut the blinds one day for good. I lowered the Venetian blinds and flattened the slats. Then, by lamplight, I taped my drawing to the closed blind. There, on the drawing, was the window’s view: cows, parking lot, hilltop, and sky. If I wanted a sense of the world, I could look at the stylized outline drawing. If I had possessed the skill, I would have painted, directly on the slats of the lowered blind, in meticulous colors, a trompe l’oeil mural view of all the blinds hid. Instead, I wrote it.” (29)

Lois Easton: I describe myself as a nomad. I move from place to place, sometimes whatever is available. I gave up my office with its door that opens and closes when my daughter went back to college. I now write at one end of a dining room that has no door to open and shut. To keep people out of my space and mostly quiet, I wrap accident-worthy yellow caution tape around the dining room table. I write at a modern teak roll-top desk, facing a window that looks out at a garden, pool, and bird feeders but can take/leave the view. My bookshelves have shrunk from eight sky-scraper tall white shelves to one-quarter of a bookshelf near my desk plus lots of boxes.

Virginia Woolf: “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” (5)

Alice Walker: “Virginia Woolf, in her book A Room of One’s Own, wrote that in order for a woman to write fiction she must have two things, certainly: a room of her own (with key and lock) and enough money to support herself. What then are we to make of Phillis Wheatley, a slave, who owned not even herself? This sickly, frail, Black girl who required a servant of her own at times—her health was so precarious—and who, had she been white, would have been easily considered the intellectual superior of all the women and most of the men in the society of her day.” (235)

PARAPHERNALIA FOR WRITING

Sometimes, as they describe their favorite places for writing, writers also discuss the paraphernalia, trappings, and just plain old stuff they need for writing:

Rita Mae Brown (an American feminist writer, best known for her coming-of-age novel Rubyfruit Jungle; these quotes are from Starting From Scratch: A Different Kind of Writer’s Manual): “Does this mean I compose at the computer? Not a chance. I need to hear the clack-clack of the typewriter and I dearly love yanking a splattered page off the roller. A computer removes these intense satisfactions from my day.” (51)

Julia Cameron: “For many writers, baroque music, particularly Bach, is what works. For writers, involved in long and complex pieces of logical writing, Mozart is said to actually raise and steady the I.Q. – as well as one’s math skills. The propulsive drumbeat of rock and roll drives some writers like a powerful engine. For other writers, the more evanescent and hypnotic effect of flute music sets them to musing.” (186)

Lois Easton: All I require, now, is a surface that’s clear except for a glass of water, my lap-top, and materials I will be using that day. If I’m skirmishing with thoughts or in the midst of a melee in my writing, I require silence. Otherwise, I can tune out voices, TV, and background noise; I seldom listen to music of any kind, especially if it contains lyrics, which lead me away from the words I’m writing. Outside light and the computer screen are enough for daytime, but at night I turn on the dining room light until its flickers annoy me, and I use an OttLite to focus on my desktop.

Stephen King: “If possible, there should be no telephone in your writing room, certainly no TV or videogames for you to fool around with. If there’s a window, draw the curtains or pull down the shades unless it looks out at a blank wall. For any writer, but for the beginning writer in particular, it’s wise to eliminate every possible distraction. If you continue to write, you will begin to filter out these distractions naturally, but at the start it’s best to try and take care of them before you write.” (156)

Rita Mae Brown: “You need good light. I spend hundreds of dollars on lighting in my workroom whenever I move. Right now I work with spotlights, five at 150 watts each, on a track over my head. Behind me, running like an L, are six more 150-watt spots and immediately over my typewriter is one of those fancy Italian lights that looks as though it belongs on a flying saucer.” (52)

Stephen King: “I work to loud music – hard-rock stuff like AC/DC, Guns ‘n’ Roses, and Metallica have always been particular favorites – but for me the music is just another way of shutting the door. It surrounds me, keeps the mundane world out. When you write, you want to get rid of the world, do you not? Of course you do. When you’re writing, you’re creating your own worlds.” (156

Rita Mae Brown: “Lastly, you need one cat, although two are better. Cats keep you from taking yourself too seriously. They are also good judges of literature. If a cat won’t sit on a freshly typed page, it’s not worth much. Think of your cat as the original muse.” (54)

Shari Lapena (a Canadian writer of thrillers, interviewed by Elizabeth Egan in Inside the List, a regular column in the New York Times Book Review, Sunday, August 27, 2023, p. 24): Egan: “Here’s a bit of writing advice you won’t hear very often: Get a cat. Sure, a slobbery mutt might turn out to be your new best friend, but a steadfast feline has the potential to be a muse. Lapena: “I have put her in my acknowledgments for every book that I’ve written.” Egan: “In her latest best seller, ‘Everyone Here is Lying,’ the former lawyer and English teacher writes, ‘And finally, thanks to my family, even Poppy the cat, who seems to have retired and doesn’t join me in the office anymore. . . .In ‘The End of Her,’ which came out in 2020, Lapena took appreciation for Poppy to another level, declaring, ‘I couldn’t do this without you.’”

Rita Mae Brown: “You need a good dictionary. Make that a great dictionary. The price of the Oxford English Dictionary, thirteen volumes, is $900 [around 1989]. When I bought my set they cost about $600. There is an OED compact edition with a magnifying glass that sells for $175. You can’t place a value on the OED.” Here are some other resources Brown keeps at her writing desk:

The Basic Book of Synonyms and Antonyms

Concise Dictionary of Quotations

Dictionary of Surnames

Dictionary of Literary Terms

Roget’s II: the New Thesaurus

The World Almanac and Book of Facts

The Elements of Style

Listening to America: An Illustrated History of Words and Phrases from Our Lively and Splendid Past

Lois Easton: I have gotten so dependent on Wikipedia and other internet sources that I keep only two books nearby: Roget’s and The Elements of Style. I donate to Wikipedia regularly.

TIME FOR WRITING

I discussed time for writing in my third blog when I responded to an injunction I have often heard (although the minutes may vary): Write daily for at least 45 minutes a day.

Here is my rating: Nice But Not Needed.

Here’s a summary of the points I made:

- Daily is good, if we can do it, but life gets in the way. Let’s not be too hard on ourselves.

- What’s sacrosanct about minutes? What other units could we use? Perhaps number of words? Or number of pages?

- What’s magical about 45 minutes a day? Or 3,000 words? Or five pages?

- Some authors describe the time they spend writing in terms of how long it takes them to finish the first draft of a book. What’s sacrosanct about finishing a first draft of a book in a year? Or ten years?

I confess that I don’t write daily, at least not physically, but I am always writing in my mind. As you might have noticed in my second blog, I am always writing in my mind, so when I sit down to write, my words decant onto the page without effort.

I write whenever (daily or every other day or twice a week) for as long as it takes for me to pour out what I hope will develop into a drinkable wine (to continue the metaphor). Sometimes several hours, sometimes a whole day. If it’s time to write. . . it’s time to write, as long as it takes me, and I can be insufferable until I’m finished. Just ask my family.

Consider your own way of handling time for writing:

Frequency:

___ daily___other: (describe) _____________________________________

Unit of Measurement:

___ minutes or ___words or ___pages or other: (describe) ________________________________

Achievement:

How often you achieve your schedule: ____ 100% of the time ___ of the time.

Get some insight into the time you spend writing by considering the following questions (which have no wrong or right answers but are intended to be provocative):

- What do you think about how often you write? Does that amount of time work for you?

- What do you think about how much writing you expect (minutes, words, pages, for example)? Does that expectation work for you?

- How often do you meet your goals for frequency of writing and output? Is this percentage just about right for you now? Could it be better?

- Do you think you have started to write something you would like to pursue?

- Do you have something you think you have finished in some way?

- When you don’t write, are you hiding behind a fear of not having anything to say? Or not being good enough? Or some other blockage? What might be blocking you?

- Are you ready and eager to write as scheduled? Are you disappointed whenever you can’t write as scheduled?

- Do you try to capture in a note what you would have written if you could have written as scheduled?

- What kind of schedule for writing would be more workable for you than your current schedule?

- What if you let yourself write when you felt like it? What would happen?

WRITING PROCESS

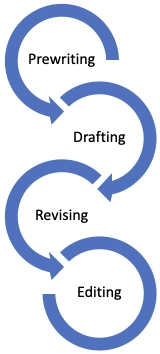

Most writing teachers and many writers believe in a writing process that has three or four parts to it:

Here is what these process steps usually mean:

Prewriting: Getting ready to write by conceptualizing or thinking about what you are going to write. Researching or otherwise gaining information about what you’re going to write. Scribbling some notes to yourself. Creating an outline (see BLOG NUMBER THREE for cautions about this). Trying out your ideas with others.

Drafting: Getting some words on paper (or on a computer screen). Trying out your concepts or ideas. In my seventh blog, I’ll give you some strategies for drafting, especially starting a first draft. Generally, you will write numerous drafts of any part of the whole creation (words, sentences, paragraphs, sections, chapters, etc.). Also, you may write several drafts of the whole creation.

Revising: Many people confuse revising and editing and both with proofreading and copyediting. Revising means “seeing again.” It suggests taking a good, hard – even critical – look at what you’ve written. It means addressing the big aspects of a piece of writing, such as

- purpose (and accomplishment of purpose)

- content (that is needed or should be deleted)

- strengthening content

- organization of content

- strength of support for content (details and specificity)

- style or voice

- clarity and readability

Often, revision is not only seeing again; it leads to writing again.

Editing: Revisions mean revising once more (at least). In other words, writers generally review their revisions to be sure they’ve accomplished what they wanted to during the revision process, such as strength and organization of content, appropriate details and level of specificity, style, voice, clarity, and readability. And, maybe, editing a revision will lead to another rewrite. And, then the second rewrite must be reviewed according to the elements of revision. Imagine a turnstile or a revolving door. Sometimes, that’s what revision feels like.

Generally, writers and those who work with them, such as editors, agree that there’s little point to editing or proofreading until the writer is reasonably content with the final revision – although, please note, some writers edit as they revise. Some even revise and edit as they write. I am one.

Editing means paying attention to the conventions of language, such as spelling, capitalization, punctuation, usage rules (such as parallel structure, subject-verb agreement, use of conjunctions and prepositions, appropriate verb tense, etc.). Editing gives a writer another chance to examine revisions to make sure they work in terms of the “bigger” things, such as style, tone, clarity, readability.

Proofreading is the final review of a piece of writing before sending it to a reader or publishing it. The words proofreading and copyediting are sometimes used interchangeably.

Here are some thoughts on conditions that make the writing process successful, three of which I have combined into one heading:

- A productive routine

- Reading, revising and editing

- Writing an entire first draft before revising and editing

- Revising and editing as you reread what you have written

- Reading what you have written aloud to yourself or others

ROUTINES AND RITUALS

Julia Cameron: “Much ado is frequently made about writers and their rituals. Writing, so the stories go, takes total concentration, a mustering of all intellectual energies – that and more. Special pens. Special notebooks. The desk clear and in perfect order. The phone off. The family backed off or somehow corralled. Privacy, even sanctity, is demanded. The writing process becomes a sanctum sanctorum.” (99)

Brenda Ueland: “I have found that playing the piano is a wonderful thing for it [getting the creative thoughts to come].” (45)

Annie Dillard: “Wallace Stevens in his forties, living in Hartford, Connecticut, hewed to a productive routine. . .rose at six. . .read for two hours. . .walked another hour. . .walked for another hour [at lunch]. . .walked home. Like Stevens, Osip Mandelstam composed poetry on the hoof. So did Dante. Nietzsche, like Emerson, took two long walks a day. ‘When my creative energy flowed most freely, my muscular activity was always greatest. . . .I might often have been seen dancing; I used to walk through the hills for seven or eight hours on end without a hint of fatigue; I slept well, laughed a good deal – I was perfectly vigorous and patient.’ On the other hand, A. E. Housman, almost predictably, maintained, ‘I have seldom written poetry unless I was rather out of health.” (33-4)

Brenda Ueland: “So you see the imagination needs moodling – long, inefficient, happy idling, dawdling and pattering. These people who are always briskly doing something and as busy as waltzing mice, they have little, sharp, staccato ideas. . . .but they have no slow, big ideas.” (32)

Julia Cameron: I use something called “the sandwich call. When I feel like I just can’t write, I pick up the phone and call X, Y, Z, A, B, C or Alex. ‘Stick me in the prayer pot,’ I tell them. ‘I don’t feel like writing, but I’m going to. I’ll call you when I’m done.’ After that call, I fill my time with writing. That done, I phone back and make the second half of the sandwich. ‘Thanks for the support. I’ve lived to write another day.” (210)

Brenda Ueland: “I learned that you should feel when writing, not like Lord Byron on a mountain top, but like a child stringing beads in kindergarten – happy, absorbed and quietly putting one bead on after another.” (50)

Reading, Revising, and Editing

Many writers advise against revising and editing while writing:

Will Self (an English writer, journalist, political commentator and broadcaster): “Don’t look back until you’ve written an entire draft, just begin each day from the last sentence you wrote the preceding day.”

Zadie Smith: “Leave a decent space of time between writing something and editing it.”

Annie Dillard: “The reason not to perfect a work as it progresses is that, concomitantly, original work fashions a form the true shape of which it discovers only as it proceeds, so the early strokes are useless, however fine their sheen. Only when a paragraph’s role in the context of the whole work is clear can the envisioning writer direct its complexity of detail to strengthen the work’s end.” (16)

Stephen King: “Kurt Vonnegut, for example, [rewrote] each page of his novels until he got them exactly the way he wanted them.” (209)

Stephen King: “Resist temptation. If you don’t, you’ll very likely decide you didn’t do as well on that passage as you thought and you’d better retool it on the spot. That is bad.” (211-2)

Julia Cameron: “The danger of writing and rewriting at the same time was that it was tied in to my mood. . . This made writing a roller coaster of judgment and indictment: guilty or innocent, good or bad, off with its head or allowed to go scot-free. I wanted a saner, less extreme way to write than this. I wanted emotional sobriety in my writing. . . .Aiming for that, I learned to write setting judgment aside and save polish for later. I called this new, freer writing ‘laying track.’ For the first time I gave myself emotional permission to do rough drafts and for those rough drafts to be, well, rough.” (19)

Lois Easton: “I am compulsive, and I admit it. I always reread a sentence, paragraph, whole page or more before I begin to write again. And, as I read it, I make changes: revision if I see something really wrong (like organization, style, characterization) and editing if I see a minor mistake in spelling, usage, punctuation, etc. Sometimes revising is vital to my next steps. I do not dare go on when a problem waves at me and shouts ‘help.’ Why should I continue something that does not appear to be working? I don’t have to catch and correct usage mistakes or misspellings but, well, if I see ‘em, why not get ‘em?” My process is not linear. I don’t finish one step and go on to the next: prewriting > writing/drafting > revision > editing. My process is recursive. It looks like this:

My voice is a giveaway if something is not working. I’ll read to myself and listen for the times when I become uncomfortable, when the words do not flow, when I am hesitating. Reading aloud to someone else (who apparently lost some lottery somewhere) is even more telling. I stumble, stop, and explain to my listener what I meant to write.

Advice You Can Enjoy

A good way to end this collection of blogs (1-6) is with a little humor. These are published nearly everywhere, sometimes in scholarly texts, manuals, and guides; as often on coffee cups, and tea towels.

How to Write Good

- Avoid alliteration. Always.

- Prepositions are not good words to end sentences with.

- Avoid cliches like the plague.

- Don’t be redundant; don’t use more words than necessary; don’t make each new paragraph highly superfluous.

- Comparisons are as bad as cliches.

- Utilize the patois.

- Be more or less specific.

- Never generalize.

- Eschew ampersands & abbreviations, etc.

- Parenthetical remarks (however relevant) are unnecessary.

- Be consistent.

- It is wrong to ever split an infinitive.

- Who needs rhetorical questions?

- Contractions aren’t necessary.

- Exaggeration is a billion times worse than understatement.

(some of these are from https://www.plainlanguage.gov/resources/humor/how-to-write-good/)

A Partial Bibliography

Brown, Rita Mae (1988). Starting from Scratch: A Different Kind of Writers’ Manual. New York: Bantam Books.

Cameron, Julia (1998). The Right to Write: An Invitation and Initiation into the Writing Life. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/ Putnam.

Dillard, Annie (1989). The Writing Life. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers.

Duncan, Lois (1979). How to Write and Sell Your Personal Experiences. Cincinnati, OH: Writer’s Digest Books.

Ferrante, Elena. (2016). Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey. New York: Europa Editions.

Hale, Constance (1999). Sin and Syntax: How to Craft Wickedly Effective Prose. New York: Broadway Books.

King, Stephen (2000). On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. New York: Scribner.

Lamott, Anne (1994). Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life. New York: Anchor Books.

MacNeil, Robert; Robert McCrum, and William Cran (1986). The Story of English. New York: Viking.

MacNeil, Robert (1990). Wordstruck. New York: Penguin Books.

Roget, Peter Mark (1941). Thesaurus of Words and Phrases. New York: Grosset & Dunlap.

Strunk, William B. and E. B. White (1959). The Elements of Style. New York: The MacMillan Company.

Ueland, Brenda (1987). If You Want to Write. Saint Paul, MN: Graywolf Press.

Walker, Alice (2004). In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Welty, Eudora (1983). One Writer’s Beginnings. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Woolf, Virginia (1935) [1929]. A Room of One’s Own. London: Hogarth Press.