Most writers dislike revising and editing. If you haven’t reached this stage in the writing process, you may be dreading it. If you have, you may dislike it as much as most writers. Or you may feel as I do.

I enjoy this part of the process because it means that I have written something. I’m not staring at a blank page. I have something to work with, something I can improve.

During most of the writing process, I do not see very clearly. Writing is like making my way through fog. I can’t do much to make the fog disappear. All I can do is lurch through the murkiness waiting for the fog to part itself and reveal some clear sky. (Lurching is apparently good for me, however. By the time the fog has disbanded, I can write again.)

The title of this blog, “I Can See Clearly Now,” suggests that a whole draft is ready for the blue-sky work of revising and editing. In fact, the chorus of this song written in 1972 by Johnny Nash (covered by many other artists and included in the movie Cool Runnings) is

I can see clearly now the rain is gone

I can see all obstacles in my way

Gone are the dark clouds that had me blind

That’s how I feel, and perhaps I can help you feel that way too

If I can’t, perhaps Stephen King can: “I love this part of the process (well, I love all the parts of the process but this one is especially nice) because I’m rediscovering my book, and usually liking it. That changes. By the time a book is actually in print, I’ve been over it a dozen times or more, can quote whole passages, and only wish the damned old smelly thing would go away” (pp. 213-4).

A Given First Draft

Here is the first draft of several paragraphs that need revision and editing. We’ll return to this draft at several points in this blog, but you don’t need to do anything with it now.

If he said anything to June. He was mean and rude. Between you and I he was cruel, but that was just him saying stuff. Just Ronalds’ way. He’s a just a teenager that doesn’t know nothing. June she is just so sweat. What should we do I asked? Kenny sat in the quite park, scrapped his feet on the gravel to swing back and fourth. They squealed.

I said she just sits their, gives me the willys as I look at the both of them, he and she. He needs to changes and so does her. Kenny says could teach June to talk back. Turn her back back away. And pumps his swing highest. I know.

Don’t you never call me Angel. I am Angelica I’ll have you you know. Your in as much trouble as Ronald. Oh come on everybody calls you AN JELLO CO. She got off her swing and goes to his swing. Before he knew it he lands on all that gravel. Angelica backs away turns her back talked back. Is this about me and you? Or Kenny and June?

Revision

Revision and Redecorating

Imagine that you are planning to redecorate your house. Your friend offers to help and brings over a vase you have never seen before. You don’t know what to say, so you say “thank you.” You’re somewhat surprised when your friend says, “So call me if you need more help.

Revision is a big job, similar to redecorating an apartment or home, or renovating an office building or showroom floor.

Revision also applies to an individual (but whole) room: a bedroom, an office, or a garage

Editing is more like sprucing up a room with a vase (or, as pictured, a pot). It is distinct from other single actions that a writer does, something like a touch up, or a patch up. It is not the whole of an action, which describes revision, just a (tiny) part (Image by wayhomestudio on Freepik)

P.S. An edit should fit within the whole. Unless you want your house to have a Southwestern motif, with some objects light purple or pink, your friend’s gift may be unsuitable. Perhaps he should have inquired.

Another way to think of revision is as RE VISION or seeing again. I find that idea exhilarating. Just think: If I had to send off my first draft for evaluation, I’d be sunk before I’d licked the first postage stamp. Thank goodness I am allowed (nay, encouraged!) to see my first draft again and, perhaps, again and again, until I won’t be completely embarrassed by it.

When to Revise

I was told NEVER REVISE WHILE YOU’RE WRITING YOUR FIRST DRAFT when I was working on my first book, but I couldn’t help myself. When I felt a bit of uneasiness about what I was writing (a sentence, paragraph, section, or entire chapter), I saw no point in going further. . . in perpetuating what didn’t feel right to me. When my mind simply stopped because something didn’t feel right, my pen or fingers on the keyboard did the same.

So I spent on rewriting a fair amount of time I had supposedly dedicated to writing.

Sometimes, I knew to stop in the middle of whatever I was writing. Sometimes, I knew to stop when I reread some part of what I had already written to get started on the new writing.

Whenever the urge to rewrite stopped the flow of my words, I stopped. Call it intuition, a hunch, a gut reaction, or just a niggling feeling throughout my body, I trusted it. I stopped and usually disengaged from my writing for a while (taking a walk, reading, napping) to discern the problem.

I am not recommending that you stop writing your first draft to rewrite some part of it. I am not recommending that you reread what you have written before you restart your writing (or for any other reason). Please read the following advice about when to revise from other authors and then see what works for you.

P.S. The standard procedure is to revise FIRST and then EDIT. It makes no sense to edit something you will then revise. However, I am not averse to editing whenever I catch a minor spelling, usage, punctuation error when I see, whether during the writing of a draft, while I’m rereading some part, during revision, or after revision.

Here’s what other authors advise;

“Don’t look back until you’ve written an entire draft, just begin each day from the last sentence you wrote the preceding day,” said Will Self, an English writer who has written 11 novels, shorter fiction, and non-fiction.

American writer Julia Cameron, known for The Right to Write and The Artist’s Way, warned, “The danger of writing and rewriting at the same time was that it was tied into my mood. In an expansive mood, whatever I wrote was great. In a constricted mood, nothing was good. This made writing a roller coaster of judgment and indictment: guilty or innocent, good or bad, off with its head or allowed to go scot-free. I wanted a saner, less extreme way to write than this. I wanted emotional sobriety in my writing” (pp. 18-9).

She described how she achieved sobriety in her writing: “. . .I learned to write setting judgment aside and save a polish for later. I called this new, freer writing ‘laying track.’ For the first time I gave myself emotional permission to do rough drafts and for those rough drafts to be, well, rough” (p. 19).

How did her technique work? “Freed to be rough, my writing actually became smoother. Freed from the demand that it be instantly brilliant, perfect, and clever, my writing became not only smoother but also easier and more clear. When I went back to polish, I found there wasn’t that much to fix of change” (p. 19).

Stephen King – The King of Horror – advised, “Resist temptation. If you don’t, you’ll very likely decide you didn’t do as well on that passage as you thought, and you’d better retool it on the spot. This is bad” (pp. 211-12).

He explained, “If I write rapidly, putting down m story exactly as it comes into my mind, only looking back to check the names of my characters and the relevant parts of their back stories, I find that I can keep up with my original enthusiasm and at the same time outrun the self-doubt that’s always waiting settle in” (p. 209). I like what he said about outrunning the self-doubt.

He cautioned writers about sharing their first drafts: “My best advice is the resist this impulse. Keep the pressure on; don’t lower it by exposing what you’re written to the doubt, praise, or even the well-meaning questions of someone from the Outside World. Let your hope of success (and your fear of failure) carry you on, difficult as that can be” (p. 210).

Letting Your First Draft Rest

Neil Gaiman, an English author of short fiction, novels, comic books, graphic novels, and screenplays, suggested, “Put it aside. Read it pretending you’ve never read it before.”

Zadie Smith, also an English novelist who wrote White Teeth, Swing Time, and The Fraud, echoed that sentiment, “Leave a decent space of time between writing something and editing it.” (Zadie Smith)

A minimum of six is about right for Stephen King: “How long you let your book rest—sort of like bread dough between kneadings—is entirely up to you, but I think it should be a minimum of six weeks. During this time your manuscript will be safely shut away in a desk drawer, aging and (one hopes) mellowing. Your thoughts will turn to it frequently, and you’ll likely be tempted a dozen times or more to take it out, if only to re-read some passage that seems particularly fine in your memory, something you’d like to go back to so you can re-experience what a really excellent writer you are” (p. 211).

“If you’ve never done it before, you’ll find reading your book after a six-week layoff to be a strange, often exhilarating experience” (p. 212).

“Within six weeks’ worth of recuperation time, you’ll also be able to see any glaring holes in the plot or character development. I’m talking about holes big enough to drive a truck through. It’s amazing how some of these things can elude the writer while he or she is occupied with the daily work of composition. And listen—if you spot a few of these big holes, you are forbidden to feel depressed about them or to beat up on yourself” (213).

The Rub of Revising

Most writers agree that the worst part of revising is cutting. In Blog 5 Dropping In On The Absolutes, I talked about comfort with change as an absolute condition for writing. Under the heading “MURDER YOUR DARLINGS!” and a picture of a bloody knife, I cautioned that writers need to be able to let go of something that’s not quite working. (Image by freepik)

Most writers agree that the worst part of revising is cutting. In Blog 5 Dropping In On The Absolutes, I talked about comfort with change as an absolute condition for writing. Under the heading “MURDER YOUR DARLINGS!” and a picture of a bloody knife, I cautioned that writers need to be able to let go of something that’s not quite working. (Image by freepik)

I quoted from several authors:

Diana Athill (a British literary editor, novelist, and memoirist) wrote, “Cut (perhaps this should be CUT): only by having no inessential words can every essential word be made to count.”

She elaborated on the painful process: “You don’t always have to go so far as to murder your darlings – those turns of phrase or images of which you felt extra proud when they appeared on the page – but go back and look at them with a very beady eye. Almost always it turns out that they’d be better dead.”

Roddy Doyle (an Irish novelist, dramatist, and screenwriter) commented, “Do change your mind. Good ideas are often murdered by better ones.”

Stephen King (oft-mentioned in these blogs as the King of Horror) put a percent to the number of words to cut: at least 10% of the first draft (p. 283). Here’s a rather benign example that illustrates “cutting to the “bone.” “The first draft copy reads ‘Mike sat down in one of the chairs in front of the desk.’ Well, duh—where else is he going to sit? On the floor?” (p. 283).

One word or more

A sentence or more

A paragraph or more

A section or more

A chapter (Ouch! It’s beginning to hurt!) or more

A character (Oooo!)

A setting

A part of the plot (Damn painful)

The title

The purpose (Yikes!)

An Author’s View of Revision

Stephen King, in his superb book On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, describes how he revises: “. . . I’m asking myself the Big Questions. The biggest: Is this story coherent? And if it is, what will turn coherence into a song? What are the recurring elements? Do they entwine and make a theme? I’m asking myself What’s it all about, Stevie, in other words, and what I can do to make those underlying concerns even clearer. What I want is resonance, something that will linger for a little while in Constant Reader’s mind (and heart) after he or she has closed the book and put it up on the shelf” (p. 214).

“Most of all, I’m looking for what I meant, because in the second draft I’ll want to add scenes and incidents that reinforce that meaning. I’ll also want to delete stuff that goes in other directions. There’s apt to be a lot of that stuff, especially near the beginning of a story, when I have a tendency to flail. All that thrashing around has to go if I am to achieve anything like a unified effect. When I’ve finished reading and making all my little anal-retentive revisions, it’s time to open the door and show what I’ve written to four or five close friends who have indicated a willingness to work” (p. 214).

Thank you for putting it so well, Mr. King.

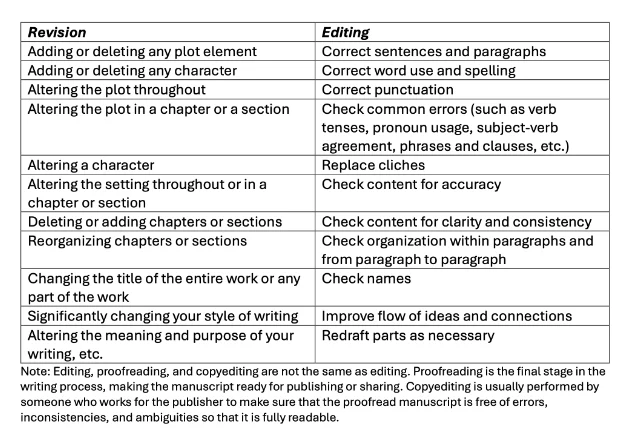

Comparing the Activities of Revising and Editing

Revise the Given First Draft

Use what you have learned in this part of the blog to determine how you would the First Draft about Kenny, June, Ronald, and Angelica. List what you would do and then go to the end of this blog to read what I would do.

Editing

Congratulations! You’ve done the hardest one of these dual duties, at least in my opinion. You’re all by yourself when you revise. You can’t just lift a sure-fire how-to revise for your idiosyncratic book, story, essay, screenplay, etc.

Here are the “toolbox concerns” that Stephen King focuses on while editing: “. . .knocking out pronouns with unclear antecedents (I hate and mistrust pronouns, ever one of them as slippery as a fly-by-night personal-injury lawyer), adding clarifying phrases where they seem necessary, and of course, deleting all the adverbs I can bear to part with (never all of them; never enough)” (p. 214).

Rules That Rule Editing

Yes, there are rules. Sometimes these are softened as “tips” or “suggestions.” But you’ll have to face it: there are rules for SAE (Standard American English). What is SAE? It is what writers and speakers use for formal and professional purposes. It’s what you’ll hear on newscasts and conventional podcasts. It’s what you’ll read in textbooks and scholarly books.

There’s certainly some conflict about both the word “Standard” and the word “American.” Language changes constantly, so there’s probably no time when English is exactly the same for all people who write or speak English. Also, it’s not the language all Americans use. A document called “Sound Writing” from the University of Puget Sound thoroughly explores the problems of SAE (also known as AE or Academic English or SEAE or Standard Edited American English, as it “is privileged by those who historically hold power in the academy and our society as a whole” (https://soundwriting.pugetsound.edu/universal/SAE.html).

The authors of the paper describe how SAE “has often been used to normalize white, middle- and upper-class language systems and to denigrate language systems that differ from them (and that hence, become “non-standard” and “improper”).

You are probably familiar with most of the SAE rules of grammar, usage, and mechanics (which I call GUM because they sometimes gum up how language works). There are other rule-driven and systematic languages, such as

AAE (African American English) – a variety of English spoken by some Americans (also rule-governed and systematic)

- Chicano English/Mexican American English

- Cajun English

- Hawaiian Pidgin (also called Hawaiian Pidgin English and Hawaiian Creole English)

- Southern White American English

- American Sign Language

Finally, there are other uses of language that are not obviously rule-driven or systematic:

- Jargon – the special words or expressions used by people in particular professions and not difficult to understand by others.

- Dialect – the regional variety of a language

- Slang – an informal language used by particular groups of people or in particular situations, more common in speech than writing

You will need to think about your characters, setting, history, culture, plot (and other elements of your narrative) to decide the language you will use.

I will not discuss the rules of SAE in this blog, but I will in Blog #20, “The Rules and How (and When) to Break Them.”

Resources for Editing

At least you have multiple resources available to you for editing, from grammar books to explanations of editing symbols and from online worksheets to manuals of style. Here are just a few I’d recommend:

- Strunk, William, Jr., and White, E. B. (1959) The Elements of Style.

This is the classic, sometimes called The Strunk and White. My copy was not the first published – that was in 1918 by Strunk – and it won’t be the last. My 1959 version led through high school to a diploma, through college to a diploma, through graduate school to my M.A. and Ph.D, and through numerous articles and books. The most current edition is 2022 (with Strunk as author and Bobby C. Carlos as editor). Mine was 71 pages, and the 2022 version is 63 pages. The book follows its own advice: “Omit needless words.”

In case you need more persuasion, here’s what American humorist Dorothy Parker said about The Elements: “If you have any young friends who aspire to become writers, the second-greatest favor you can do them is to present them with copies of The Elements of Style. The first-greatest, of course, is to shoot them now, while they’re happy” (Esquire, Vol. LII, No. 5, pp. 26-28). - The Chicago Manual of Style.

This is the industry manual, used by writers, publishers, editors, proofreaders, anyone who needs to know more grammar, usage, mechanics, and spelling than anyone else. The 17th edition is a whopping 1,146 pages; the 18th edition will be released on September 19, 2024. Your best bet is to use the online version (https://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org). - What Editors Do by Peter Ginna

This is about the profession but gives the reader stories that are specific enough for gleaning techniques of editing. - The Best Punctuation Book, Period: A Comprehensive Guide for Every Writer, Editor, Student and Businessperson by June Casagrande.

With a title like that, I couldn’t pass on this one. Yes, sure, I’m a punctuation nerd, but I’m nerdy in other ways (such as loving to diagram sentences). The author references other style guides and distinguishes among them, ultimately to come up with her own master list of rules for punctuation. - Roget’s International Thesaurus by Dr. Peter Mark Roget (earliest edition 1852; most recent edition 2023)

You might not expect a thesaurus to be listed as a resource for editing, but I never miss a chance to tout the benefits of a thesaurus, especially a Roget thesaurus. Roget organized his thesaurus (from the Greek and Latin, meaning ‘treasure’ or ‘storehouse’) unlike dictionaries and other thesauri. He organized them according to ideas not according to the alphabet. Readers use an index (alphabetical in nature) to find the word they want and then turn to the number of the word. What’s so exciting is that the word is surrounded by related words, including synonyms and antonyms, and related ideas. For example, look up ear in the index, and turn to the page that includes the word ear, and you’ll find it classified in a large section called THE BODY (physical self). First, you’ll find nouns and, later, adjectives. Along with the word ear you’ll find words and phrases that relate to the ear. You can choose from nearly 70 other words to replace ear, from auricle to cauliflower ear, from tympanic cavity to bony labyrinth. If you have written ear 30 times in a paragraph, a Roget’s can help you use another word or two that will serve your purpose. - Some websites:

https://www.grammarly.com (you download the program that works with the app you use to write)

https://nybookeditors.com/2016/02/instantly-improve-your-writing-with-these-11-editing-tools/ (has several writing tools/software; for example, Manuscript Editing Software for Fiction Writing)

https://hemingwayapp.com/ (I couldn’t pass this up. After all, Hemingway! This app color codes your writing problems: yellow, red, or blue. AI helps you fix things up.)

Editing (Proofreading) Marks - Real

Finally, you have a tool that you might find very useful, no matter what language you are editing. These are called “proofreading” symbols, but they can be used to edit, as well. They were published in “Editing Marks: Real and Imagined” by Nancy Miller in the online magazine Medium (medium.com/@stephanieayers/editing-marks-real-and-imagined-195a87093d14). They were originally published by J. Weston Welch, Publisher, in 1965.

Finally, you have a tool that you might find very useful, no matter what language you are editing. These are called “proofreading” symbols, but they can be used to edit, as well. They were published in “Editing Marks: Real and Imagined” by Nancy Miller in the online magazine Medium (medium.com/@stephanieayers/editing-marks-real-and-imagined-195a87093d14). They were originally published by J. Weston Welch, Publisher, in 1965.

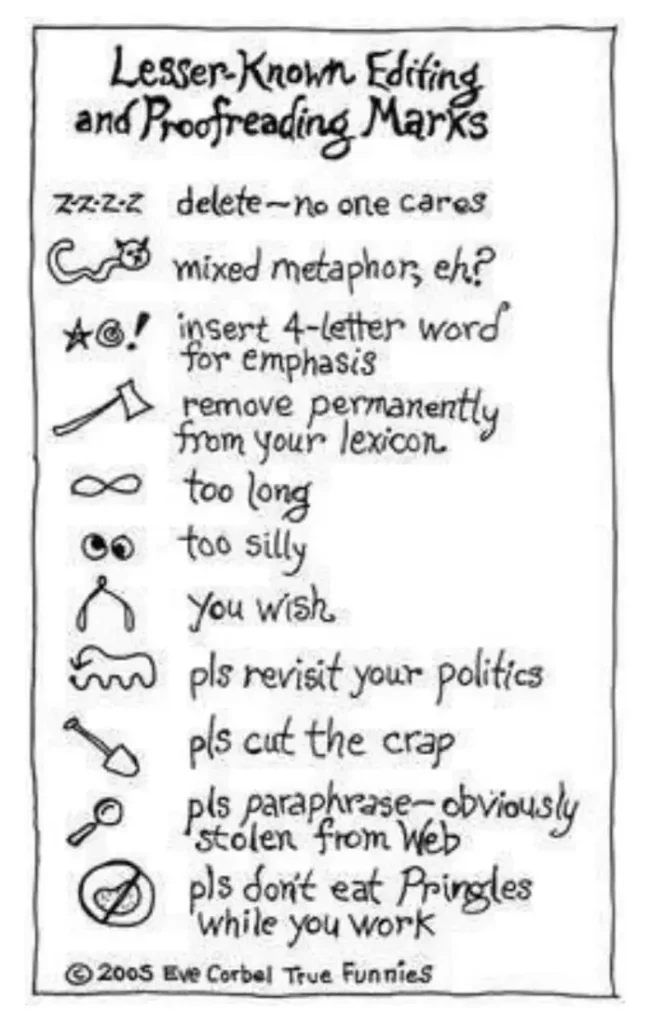

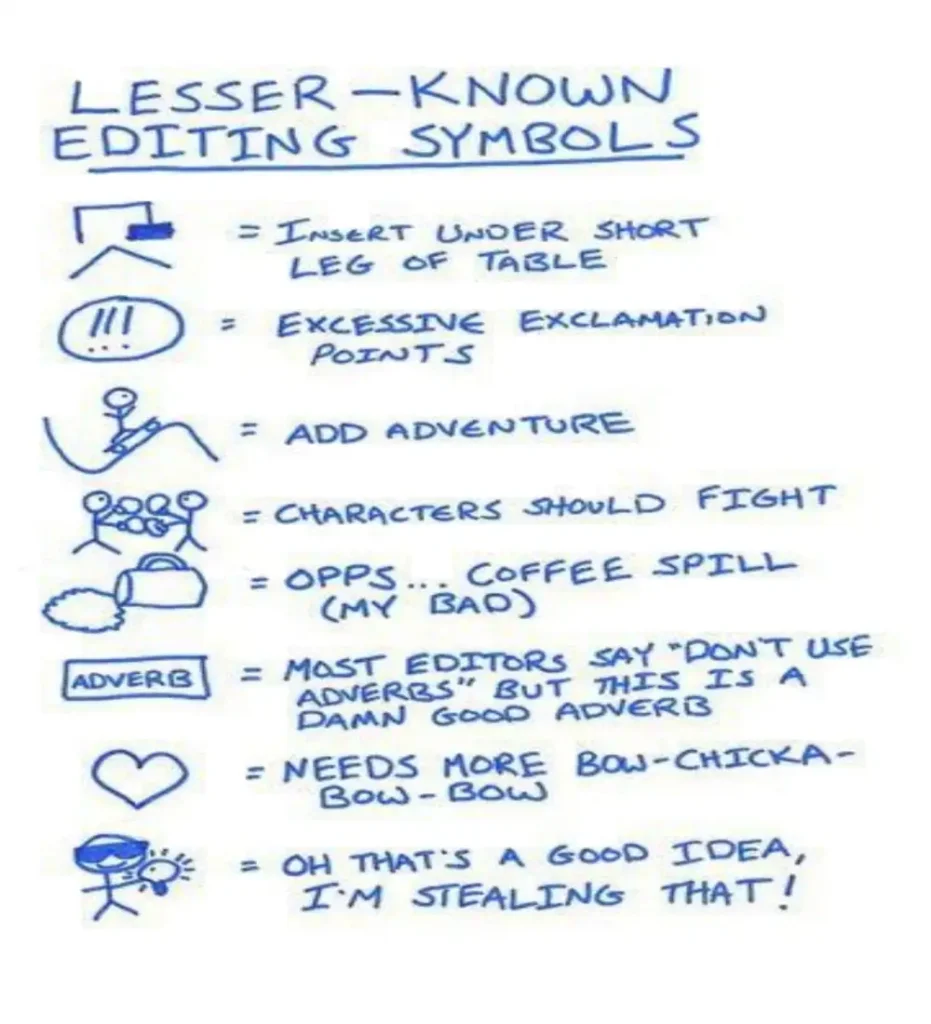

Editing (Proofreading) Marks – Imagined

The following are two “imagined editing marks.” Enjoy!

Use of real or imagined marks has fallen “out of use” because computer software, such as Microsoft Word, allows writers to highlight and then comment on a word or phrase. (Note: in the box labeled “Lesser-Known Editing Symbols” the word OOPS is spelled wrong.)

Edit the Given First Draft

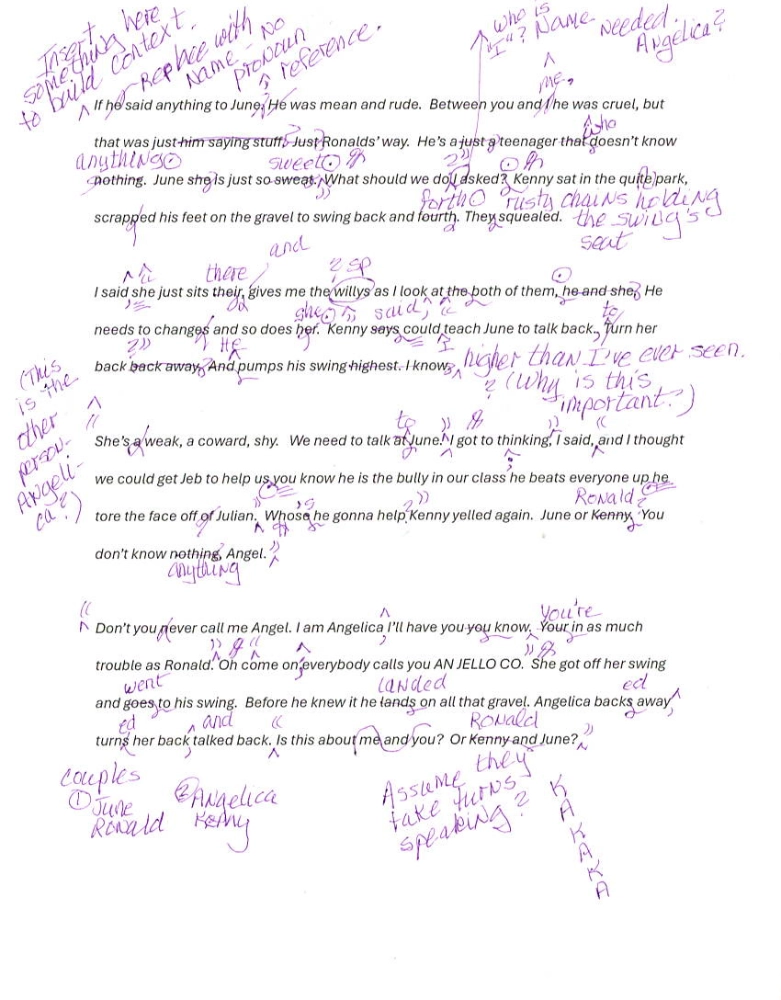

Use the editing/proofreading marks to edit the Given First Draft at the beginning of this blog and then look at my comments at the end of this blog. You can print out this section and actually use the marks or simply imagine what you would mark and why.

My Comments on Revising and Editing the Given First Draft

Here is the first draft I presented at the beginning of this blog:

If he said anything to June. He was mean and rude. Between you and I he was cruel, but that was just him saying stuff. Just Ronalds’ way. He’s a just a teenager that doesn’t know nothing. June she is just so sweat. What should we do I asked? Kenny sat in the quite park, scrapped his feet on the gravel to swing back and fourth. They squealed.

I said she just sits their, gives me the willys as I look at the both of them, he and she. He needs to changes and so does her. Kenny says could teach June to talk back. Turn her back back away. And pumps his swing highest. I know.

She’s a weak, a coward, shy. We need to talk at June. I got to thinking, I said, and I thought we could get Jeb to help us you know he is the bully in our class he beats everyone up he tore the face off of Julian. Whose he gonna help Kenny yelled again. June or Kenny. You don’t know nothing, Angel.

Don’t you never call me Angel. I am Angelica I’ll have you you know. Your in as much trouble as Ronald. Oh come on everybody calls you AN JELLO CO. She got off her swing and goes to his swing. Before he knew it he lands on all that gravel. Angelica backs away turns her back talked back. Is this about me and you? Or Kenny and June?

At the beginning of this blog and inserted a few paragraphs

My Comments on Revising the Given First Draft

“If.”

Jeesh! What a start. The first word of the first sentence (or the first paragraph or the first chapter. Whatever. That’s lousy. If these paragraphs are all there is, I’d say there’s a lot missing. Since we don’t know if they came from the beginning, middle, or end of something longer, we must take them as they are.

I am so distracted by the editing problems, that I want to edit them first or concurrently, but I’m going to strive not to do so. So, some questions that lead to revision:

- Who are these characters? It’s June and someone else. Ronald? Or are these other characters talking about Ronald and June. Are there three characters? Four? More?

- Who’s “You” and who’s “I”?

- Which character is with which other character?

- Ah, we finally learn that there’s Kenny. Is Kenny talking to June? Or is Kenny talking to “You,” whoever she is?

- Who asks what to do?

- How old are the characters?

- Where are they?

- Who is the “I” in the second paragraph? Is this person talking to Ronald or Kenny (I think it’s Kenny).

- Who could teach June to talk back?

- Who is the person who says, “I know.” What does this person know? About Kenny’s swing? About someone else?

- What’s mean by combining “weak,” “coward,” and “shy”?

- Oh-oh. Now there’s Jeb. Who mentions Jeb? Who will Jeb help?

- What kind of person is Ronald? Kenny? Jeb? June? The other person?

- Finally, there’s Angel. She’s apparently talking with Kenny.

- Why is it a “no-no” to refer to Angelica as Angel? What’s the history? For that matter – again – what’s the relationship between the two? And between these two and the other two?

- They’re talking about June and Ronald.

- Apparently, Ronald is mean to June. Why?

- Why does June have anything to do with Ronald?

- Why should Kenny and Angel care?

- Were they watching? Did they do anything to stop Ronald’s behavior? Should they have done something? Are they older or do they have any responsibility for Ronald and June?

- Are any of these people brothers and sisters?

- Who’s Julian? Is Julian just one of the people Ronald has attacked?

- Why hasn’t someone else (teacher, parent, etc.) done anything about Ronald?

- Are these “kids” on their own (assuming the single age identifier “teenager” applies to all of them)?

- Is this a school (yes, it mentions “class”)? Reform school? Orphanage? Juvenile detention/prison?

- Is this a dystopia?

- Who is the writer directing this “story” to, and for what purpose?

- What is the writer’s attitude towards his characters? It seems almost disdainful, and that doesn’t make me care.

My Comments on Editing the Given First Draft

Here is the Given First Draft with my editing marks in purple. I never used a red pen when I taught writing – anything but red. So my marks are in purple (but not purple prose). Of course, I was not fooling anyone. I’m sure my pen marks were as intimidating as if they had been written in red, though I made my purple comments as helpful and positive as I could.

One Result of Revising and Editing the Given First Draft

First of all, this draft needed so much work that I would have revised it and edited it twice. The editing needs got in my way as I tried to revise it, so sometimes I attended to editing and then revision. Once I had revised and edited draft the first time, I revised and edited it a second time.

Since I didn’t have the writer to question, I invented some details that seemed reasonable to me. If I had been with the writer, I would have asked lots of questions about who the characters were, how they knew each other, and what had happened before the first sentence.

Naturally, you’ll have the writer – you – with you as you revise and edit, so an improved draft would have been much better (and more authentic) than the draft I revised and edited, leading to the next draft.

Here’s the best I could do with the next draft:

We had snuck off campus after ninth grade lunch – all four of us – and gone to the park about a half mile away. Even before we got there, Ronald and June had started squabbling. Kenny and I left them and continued towards the empty swings where we liked to sit when we played hooky.

Kenny commented as we swung gently back and forth, “If Ronald hadn’t said anything, they would have been okay, but he was mean and rude to June. Between you and me, he was cruel, but that’s just Ronald’s way. He’s a teenager who does know anything. June is just so sweet.”

I asked, “What should we do?”

Kenny sat in the quiet park, scrapping his feet on the gravel to swing back and forth. That and the squealing of the rusty chains that held the seat to the top of swing set were all we could hear.

I said, “She just stands there, giving me the willies as I look at both of them. He needs to change and so does she.”

Kenny said, “I could teach June to talk back.”

I added, “To turn her back.”

Kenny closed with the words “to back away,” and then he pumped his swing higher than I’ve ever seen, which was how I knew he was upset.

“She’s weak, a coward, shy. We need to talk to June. I got to thinking,” I said. “I thought we could get Jeb to help us. You know he is the bully in our class; he beats everyone up. He tore the face off Julian.”

“Who’s he gonna help?” Kenny yelled. “June or Ronald? You don’t know anything, Angel.”

“Don’t you ever call me Angel. I am Angelica, I’ll have you know. You’re in as much trouble as Ronald.”

“Oh, come on, everybody calls you AN JELLO CO.”

She pitched forward off her swing and stomped to Kenny’s swing. Before he knew it, he sge had grabbed the rusty chains and he fell backwards on all that gravel. Angelica backed away, turned her back, and talked back. “Is this about you and me?”

“Or Ronald and June?”

Yuck. Horrible story.

A Few Final Tips for R & E

- Allow yourself to revise and edit as you write the first draft, especially when you reread something and know that it’s not working or is wrong. Don’t go any further on the basis of what’s off beam.

- Reread as much as you’d like. Sometimes rereading will help you pick up the thread of what you were writing. Sometimes it will make you uneasy. If you’re uneasy, do something (see #1).

- Don’t be afraid to cut (but save everything you cut, every draft, every discard). Throw nothing away. You never know when you’ll want something you cut. You’ll never know that what seemed awful now fits quite well.

- Work sincerely, honoring your work. In other words, be nice to yourself. Ignore what doesn’t torment you; let it go until later. But don’t let yourself work on something that vexes you as you continue trying to write. (Image by fabrikasimf on Freepik)