The song “Stuck in the Middle with You” by Stealers Wheel is stuck in my mind, an agreeable kind of earworm. The part that crawls around in my head is the refrain: Clowns to the left of me/Jokers to the right/Here I am stuck in the middle with you. The part I pay attention to when I’m writing is I’ve got the feeling that something ain’t right/I’m so scared in case I fall off my chair/And I’m wondering how I’ll get down the stairs. That’s how I feel when I’m stuck somewhere in the middle of my writing and can’t figure out how to get unstuck.

If you haven’t yet been stuck somewhere in your own writing, you probably will be. The feeling is universal among creative people such as writers. This blog is about what it’s like to get stuck – or blocked – and how to get unstuck – or unblocked.

P.S. Thanks to Stealers Wheel for their lyrics.

What Does Getting Stuck or Blocked Mean?

Another line in the Stealers Wheel song resonates with me as a blocked writer: Trying to make some sense of it all/But I can see it makes no sense at all. That’s how it feels to hit writer’s block or get stuck. One of my favorite authors, Annie Dillard (American author, best known for her narrative prose in both fiction and nonfiction, including The Writing Life )wrote, “When you are stuck in a book; when you are well into writing it, and know what comes next, and yet cannot go on; when every morning for a week or a month you enter its room and turn your back on it” – that’s being blocked or stuck (p. 9).

It’s often a physical feeling. I get uneasy, jittery, nervous. I need to get up from my desk and move. I feel a little nauseated. It’s an emotional time during which I wonder if I’m supposed to be writing or supposed to be writing this. I fear I cannot accomplish what I’ve set out for myself, and I’m going to be sad, sorry, humiliated, and exposed. It’s mental trauma at its highest. I cannot think. I cannot remember what I was trying to do. I have no plan for accomplishing my goals. I have a problem, sometimes undefinable, that I don’t see clearly, never mind seeking a solution.

Who Else Gets Stuck?

Let’s assay getting stuck. Here’s what some authors say about becoming blocked; also notice what others say about these authors. Prepare for surprises and lessons learned that may help you. (You’ll find a list of sources at the end of this section.)

Known for Getting Stuck

These are authors who have admitted to getting stuck.

Ralph Ellison was going to write a follow-up to his amazing book, 1952’s Invisible Man, but he had “thousands of pages” and a “natural writer’s block as big as the Ritz and as stubborn as a grease spot on a gabardine suit.” There was no second novel until a friend used the pages to create the book Juneteenth after Ellison had died. A critic called Ellison’s form of writer’s block “productive. . . .It more closely resembled ‘chronic procrastination’”(#3).

Harper Lee (American writer of To Kill a Mockingbird, published in 1960, and much later a “sequel of sorts,” Go Set a Watchman, published in 2015). After Mockingbird was published, she claimed that the pressure and publicity of publishing was too much for her. That was, perhaps, an excuse because soon after Mockingbird’s publication she said, “I’ve found I can’t write … I have about 300 personal friends who keep dropping in for a cup of coffee. I’ve tried getting up at six, but then all the six o’clock risers congregate” (#1).

Vivian Gornick (American radical feminist critic, journalist, essayist, and memoirist) recalled, “I would look at the words on the page—still do—and think, This is so naive. This is so stupid. Who’s going to want to read this? How will I ever get another sentence out? Of course, every writer is vulnerable on that score. To the degree that you become a writer whose life is richly experienced through the work, you are, I believe, less tormented by that particular demon, and book by book the work will find itself deepening, paving the way for the very best a writer is capable of” (#2).

George R. R. Martin’s Winds of Winter, the sixth installment of his A Song of Ice and Fire series is still forthcoming. “Usually, after only two or three years between installments, this one is at least 12 years on the way and supposedly not even the final book,” Martin claimed at the Santa Fe International Film Festival in 2014, where he said that the delay has nothing to do with writer’s block but could be explained by distraction. He elaborated, “Because the books and the show are so popular I have interviews to do constantly. I have travel plans constantly. It’s like suddenly I get invited to travel to South Africa or Dubai, and who’s passing up a free trip to Dubai?” A fan wrote, “I think the problem is that he doesn’t actually want to write it — or even worse, he has no idea how to write it” and pleads for Martin’s publishers to let him go (#1).

Will Self (English writer of 11 novels, five collections of shorter fiction, three novellas, and nine collections of non-fiction) wrote, “You know that sickening feeling of inadequacy and over-exposure you feel when you look upon your own purpled prose? Relax into the awareness that this ghastly sensation will never, ever leave you, no matter how successful and publicly lauded you become. It is intrinsic to the real business of writing and should be cherished” (source unknown).

Mark Twain: “There are some books that refuse to be written. They stand their ground year after year and will not be persuaded. It isn’t because the book is not there and worth being written – it is only because the right form of the story does not present itself. There is only one right form for a story and, if you fail to find that form, the story will not tell itself” (#4). (Picture by A. F. Bradley; in the public domain)

Carson McCullers was terribly affected by not being able to write: She told William Goyen, “It was a murderous thing, a deathblow, that block. I just didn’t have anything to write. And really, it was as though I had never written. This happens to writers when there are dead spells. We die “ (#1).

Truman Capote: Martin Amis, himself an author, noted that Truman Capote (who wrote, among other books, In Cold Blood and Breakfast at Tiffany’s) intended his last work to be “a cutting, expansive takedown of high society,” but he spent the last 10 years of his life pretending to write a novel that was never there.” When it was published posthumously it consisted of “four pieces previously published” (#1).

Some Authors Get Stuck. . . But Easily Unstuck

Some authors have written about writer’s block as well as how they unblocked themselves. For example, in her 2017 documentary Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold, Joan Didion revealed that when she was stuck during the writing of The Year of Magical Thinking, she’d “put it in the freezer. . . .The manuscript, in the freezer, in a bag” (#1).

John Steinbeck (author of The Grapes of Wrath, Cannery Row, and so many other powerful novels) advised fellow authors to “forget the audience they were supposed to be writing for and, instead, [make] it more personal by writing to a single person. . . .This strategy helps remove the fear of writing to an unknown audience but it also, you will find, will give a sense of freedom and a lack of self consciousness” (#1).

In a 2001 speech, Ray Bradbury related that, when he “became blocked in his writing, he took it as a sign of being on the wrong track. In the middle of writing something you go blank and your mind says: ‘No, that’s it. You’re being warned, aren’t you? Your subconscious is saying ‘I don’t like you anymore. You’re writing about things I don’t give a damn for.’” “The cure for writer’s block is to “[stop] whatever you’re writing and [do] something else. You picked the wrong subject” (#1)

William Faulkner (author of As I Lay Dying, The Sound and the Fury, and Light in August) was entirely pragmatic about getting stuck: “The work never matches the dream of perfection the artist has to start with” (#4).

Stephen King (best-selling American author of horror, such as Carrie, The Shining, Pet Sematory, and most recently You Like It Darker; known as The King of Horror) writes that getting stuck may be the writer’s intention: “There may be a stretch of weeks or months when it doesn’t come at all; this is called writer’s block. Some writers in the throes of writer’s block think their muses have died, but I don’t think that happens often; I think what happens is that the writers themselves sow the edges of their clearing with poison bait to keep their muses away, often without knowing they are doing it” (#1).

Jhumpa Lahiri (a British-American author known for her short stories, novels, such as Unaccustomed Earth and Lowlands, and essays in English and, more recently, in Italian) commented that “’writer’s block’” is a “natural part of the creative process for almost all writers. There are times when one is bursting with ideas and inspiration and all the necessary components—time, focus, etc.—are in place. But there are other times when one or more of those elements is missing and writing is more difficult as a result. I have written for long enough to accept these patterns, and to understand that the blocks are temporary, that eventually, if one sticks to a schedule and tries to write on a regular basis, something will eventually come. I think a lot of what people refer to as ‘writer’s block’ is the period during which ideas gestate in the mind, when a story grows but isn’t necessarily being written in sentences on the page. But it’s all necessary, in the end. If I am feeling stuck or uninspired, I usually take a break and read. That always gets me going again” (#5).

Nora Ephron (American journalist, writer, and filmmaker) said in an interview:

“I am never completely cold. I don’t have writer’s block, really. I do have times when I can’t get the lead and that is the only part of the story that I have serious trouble with. I don’t write a word of the article until I have the lead. It just sets the whole tone – whole point of view. I know exactly where I am going as soon as I have the lead. That can take me three or four days and sometimes a week. But as for being cold – as a newspaper reporter you learn that no one tolerates you if you are cold; it’s one thing you are not allowed to be. It’s not professional. You have to turn the story in. There is no room for the artist” (#5).

Not Much Stock in Getting Stuck

Other writers are a bit skeptical about writer’s block.

Mark Helprin (author of Winter’s and A Soldier of the Great War) said in an interview: “Assuming that you are a professional and that you know how to write, why would you be unable to do so? If an electrician said, ‘I have electrician’s block. I just can’t bend conduit. I can’t! I can’t! I can’t run wires! Help me, please!’ he would be committed. One thing would be certain, and that is that his paralysis in the face of his work would have only to do with him, and not with his craft. I’m of the old school, I guess, and I would call writer’s block laziness, lack of imagination, inflated expectations, or having-spent-your-entire-advance-in-Rio-de-Janeiro-and-taking-taxis-and-going-to-restaurants-you-can’t-afford-before-you-have-written-a-single-word-of-the-book-you-pitched-to-a-cretin-with-an-out-of-control-cash-flow” (#5).

Terry Pratchett (English author, humorist, and satirist, best known for the Discworld series of 41 comic fantasy novels and the apocalyptic comedy novel Good Omens): “There’s no such thing as writer’s block. That was invented by people in California who couldn’t write” (#4)

Judy Blume (American writer of children’s, young adult, and adult fiction, including Forever and Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret): “I don’t believe in writer’s block. For me there’s no such thing as writer’s block—don’t even say writer’s block” (#5)

John McPhee (American writer who is one of the pioneers of creative nonfiction such as Basin and Range and Coming Into the Country. “The funny thing is that you get to a certain point and you can’t quit. Because I always worried: If you quit, you’ll quit again. The only way out was to go forward, to learn your way and write your way out of it” (#2).

Maya Angelou (American author, poet and civil rights activist, first famous for her book I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings) was “not fond of the term writer’s block, which she felt gave the phenomenon a power that she wasn’t comfortable with. But she did sometimes suffer from it and had a strategy for overcoming it: Just writing, even if what came out wasn’t her finest work.” “I may write for two weeks the cat sat on the mat, that is that, not a rat,” she said in Writers Dreaming. “And it might be just the most boring and awful stuff. But I try . . . .And then it’s as if the muse is convinced that I’m serious and says, ‘OK. OK. I’ll come’” (#3)

Sources:

#1 (from https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/65031/10-cases-extreme-writers-block)

#2 (from https://store.theparisreview.org/products/chapbook?variant=2250390994954)

#3 (from https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/654682/how-famous-authors-overcome-writers-block)

#4 (from https://darlingaxe.com/)

#5 (from https://lithub.com/is-it-real-25-famous-writers-on-writers-block/)

What surprised you about what these various authors wrote about writer’s block? What did you learn from them?

So You’re Stuck. What Do You Do First?

Annie Dillard (mentioned earlier) describes the first step blocked writers need to take: “Acknowledge, first, that you cannot do nothing” (p. 9).

I advise these immediate actions upon realizing you might be stuck:

- Thank the material for taking you as far as it has.

- Thank yourself for creating as much as you have.

- Make no decisions that cannot be unmade. Do not sell your computer, desk, chair or anything else that has helped you get as far as you’ve gotten. Burn nothing.

- Make no announcements of your utter failure to your family, friends, or the dog sitter.

- Apply for no jobs that involve hard physical labor, such as replacing the bridge over the Raging River.

- Breathe and keep breathing.

Hilary Mantel (British author, best known for Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies): “If you get stuck, get away from your desk. . . .Don’t just stick there scowling at the problem. But don’t make telephone calls or go to a party; if you do, other people’s words will pour in where your lost words should be.” (Quote from Goodreads).

Margaret Atwood (Canadian author best known for The Handmaid’s Tale): “Don’t sit down in the middle of the woods. If you’re lost in the plot or blocked, retrace your steps to where you went wrong. Then take the other road. And/or change the person. Change the tense. Change the opening page.” (https://lewislitjournal.wordpress.com/2012/12/17/writing-advice-change-it-up/).

Sarah Waters (Welsh author best known for novels set in Victorian society):“Don’t panic: Midway through writing a novel, I have regularly experienced moments of bowel-curdling terror, as I contemplate the drivel on the screen before me and see beyond it, in quick success, the derisive reviews, the friends’ embarrassment, the failing career, the dwindling income, the repossessed house, the divorce. . .” (https://chefnettie.com/dax-normans-weird-and-wobbly-animations-with-cigarettes-and-eyeballs-a-plenty/).

Annie Dillard: “Either the structure has forked, so the narrative, or the logic, has developed a hairline fracture that will shortly split it up the middle – or you are approaching a fatal mistake” (p. 9).

Learn more about getting stuck by reading Steven Pressfield’s well-known book, The War of Art: Break Through Your Blocks and Win Your Inner Creative Battles. He maintains that fear (often a reason for blockage) is ”good for the writing process – a writer should be afraid to face the blank page because it shows that he or she is taking his job seriously.”

Learn more about getting stuck by reading Steven Pressfield’s well-known book, The War of Art: Break Through Your Blocks and Win Your Inner Creative Battles. He maintains that fear (often a reason for blockage) is ”good for the writing process – a writer should be afraid to face the blank page because it shows that he or she is taking his job seriously.”

Getting Stuck May Be the Best Thing for You

When I first encountered the advice in this heading, I said something like “Hmph!” and looked in the freezer for chocolate ice cream. Julia Cameron (American teacher, artist, playwright, novelist, filmmaker, composer, journalist, best known for The Artist’s Way and The Right to Write) explained, “Although we seldom think of it this way, a writer’s block is often a very healthy self-protective response on the part of our inner creator to a dangerous threat” (p. 180).

Stephen King (best-selling American author of horror, such as Carrie, The Shining, Pet Sematory, and most recently You Like It Darker; he is known as The King of Horror) wrote about the benefits of being in a “creative jam.” “Boredom can be very good for someone in a creative jam. I spent those long walks being bored and thinking about my giant boondoggle of a manuscript” (p. 203)

Julia Cameron finally convinced me about the value of writer’s block: “Very often work dries up precisely because it was going so well. We have simply overfished our inner reservoir without having taken the time and care to consciously restock our storehouse of images” (p. 91).

What really persuaded me to keep writing no matter how I was feeling were these words from Cameron: “Writing is more comfortable than not writing. Writing is something more fun. Something more comfortable and more fun does not take ‘discipline.’ It takes permission, self-permission. I don’t write to be hard on myself. I write to be easy on myself. I write because it feels good” (p. 91).

Specific Sticker Shock

If you have the “Feeling that something ain’t right,” you may have Sticker Shock. The rest of this blog is for you. It is organized according to the various ways writers report being blocked, as well as how they have been able to unblock their writing. Again, thanks to Stealers Wheel for their lyrics.

Running Out of Ideas

If you worry about having something to write about, use a search engine to look up something you’re keen on and count the number of entries. Then think about what else could be written on this topic.

Let’s say I am researching women who do amazing things. One such woman is Mata Hari, so I wrote, “Did America have a Mata Hari?” The first thing I discovered is that that Mata Hari was not only “the famous dancer and femme fatale. . . a spy or merely an unlucky gossip” (https://time.com/4977634/mata-hari-true-history/) but also an American thoroughbred race horse.

I couldn’t count the horse named Mata Hari as an American version of Mata Hari, but to be sure of the answer to my question, I eliminated the horse entries and found about ten entries for each of ten pages. I figured that everything that had been written about Mata Hari had already been written, so I scrolled through the over 100 pages and found nothing about an American version of Mata Hari.

My answer to what else became, “I can write a comparison between Mata Hari and known American female spies. Fiction or nonfiction.” What would be your answer to one of your discoveries?

Recall Julia Cameron’s statement about writers needing to have an “inner pond of images.” She elaborates on this notion: “I have a drive to write and I do drive to write. I am very aware that the art of writing devours images and that if I am going to write deeply, frequently, and well, I must keep my inner pond of images very well stocked. When I want to restock my images, I get behind the wheels of my car” (p. 193). What else could you write about if, perish the thought, you couldn’t do anything with the piece that blocked you?

Nothing New to Write About

Adjacent to the fear that you’ll run out of ideas is that fear that what you want to write has already been written. Many times. By people who produced something far better than you’ll ever produce.

Writer Julia Cameron takes on this issue, too, in her book The Right to Write: An Invitation and Initiation to Into the Writing Life in a chapter called I Would Love to Write, But . .

She describes a conversation she had with a woman who tells her, “I am afraid of doing a lot of work only to have people say, ‘It’s been done before’” (p. 189). Julia’s response is “Don’t worry about being new. There is no ‘new.’ Worry about being human.”

When she asks her friend to “think over whether she herself demanded that the work she read [as a book editor] be wholly new,” she responded, “’Well, actually, no, when you put it that way,’”

Julia told her, “’I don’t think ‘new’ is what we connect to in writing. I think human is. . . . I think [what we write about is] whatever you are truly, humanly interested in’” (p.189).

“What’s human?” Julia asks. In Medium, an online magazine about compelling ideas, Marilyn Regan, comments, “Writing is about sharing our experiences and most of them are little. If we have to wait for something big to happen, some of us would have nothing to write about.” (https://writingcooperative.com/when-you-have-nothing-to-write-about-write-about-nothing-82134e428d6d

She continues, “So look at the day-to-day experiences, the routines, because it’s these things we have most in common: the commute to work, working through lunch, unreasonable bosses, looking forward to that ‘Happy Friday’ and the weekend.”

Look around your environment – yes, where you are right now. List what you think might be a topic you might use as the basis for writing a story or essay. Do it again, even though the process seems redundant: re-survey your environment and write down anything you did not consider in the first round as the basis for some writing. Perhaps these aspects of your environment seemed too common, too mundane, too shallow, or too uninteresting. Perhaps you thought, “Who would want to read about this?”

Now reconsider the items on your second list. Ask yourself, “What might be interesting about one of them?” Then ask yourself, “Could I write about this?” and “What might entice readers into what I have written?”

For example, consider this rather common picture. What might interest you about the ho-hum picture of a ho-hum item on this table?

Back to Julia Cameron whose book The Right to Write: An invitation and Initiation into the Writing Life by itself gives writers hope. She tells her writing class about making creative U-turns:

I told the story of how I’d begun as a short-story writer. . .when my best friend discouraged [me]. On a trip with my father, I said to him, “Pull over. Now.”

I grabbed for a notebook and began chasing the voice. My father nosed the little car deep into the Texas panhandle when I scribbled at his side. . . .We were doing a cool eighty but my hand was flying at the speed of light. I was quite literally driven to write. Before we pulled into a motel for the night, I had finished a short story. Twenty more would speed through my hand faster than my father’s car gobbled the white center line (p. 195).

She had made a U-turn literally and figuratively: “Driving kicks my writing engine. Driving lets me write full throttle. Driving drives me to the page” (p.195).

She’s not the only author who has found that driving recharges her ideas. “’Why is it,’ director Steven Spielberg once mused, ‘that I get my best ideas when I’m driving?’” (in Julia Cameron’s book, p.195)

For some outside help, return to Blog 7 “Your First Word Is Your Last.” This blog is all about strategies for getting ideas, such as

- Free Free Writing

- Selective Free Writing

- Mystery Free Writing

- Recursive Free Writing

- Last Word Free Writing

Or check out some of the online sites that provide prompts:

- I regularly receive prompts from Reedsy (prompts@reedsy.com). The most recent prompts were all about Heroes and Villains.

- Squibler, which has writing prompts according to category. (https://www.squibler.io/learn/writing/writing-prompts/writing-prompt-for-adults/

- PaperTrue also has writing prompts organized according to category. (https://www.papertrue.com/blog/writing-prompts/

You may not want to use exactly what results from these strategies, but perhaps the strategies themselves will point you towards something you want to write.

A Skirmish Between Expectations and Feelings of Inadequacy

We all have at least one image of WRITER, particularly a writer who has been published. Therefore, AUTHOR. When we can’t picture ourselves as writer or author; when we have no image of ourselves as writers/authors, we can encounter writer’s block.

Our self-esteem plummets. We may overthink. We may be hyper-critical. We are self-conscious. We think people will judge us harshly. We shut down whatever might expose us for who we really are (and that includes writing, especially if shared or published). We are afraid.

Perceived characteristics of authors can be daunting. We may doubt ourselves as writers, if we see writers and authors through the extreme lenses of ALWAYS, NATURALLY GIFTED, ADROIT, and NEVER DOUBTFUL ABOUT THEIR SKILLS.

I’M NOT! I CAN’T! THAT’S NOT ME, we scream aloud or silently when we are at our lowest. As you know from reading the section called Who Else Gets Stuck, we aren’t the only ones who have moments of doubt. Julia Cameron, whom you’re met earlier, comments:

Many people – ‘nonwriters’ if there is such a thing – think about writing a novel and imagine that in order to do it they must know everything before they start. No one could write a novel if that were the way it was done. And yet, unwittingly, ‘writers’ can make it sound like they did know, did plan, did think their books through in advance. I think this comes from a certain understandable human tendency on the part of writers to puff themselves up a little to make themselves seem a little more brilliant (p. 91).

It is my experience that tremendous and subtle image patterns are discovered after we write them, not planned out before. To the reader this looks like careful construction, what the books call ‘foreshadowing.’ Maybe for some writers, a blessed few, it is a conscious act, but for the most part I think such claims to creative consciousness are hooey. I think we’re just a little embarrassed to say, ‘Actually, that never consciously occurred to me. . . .’” (p. 71)

Wannabe authors have a whole lot of yabbuts, such as, “I’d love to be a writer, but I just don’t have the discipline.”

A real author – Julia Cameron – addresses that yabbut: “I know what they mean: neither do I. I am someone who has been writing ‘full-time’ now for thirty years. If I had to do it the way that people think it is done – with discipline – I am not sure that I would be able to do it at all” (p. 87).

But the truth is that I do love it and that I do not find it a discipline. I do not put in long hours at the keys – or very seldom. Instead, I snatch time. I write in the crannies of my life. I make my writing desk the most enticing corner – and sometimes corners – of my house. My desk has toys. My desk has flowers. My desk has pictures of my beloved daughter, Domenica, as a baby, and I do baby myself as I write (p. 87).

She worries about “People who write out of ‘discipline’” because they “are taking a substantial risk.”

They are setting up a situation against which they may one day strongly rebel. Writing from discipline invites extremism: ‘have to do this or I’m a failure.’ Writing from discipline creates a potential for emotional blackmail: “If I don’t write I’ve got no character” (p. 87).

People who write from discipline also take the risk of trying to write from the least open and imaginative part of themselves, the part of them that punches a time clock instead of taking flights of fancy. “Commitment” is a word I prefer to the word “discipline.” It is more proactive, more heart-centered, and ultimately more festive and productive (p.88).

Scrutinizing Self-Awareness Induces Fear

One of Julia Cameron’s students was stuck in a crisis of self-awareness. Asked to describe what was discouraging, this student “’read off a list of . . . ‘stuff,’ which sounded remarkably like my own ‘stuff’ – and like everyone’s – before heading into a piece of work. ‘I’m afraid I’m lousy.’ ‘I’m afraid I’m good but no one will think so.’ ‘I’m afraid this work won’t work.’ ‘I’m afraid this work will work but no one will see that.’ ‘I’m afraid I’m stupid.’ ‘I’m afraid. . . ” (p. 88).

Ultimately a crisis of self-awareness is about fear. Cameron writes, “’I’m afraid’ is always what stands between us and the page. When people talk about ‘discipline,’ they are really talking about ‘how do you get past ‘I’m afraid.’ The fears may not be conscious, and that’s what makes it tricky.”

She writes that our fear “may be disguised as our business or our ‘need to focus’ or any number of other distractions, but it boils down to our fear of revealing ourselves to others and ourselves” (p. 89). People look at her with amazement and say, “’So you don’t research?’ Not precisely, I focus on a certain situation, era, or locale and it’s as if I am tuned into a radio band. I meet people who know all about cartography if I am writing about maps. I set out to describe Magellan’s world and a young waiter brings me a copy of Magellan’s clerk’s diary. Out of the diary one detail will strike me – the clerk kept a secret stash of raisins which kept him from getting scurvy – and that detail will trigger a whole character, even a whole world.” (p. 72)

She’s asked, “’So you don’t plan what you write?’ I would say I dream it,” [Julia] replies. “It’s a sort of lucid dreaming where I carry the idea of the story and the Universe delivers to me bits and pieces as I need them.” (p. 72)

“Writing is a personal process. We can pick up tips and hints from each other, but at its base, writing is a solitary act. We all do it alone and we all do it differently” (p. 83).

My own experience is that somewhere around two thirds of the way through a piece I suddenly see what the writing was driving at. I see the patterns that have been set up and I get an idea where everything is heading. This point is a scary one. Now that ‘I’ know what ‘I’ am doing, I begin to worry that ‘I’ might not be able to pull it off. In other words, my ego wakes up. No longer content to let the writing write through me, it suddenly demands control. It wants this book to be ‘good.’ This is the point that I call ‘The Wall.’ All writers know it. The Wall is the point where a previously delightful project comes to a halt. The Wall is the point where doubt sets in. No longer writing for the sake of writing, no longer happy just to splash in the pool, suddenly we think about those other people in the pool with us, whether they are faster, better, stronger, showier. In short, we begin to compete, not just create” (p. 84). (Image by freepik)

“What can we do about this?” Pump ourselves up. Try to scale the wall (think about convicts trying to escape. “How did they successfully escape?” They burrowed under the wall. They crawled their way to freedom. This burrowing under the wall, this crawling, is what works to escape the prison of the ego. “So how do we crawl under the Wall?” Instead of “I’m great,” we say, “I am willing to write badly. I am willing to do the work to finish this project whether it is any good or not” (p. 74).

When we are willing to be humble, we wriggle our way under the Wall and back to the glee of writing freely. By willing to write “badly,” we free ourselves to write – and perhaps to write very well. In other words, we go back to sketching” (p. 75).

Fearing Perfectionism

You probably know someone who is a perfectionist, and you know that the fear is not about being a perfectionist. It’s about NOT being one.

Julia Cameron again: Writing doesn’t have to be prettied up. Writing doesn’t have to be perfect. Writing is about energy, about imperfection, about humanity. When writing gets to be a work in progress, when writing gets to be real “live’ rock and roll, then writing becomes infectious instead of disciplined. Writing becomes ‘Just do it’ and ‘Hey, let’s dance’” (p. 90)

Julia Cameron again: Writing doesn’t have to be prettied up. Writing doesn’t have to be perfect. Writing is about energy, about imperfection, about humanity. When writing gets to be a work in progress, when writing gets to be real “live’ rock and roll, then writing becomes infectious instead of disciplined. Writing becomes ‘Just do it’ and ‘Hey, let’s dance’” (p. 90)

I wear my writing like an old pair of Chinese silk pajamas. I like it loose and easy. My friend Alex suits up to write. He likes it structured. He goes to an office. What matters is that each of us must find our own writing style. Some of us are morning writers. Some of us write late at night. Some of us watch the clock. Some of us count pages. Some of us write in cafes. Others of us need quiet libraries. With luck and a little practice, you can have several writing styles depending on how you feel. The point is to get comfortable. The point is to be formal insofar as it serves you (91-2).

She notes, When it comes to writing, it’s OK to have a little tummy. It’s OK to write sentences with curves. It doesn’t have to be flat, hard, chiseled prose, the washboard prose they teach us in school. Writing as sit-ups. That’s what we can learn. Writing can be more comfortable than that. Writing can be earthy (p. 92).

I am a perfectionist, and it haunts me, almost daily, in various ways. You may have wondered why these blogs are so long (given the average length of a blog between 2 and 10 paragraphs). I unload on a subject and then remember something related. I can’t just discard what I’ve recalled. What if this one idea is exactly what the reader needs? And, that idea leads to one more and one more and one more.

Why do I create so few blogs? If you’d look at the size of each blog after the first two, you’ll understand how one more, etc., lengthens my work on each blog, even though I have other work to accomplish. I need to follow Julia’s notion and cultivate more tummy. No, no, no I don’t!

I have learned to recognize perfection and say, “Okay. I’m being a perfectionist again. What am I going to do about that?” Sometimes I actually do something and it works!

Julia Cameron reminded her students about the “Mel Brooks routine. . .’2,000-Year-Old Man,’ where the psychiatrist tells his patient, ‘Listen to your broccoli, and your broccoli will tell you how to eat it.’ And when I first tell my students this, they look at me as if things have clearly begun to deteriorate” (11).

Perfectionists often want control. They don’t trust just letting something go. They don’t trust intuition even though they may have very trrust-worthy intuition. Cameron writes that intuition means

of course, that when you don’t know what to do, when you don’t know whether your character would do this or that, you get quiet and try to hear that still small voice inside.

It will tell you what to do. The problem is that so many of us lost access to our broccoli when we were children. When we listened to our intuition when we were small and then told the grown-ups what we believed to be true, we were often either corrected, ridiculed, or punished (p. 110). (Image by Racool studio on Freepik)

LISTEN TO YOUR BROCCOLI!

Fearing Procrastination

We may procrastinate because we fear we secretly realize we cannot achieve perfection.

Online websites enumerate any number of reasons for procrastination. You can easily find a website on procrastination that you like, and you’ll discover reasons for your behavior, such as

- Fear of judgment or disapproval from others

- Fear of judgment or disapproval from within

- All or nothing thinking

- A need for control

- A family with unreasonably high expectations for themselves, including you

A little humor helps. Julia Cameron’s first thought about writing about procrastination was, “I’ll begin with the punch line: I’ve been putting off writing this essay. Writers write and writers procrastinate, but they do it in the opposite order” (p. 225).

She adds, At its root, procrastination is an investment in fantasy. We are waiting for that mysterious and wonderful moment when we are not really going to be able to write, we are going to be able to write perfectly. The minute we become willing to write imperfectly, we become able to write. It is helpful to ‘bust’ ourselves on this addiction to perfectionism. Instead of saying “I’m waiting until it feels right to write,” try saying instead. “Oh, I’m being a perfectionist again.” Then let yourself write—imperfectly. (p. 225)

Here are some reasons writers, in particular, may procrastinate (and some antidotes):

| Reasons Writers May Procrastinate | Antidotes to Those Reasons |

|---|---|

| They are waiting for the right or perfect idea. | Start writing, and the ideas will come. |

| They are afraid they'll write a bad story, novel, poem, or piece of nonfiction. | Try to write a bad story, novel, poem, or piece of nonfiction. |

| They are waiting for inspiration. | Inspiration will come as they write, even if they start out with something mundane. |

| If they write something good, they'll have to write something better the next time. | Writing keeps the ideas flowing; new ideas will leap from a page that has writing on it. |

| Writers need emotional connection to others. | It's more satisfying to hear congratulations for writing something than sympathy for procrastinating. |

| It's safe not to write. | It's probably less safe mentally to avoid something you really want to do. |

| Writers need something to do. | Writers can invent all kinds of activities instead of writing. |

| Writers may need excuses for avoiding social interaction because they need to stay home to write. | Writers can invent lots of other reasons for avoiding social interaction. |

| Writers need something to blame for being unproductive. | Writers can always write SOMETHING rather than whine about coming down with procrastination. |

| They think of writing the WHOLE THING, and that's just too much to contemplate. They don't have the courage. | All we need to do, according to Julie Cameron, is "have the courage to write the next right thing." |

Julie Cameron indicts our sense of writing as a process: Writers procrastinate as part of a writing ritual. Most writers do not want to learn how rapidly and easily they could actually write and so they circle the desk a few thousand times like dogs looking for a comfortable spot to lie down. The idea that in order to write they need simply start writing is not welcome news. Writers become addicted to procrastination. It gives them something to do, instead of writing: namely, they can hate themselves. A writer who is not writing is generally filled with self-loathing and self-recrimination (p. 224).

You can detour around the tendency for procrastination, however. For example, set up regular expectations for writing:

Make yourself write something/anything for 5 minutes a day. Your writing can be a to-do list for the day, a gratitude, a description of the sky. Write the words “I can’t write” over and over for five minutes. Note: Your brain may get bored with those words and tug you into something more interesting. If you discover that you can’t stop after 5 minutes, increase the time you spend, but be ready to go back to 5 minutes when you can’t write more.

Give your five-minute write an exotic name and say that name aloud to yourself or others daily. Try:

- I need to have some apricarol.

- I’m ready for a bit of trulimose.

- Ooops. Time for whimsaway.

Or use “regular” words that could describe writing:

- My earwig is calling.

- It’s marlarkey time.

- I haven’t made my brouhaha for the day.

Fearing Loneliness

Writers and other creative people are often labeled loners. It’s true that such people are often alone as they paint, score a symphony, practice their lines, or write, but they don’t have to feel or fear loneliness, which might make them put off their work (procrastinate).

I like being alone, up to a point, but I do sometimes encounter loneliness. I defang it by calling loneliness something else: the lonelies. It’s not genetic. It’s not a life-long impediment. I can call it what it is – I have the lonelies right now – and decide what to do about my condition.

Once again, the words of Julia Cameron help me: “. . . .we do not go into a room all alone. We go into a room that is crowded by our own experiences, jammed to the rafters with our thoughts, feelings, friendships, gains, and losses” (p. 77).

I do not write well when I am going through the lonelies. Julia Cameron acknowledges that she might be “lonely today because I did not write enough yesterday. Not writing, I drop the thread of my consciousness. I lose track of myself. It is me, my consciousness, that I’m missing. It is often disguised as missing someone else, and we do that too” (p. 77).

She wrote, “I would argue that the writing life is proof against loneliness. It is a balm for loneliness. It is an act of connection first to ourselves and then to others. . . letters are what we are writing, really. Letters to ourselves. Letters to the world” (pp. 77-8).

I wrote earlier in this blog about feeling uneasy when I’m experiencing writer’s block. Intuitively, I know something is wrong. Julia Cameron wrote, “When I don’t write enough, I get a gnawing sense of disease. It is an appetite that isn’t sated by other things. I become lonely for my soul. I try to find it by talking with people” (p. 78). She does everything but write to occupy herself but finally realizes, “oh, yes, I need to write. That’s what’s bothering me” (p. 79).

One cure for the lonelies or loneliness is friendship with someone who understands what being a writer means. Another is belonging to a formal or informal group of writers. I’m not very good at joining, participating, or helping myself or others in these ways. As a perfectionist, I sometimes worry too much about the other person or too much about the experiences in the group and do not attend to my own needs. Sometimes, however, I hear something that starts me down a new path of learning. Sometimes, I believe, I help others.

Sadly, almost always I return from a coffee or a writers’ group wishing I’d written instead. This might sound a little crazy (and who isn’t?) but sometimes I write a letter to a character, such as the main character in my novel Through the Five Genii Gate. Julia describes a letter that she wrote to Sam. I’m not sure if Sam is real or a character, but writing the letter helped her get what is bothering her, which she describes “as depressing as that anxious barren state known as writer’s block, where you sit staring at your blank page like a cadaver. Feeling your mind congeal, feeling your talent run down your leg and into your sock” (p. 176).

Fearing Critics and Not Publishing

As if fearing perfectionism, procrastination, and loneliness weren’t enough, we may also fear critics and not publishing.

Money

Let’s begin with money. I know it is not up there in the main heading of this section, but it may lie beneath both criticism and publishing.

Julia Cameron had a phone conversation with a woman (a former children’s book editor) who wanted to write. Julia asked this woman why she did not write: “Why really?”

The woman responded, “’Well, I guess I am scared of doing all that work for nothing. I mean, what if I write all my stories and no one buys them?’” (p. 190). Julia Cameron responds that she would have had the pleasure of having written them. She tried to convince the woman that the process of writing was, itself, worthwhile (p. 190).

She explained in her book The Right to Write, “For many of us, best-sellerdom is not even what we are after. We are after the joy of being read” (p. 191). Online publishing has grown the market for books in a gargantuan way. If not best-sellerdom or listed in the New York Times Book Review, how about knowing that people are reading free copies of your book online?

Another author, Brenda Ueland (a journalist, editor, writer, and teacher of writing) admits,

One great inhibition and obstacle to me was the thought: will it make money? But you find that if you are thinking of that all the time. . .you don’t make money because the work is. . . empty, dry, calculated, and without life in it. Or you do make money, and you are ashamed of your work. . . .Another great stumbling block and inhibition to me was the idea that writing (since I wanted to make a fortune and dazzle the public) was something in which you showed off, were a virtuoso, set yourself up to be something remarkable (24).

Talk about a warm welcome to writer’s block!

Brenda Ueland added in a footnote, Remember though that any motive that makes you feel like writing is fine. Use it. Start. If you want to dazzle the public, try it. Good luck to you. In my case it was an inhibition and resulted in nauseous work and I just want to explain that after a while the public-dazzling motive may give out and your results disappoint you. But if egotism and exhibitionism started you working I am grateful. It. . .will pass through. . . and tap a greater and more exuberant motive (p. 24).

She clinches her conclusion with, When I learned all this then I could write freely and jovially and not feel contracted and guilty about being such a conceited ass; and not feel driven to work by grim resolution, by jaw-grinding ambition to succeed, like some of those success-driven business men who, in their concern with action and egoistic striving, forget all about love and the imagination and become sooner or later emotionally arthritic and spiritually as calcified and uncreative as mummies (p. 25).

Critics

Who are the critics? I imagine them in a broad sense as anyone who deals with writers and writing. They are the agents who agree or “pass on” (as in “I’m afraid XYC Literary Agency is going to have to take a pass on) representing you. They may be editors throughout the process who love the bottom line more than they love your book. They may be the reviewers who hold forth after your book is published. Brenda Ueland imagined them as those who “Both obstruct and frighten imagination way, in themselves and others. . . .[They] theorize critically only when inspiration has died down. But inspiration only dies down because the theoreticians, the horses of instruction, begin to dissect, analyze, and then codify into rules what yesterday’s great artists did freely from their true selves” (p. 171).

“Another reason I don’t like critics (the one in myself as well as in other people),” Brenda Ueland wrote, “is that they try to teach something without being in it” (p. 172). She explains, “Now to have things alive and interesting it must be personal, it must come from the ‘I’; what I know and feel. For that is the only great and interesting thing” (p. 71).

Of course, her description of critics – no matter their role in the process of publishing your book – is not true of most critics. Brenda Ueland describes what she would have done as a critic: “Instead I just told her how good it was, how interesting and showed her places that proved it. ‘Tell more,’ I said. ‘Tell everything you can possibly think of. You speak here of this truck-driver whose tight clothes fitted him like the skin of a bulldog. What a bright picture. . . .’” (p. 72).

Publishing

My books, so far, have been published by publishers who worked with educational organizations or independent educational publishers, so I’m not going to pretend to know much about publishers of mainstream fiction or nonfiction. Lots of books and websites are out there to help you, however.

I do know that almost all publishers require a first-time author to submit through an agent, so your first step is to prepare materials for an agent: a cover letter, a bio, a synopsis, the first X pages of your writing, etc. Sometimes agents have a contract with a company such as Query Manager that allows you to complete a form online, send it in, and track it as it moves through the process. Agents’ requirements vary, so study them carefully and adhere to them religiously.

I wish publishing weren’t so important. Unfortunately, it signals WRITER, not writer. A student said to Julia Cameron, “’I think if I ever got published, then I would believe I was a writer’” (p. 115). Julia Cameron explained,

Writing for the sake of writing, writing that draws its credibility from its very existence, is a foreign idea to most Americans. As a culture, we want cash on the barrel head. We want writing to earn dollars and sense so that it makes sense to us. We have a conviction which is naïve and misplaced – that being published has to do with being “good” while not being published has to do with being “amateur.” We treat the unpublished writer as though he or she suffers an embarrassing case of unrequited love. We say things like “You may not want to put all your eggs into one basket.” And “You might want something to fall back on.” Books proliferate on what we “should” be writing and how we can “write for the market.” There’s not much advice along the lines of “Write what would make you happy.” There is something patently foolish, it would seem in doing something just for the love of it (p. 114).

It’s hard not to be skeptical about agents and publishers. Rita Mae Brown commented,

“The first thing I’ve learned is that very often people read their book, not your book. They read as though they were writing the book, and of course they would do things differently” (p. 151).

Anne Lamott got right to the point: “All right, let’s talk about publication. Let’s talk about the myth of publication” (p. 208).

Many authors put a screen between themselves and publication; they don’t let themselves see what’s behind the screen but write for themselves. Anne Lamott wrote, “Twice now I have written books that began as presents to people I loved who were going to die. . . .[one] about our experience, showing one family’s attempt to stay buoyant in the face of such a potentially flattening experience [cancer]” (p. 187). Then, it “seemed like it might be a welcome present to other people with sick relatives” (p. 188).

Finally, Lamott warns, “Publication is not going to change your life or solve your problems. Publication will not make you more confident or beautiful, and it will probably not make you any richer” (p. 185).

Don’t think too much about publication while you’re writing; don’t write to be published.

Recognizing Excuses

Develop a DEW system to identify possible excuses. Way back “when” (in the 1950s during the Cold War), DEW stood for Distant Early Warning system. It comprised 60 radar installations designed to warn the United States about the launch from the former Soviet Union of ICBMs (intercontinental ballistic missiles) that would reach their target somewhere in the United States in something like three minutes. Never happened, thank goodness; never needed.

Your own DEW system can warn you, however, that you may be launching excuses for not writing. If you hear yourself internally or aloud saying any of these phrases, pay attention. Your own brain may be attacked.

- I would love to write, but. . . .

- I’m not uneasy, just a little quivery, perhaps hungry. I must keep writing.

- Everything has already been written and better than anything I’d turn out.

- I’m already running out of ideas.

- I’m not a writer. I can’t even think of a title for this book (or anything else that seems a shortcoming)

- I don’t have the discipline to be a writer.

- People will laugh when I tell them I am writing.

- People will snicker behind their hands when they read what I’ve written.

- From the start writers create the most beautiful sentences.

- Writers have a deep well of plots, characters, and ideas – always available to them.

- Writing is uncomfortable for me; it’s hard.

- I’ll never make any money by writing.

- What’s the point if I cannot write an immediate bestseller?

- I don’t have the courage to write.

- I hate being alone.

- I’ll start tomorrow.

- I’ll become a writer when I have enough free time.

- I’m a perfectionist; it’ll take me one day to write a good sentence.

- I hate routines.

- I can’t plan or organize stuff enough to write.

- I hate feedback.

- I have difficulty just letting go and letting “it” happen.

- I have no imagination; I am not creative.

These excuses scream, “Stuck!” or “Blocked!” As Annie Dillard wrote earlier, “Don’t do nothing about them.”

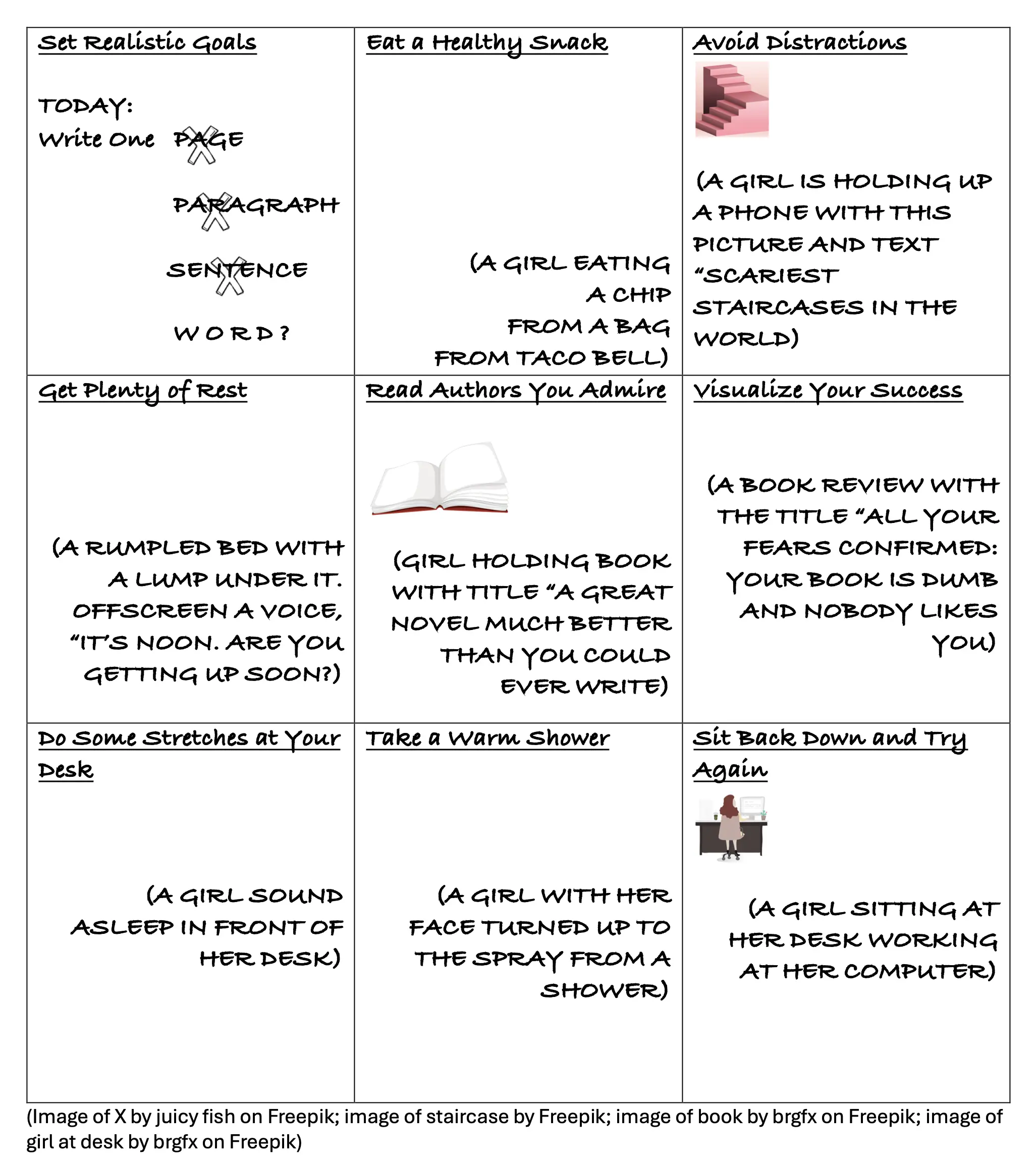

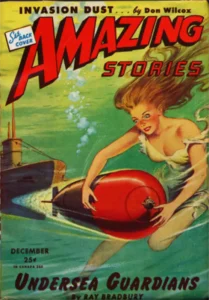

An Illustrated Self-Help Guide to Getting Un-stuck From Creative Paralysis