Occasionally, as a writer you might want to yell about how sick you are of words, especially if you must find the right word “all day through” just to inch your manuscript into the next sentence or paragraph.

I’m so sick of words!

I get words all day through;

These sharp words came from the mouth of Eliza Doolittle in the musical My Fair Lady based on George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion. Phonetics Professor Henry Higgins hears Eliza’s offensive Cockney accent when she tries to sell flowers in Covent Garden. Higgins makes a bet with his friend Colonel Hugh Pickering that he can turn this ragamuffin girl into an elegant young woman who can pass as a duchess at a ball. As a “duchess,” Eliza attracts the aristocrat Freddy Eynsford-Hill, who pledges his love to her. She responds to his words with:

Words, words, words

I’m so sick of words!

I get words all day through,

First from him [Professor Higgins], now from you!

Is that all you blighters can do?

She demands that he cease talking:

If you’re in love

Show me!

(Image by pikisuperstar on Freepik)

[Fittingly, writers have adopted the admonition of showing not telling.]

Wordstruck

Not everyone is sick of words, however. Author Rita Mae Brown wrote, “A word leaves a smoke trail behind it that curls into the past. . . . A word can sweep by your ear and by its very sound suggest hidden meanings, preconscious association” (p. 57).

Robert MacNeil wrote an aptly named book Wordstruck: “Wordstruck is exactly what I was – and still am: crazy about the sound of words, the look of words, the taste of words, the feeling for words on the tongue and in the mind” (preface).”

I love words, too. You may think this is geeky, but members of my family examine a word-a-day at dinnertime, guessing its meaning (sometimes wildly off the mark), comparing their guesses to the real meaning, getting to know its derivation, and trying to use it in a meaningful sentence.

Some Basics

This blog is not about grammar and usage; you’ll have to wait for Blog 20 to get to some word rules and how (and when) to break them. This blog is about using the right words for reasons other than rules. Rita Mae Brown referred to Mark Twain to emphasize that ‘the difference between the right word and the almost right word is the difference between lightning and lightning-bug.” (59)

Denotation and Connotation

You’ve probably heard these words before: denotation and connotation. They describe characteristics of the word choices you make. Understanding both the denotations and connotations of the words you choose are vital when you are writing for an audience (readers or listeners). Here’s a way to understand these two words visually:

Let’s say that you want to write about a girl on a street. Which picture shows a girl on a street without much emotional baggage? It is true, faithful, and literal. Although you can conjure a feeling associated with the picture in color, the photographer shot the picture for its denotation, its fidelity to the words: girl and on a street. It doesn’t go much beyond the matter of fact.

The black and white picture shows the same thing but invokes more. It is about a girl on a street but is focused on the connotation, the feelings or emotions the photographer probably had in mind while shooting the picture. It’s black and white, not color, and it is dark. The streetlights make the rest of the picture seem even darker. The girl in the black and white photograph seems to have come from darkness and might continue in darkness. The girl in the colored photograph is in light and may have people around her (witness the vehicles and the cones indicating a “no parking” or “construction” zone, both of which might involve people). Besides, she is in touch with someone on her cellphone.

I was worried about the girl in and black and white photograph, imagining some threat to her. I had no worries about the girl in the colored photograph. The black and white picture felt spooky to me, but the other picture felt “normal.” I became anxious about the girl in the black and white picture and hoped she’d be safe; I didn’t feel much of anything about the girl in the colored picture. I just noted that the picture was of a girl on a street.

For your reference, some definitions:

Denotation = the direct or primary meaning of a word; reality; not including the feelings or ideas people may attach to the word

Connotation = the ideas or emotions invoked by a word; feelings embedded in a word, beyond its primary meaning

What do each of these word pairs from www.litcharts.com/ denote?

Which word in each pair seems to have a connotative value?

- Chef and Cook

- House and Home

- Shrewd and Clever

- Skinny and Slim

- Journalist and Newshound

(Denotations are 1. Someone who prepares food; 2. A place where people live; 3. Intelligence; 4. Thinness; 5. News reporters. Words that seem to have strong connotations are 1. Chef; 2. Home; 3. Shrewd; 4. Either word; 5. Newshound)

Because all words have a denotation and most words a connotation, writers need two valuable references book (or online sources) for words they want to use in writing (from https://www.freepik.com/author/lesyaskripak.)

I have already extolled the value of a thesaurus (see Blog 16). My favorite thesaurus is the hardback of Roget’s International Thesaurus by Dr. Peter Mark Roget (earliest edition 1852; most recent edition 2023). I also use online sites that list synonyms for words I want to replace.

But Roget’s gives me related words and their opposites. He did not organize his thesaurus alphabetically; he organized it according to ideas. His thesaurus is a map to a universe of words. I look up the word I want to replace in an index (organized alphabetically) at the back of the book. I use the number given for that word to find it in the front of the book. What’s so exciting is that the word I want is surrounded by related ideas as well as synonyms and antonyms that are typical online or in alphabetically arranged thesauri. words, including synonyms and antonyms, and related ideas.

For example, look up petulant in the index, which is followed in my thesaurus by the number 574; turn to that number in the first part of the thesaurus. No problem finding the word, but you’ll also find how it fits in bigger categories (which is called a taxonomy or classification according to common/shared characteristics), from broadest (in science kingdom) to narrowest (in science, species), like this for petulant:

There’s my word, along with other nouns, lots of adjectives and adverbs, some phrases, and some antonyms under the key word feebleness. If I’m still not satisfied, I can roam around in Various Qualities of Style such as perspicuity, obscurity, conciseness, diffuseness, plainness, ornament, elegance, and inelegance.

Pardon my overenthusiasm for the Roget’s version of a thesaurus! It doth run over.

Is a thesaurus enough? No. It gives you many words from which you can choose the best. But is your choice the best? Are your confident about the meaning of the word you chose? The best device for checking the exact – and current – meaning is the dictionary, online, paperback, or hardback.

Let’s say I chose the word sublime to replace petulant. Both words are in 574. But the online Merriam-Webster definition is “lofty, grand, or exalted in thought, expression, or manner.” M-W defines petulant as “insolent or rude in speech or behavior; characterized by temporary or capricious ill humor: peevish. Oh-oh. Though grouped together, one or the other word has changed meaning over time. I cannot substitute sublime for petulant. Perhaps I can select another word in the set: forceful, powerful, trenchant, mordant, biting, incisive, impressive, sensational, spirited, lively, racy, bold, slashing, pungent, piquant, full of point, pointed, pithy, antithetical, sententious. I choose biting.

The Power of Verbs

According to writer Rita Mae Brown, verbs “put the pedal to the metal” (p. 67). She wrote:

“Verbs blast you down the highway. If you want to get your black belt in boredom, load your sentences with variations of the verb to be. Granted, sometimes you can’t help using them, especially with nonfiction, but at every opportunity knock out is, are, was, etc., and insert something hot. Strong verbs are always hot” (p. 67).

She suggests that writers need to listen to the verbs they use, so read your work aloud and circle the verbs. Strong verbs sound different from weak verbs: “As a writer you’ve got to hear them like separate notes on a scale”(p. 67). Listen for the pace of your sentences within a paragraph or section of your writing. The to be verbs don’t do much for a sentence. They are not impressive. They are so-so, apathetic, indifferent. Meh.

(See Blog 10 Pacing: Eating Raw Rhubarb for more on pacing.)

Of course, to be verbs are among the other verbs that help change the tense or time of an action:

Talk. . .am talking. . . is talking. . .was talking. . .will be talking. . . .

Explode. . .will explode. . . has exploded. . .would have exploded. . .had exploded. . . .

But, if they stand alone, they are passionless:

Am. . .is. . .are. . .were. . . be. . . being. . .been

- CHANGE The farmer is loud when he calls his cows TO The farmer bellows when he calls his cows.

- CHANGE The pie was excellent TO The pie evoked peaches at their peak.

- CHANGE They are the best debate team in Madison TO They triumphed over all the other debate teams in Madison.

- CHANGE It is my plan to circumnavigate the earth on a skateboard TO I’ve dared myself to circumnavigate the earth on a skateboard.

- CHANGE Haviland Road is too narrow for the number of cars on it during rush hour TO Haviland Road packs cars on its narrow lanes during rush hour.

According to Brown, “the to be family falls flat on its face with overuse. “I’m not saying that weak verbs lack punch—it depends on the sentence—but I am saying that the ‘to be’ family falls flat on its face with overuse.” (67)

Tenses

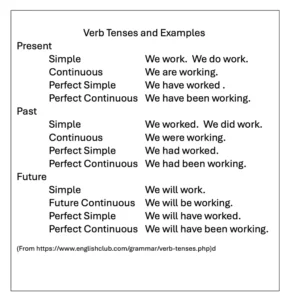

I am tense challenged. I begin with what seems the best available verb tense to tell my story (see the list and examples in the box), but I wander away from my choice and not always purposefully. Sometimes I detect my meandering only when I revise and edit part of what I’ve written. Reading a piece aloud sometimes makes tense changes more evident than reading it silently.

I did quite well with three tenses (present, past, future) until I took a language other than English. Now I am aware of 12 tenses (see box).

I did quite well with three tenses (present, past, future) until I took a language other than English. Now I am aware of 12 tenses (see box).

You don’t need to memorize these tenses. You just need to be aware of the main tense you are writing in – probably present or past simple – and when you need to vary it for special purposes.

When you reread, revise, and edit your work, be aware when you slide from one tense (such as present simple) to another (such as present past) for no particular reason.

For example, I wrote this in an early draft of my novel Through the Five Genii Gate:

Kathryn walks across the road between the residences and the dormitory, opened the front door, walked a few paces inside, and finds herself looking down a hallway to the right and left. The space is empty and dark. Where is everybody? She turned left and opened a door; within, she sees rows of bunk beds. She went back to the entrance and turned right. This time she finds a single room, empty of all possessions but functional with a made-up single bed, a bedside table, a wardrobe. . . .

You probably detected the shift between present and past tenses (simple), but as I wrote the passage, knowing it was in the past, I kept seeing my character doing these things in the present.My writing was doing the past tense while my mind was doing present tense. As I read the passage aloud, I groaned. I had crossed the lines between tenses again. It was simple to return to consistent use of the past tense.

I could have used another verb tense in that paragraph if I had set up the sentence appropriately. For example, it would be reasonable for Kathryn to say, “I had been working on remaining calm in new environments” (past perfect continuous), and that would have been all right, a bit of interior monologue. Or, I could have had her say, “By the time I will have left China I will have been working on remaining calm in hundreds of new environments” (future perfect continuous), also as part of an interior monologue.

Author Rita Mae Brown noted in 1988, that, “unfortunately, a rash of novels in the last decade have been written in the present tense. It’s a fad and it won’t last” (p. 69). It has.

She acknowledges that, “there are good reasons for writing in the past tense. The first is familiarity. Every story we’ve read since The Iliad has been written in past tense. Don’t argue with thousands of years of success. The second reason is that the reader needs and wants distance from the story. This safety zone, provided by the past tense, allows the reader eventually to open up for the emotional impact of the story. . . ” (p. 69).

I like the present tense and have used it in my nonfiction books to gain the immediacy that Brown described. However, I also use dialogue frequently, and that is one way to “capture immediacy” (p. 70). Still, writes Brown, “The sacrifices of tradition, reader identification, and technical smoothness don’t justify the use of present tense” (p. 70).

Whatever you choose, go for consistency unless you have a special reason for using another tense and concentrate on letting the reader know that you’ve not just made an error.

Active and Passive Verbs and Constructions

This next problem with verbs is more vexing than pacing and tenses. It is a problem of agency, or the identification of who/what acts upon the verb.

The active voice is preferred in most writing.

Even the preceding sentence illustrates part of the problem. WHO prefers the active voice? Better sentences include

Writers prefer the active voice in their writing.

Readers prefer the active voice in what they’re reading.

Editors prefer the active voice when they copyedit writing for publishing.

Everybody prefers the active voice in writing.

No one prefers the active voice in writing.

The Romulans prefer the active voice in their writing.

The examples above demonstrate that the problem can be called a problem of

Deleted Agents

Obscured Agents

Generic Agents

Irresponsible Liars

With so many possible agents (those who do the work of the verb), this problem seems to me a problem of obscured agents. It could be the other problems, as well, including a deliberate lie.

The bottom line in word choice and syntax (the words of the sentence) is choosing an ACTIVE versus PASSIVE verb and sentence structure. Active, of course, means that the agent is acting on the verb. Passive means that the verb seems to be acting without agency.

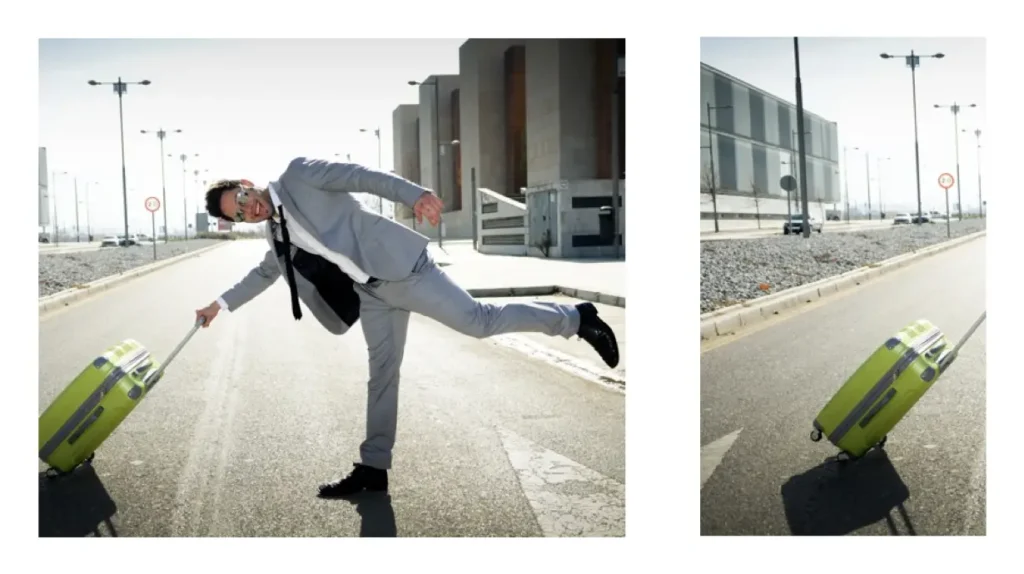

The pictures illustrate the difference. The first picture could be captioned [by whom?] as “The happy businessman pushed his suitcase to the airport parking lot.” The AGENT is the happy businessman. The picture to the left could be captioned [by whom?] as “The suitcase was pushed towards the airport parking lot.” THERE’S NO REAL AGENT IN THIS SENTENCE, unless we believe suitcases can push themselves.

Note: I have created passive sentences myself with the words “The picture could be captioned. . .” and “The picture the left could be captioned by. . . .” The active version of those sentences would be “I captioned the first picture. . .” and “I captioned the picture to the left. . . .”

Author Rita Mae Brown lists some reasons for using the passive voice

- “You don’t know the active subject or you can’t easily state that subject. Hence, ‘The store was robbed.’

- “The subject is plainly evident from the context.

- “Tact or social delicacy presents you from identifying the active subject. This also allows you or your character to pass the buck.

- The passive connects one sentence with another. ‘She rose to sing and was listened to with enthusiasm by the crowd’” (p. 272).

Here are some reasons not to use the passive voice:

- The passive voice is overused in academia. Consider “The paper was written by four esteemed scholars.” The paper did not do the writing, but who did? How do we know the writers are esteemed scholars? Is the person who wrote the sentence one of the esteemed scholars? Can we trust this sentence? Should we put readers “off” with the academic voice in a narrative, unless it fits the characters?

- The passive voice is overused in government language. Consider “The road repair blocked her driveway.” Did the road repair do the blocking? Who/what did? Does that organization or person want to conceal this action and the inconvenience one of the town’s citizens endured? Who’s responsible? Why would the responsible organization or person want to deny responsibility? Should we put readers “off” with government stiffness in a narrative, unless it fits the characters?

- When people delete the agents, they may lead those who depend on what they listen to or read to become suspicious about the truth, perhaps even cynical. They may wonder if the agent is being purposefully obscured.

- As Rita Mae Brown notes, “Another infamous trick with deleted agents is to appeal to the ‘generic person.’ Journalists do this a lot. You get this construction: ‘It is known’ or ‘It is understood’ or ‘It is thought.’ Who knows? Who understands? Who thinks? . . . The suppressed deleted agent is really, ‘All right-thinking people know’ or, closer to the truth, ‘All people who agree with me understand’” (p. 74).

Also consider that verbs and syntax are not the only ways to mask the meaning of a sentence. Brown describes how

- Adjectives occurring right before a noun can obscure meaning. Consider, “Royalty regarded the plight of citizens as excessive complaining during the French Revolution.” Who’s calling the complaining “excessive”?

- Verbs become nouns, such as in this sentence: “Deciding to delay voting led to a temporary shut-down of the government.” Who decided?

- Eliminating the person who experienced something conceals the truth, such as in this sentence, “You seem to be getting lazy.” This makes it sound as if someone other than speaker has noticed this phenomenon and the speaker is simply reporting the person(s) who perceived the laziness.

- Using evaluative words without attribution leads to sentences like this, “The research on providing safe crosswalks for children is clear.” What research? Who did it? Is it clear? Really? For everyone?

Brown cites a particularly irresponsible use of words: “When all else fails, why take responsibility? Try the flat-out lie. Here is my absolute favorite. When a reporter pointed out to Ron Ziegler, Nixon’s press secretary, that Nixon’s statements were considerably contradictory, Ziegler calmly stated before God and America that the President’s previous statements were ‘inoperative’” (p. 75).

Characteristics of Effective Word Choice

Just what is “effective word choice?” Did any of you sweat to create a paper for one of your middle school, high school, or college classes only to get it back with one of these words across the top?

This phenomenon is called THE ATTACK OF THE RED PEN (and even though I eschewed the red pen, I know I wrote some of these words on the tops of papers I returned to students). I also received my share of papers with these comments on them. Cringe-worthy, indeed. Here’s the definition of what we should have been doing better:

What follows are three sets of phrases or words that might have caused our teachers to use the red pen:

THE PROBLEM? Wordy. One word could have done the work of two or more. James Carville, a political strategist in President Bill Clinton’s election campaign, said, “It’s the economy, stupid.” In the case of word choice, the sentence might be, “It’s economy, _ _ _ .”

THE PROBLEM? Also wordy, but also a bit stuffy. Impressive in a business letter but perhaps less so in a narrative. (I confess to using the phrases or words on the left side when I want to avoid re-using a word on the right side or when I want to create a laugh.)

Consider WEEDING out the extra words or the words that do not fit the tone you are trying to set. For example, if you want to create a blithe or buoyant mood, you probably won’t want to write “due to the fact that.”

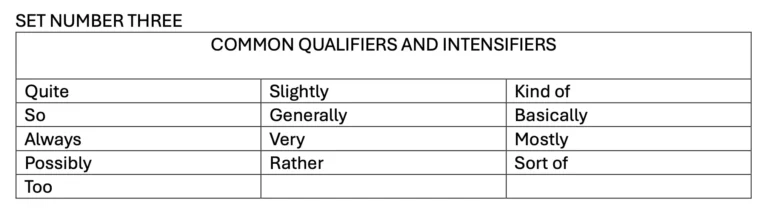

THE PROBLEM? These qualifiers are usually unnecessary. For some writers, they function like “ummmmm,” a placeholder for a better word yet to come. Omit them. Here’s a sentence that epitomizes Qualifier Overkill:

It really seemed quite possible that they basically misunderstood the plot of the entire film which essentially took away from the credibility of their critique.

Here’s the same sentence without the qualifiers (and improved in other ways, too):

The film reviewers misunderstood the plot, which took away from the credibility of their critique. (from https://www.unr.edu/writing-speaking-center/writing-speaking-resources/word-choice)

There Is/There Are

One of the best examples of wordiness is the phrase “there is” or “there are” (along with its compatriots “here is” and “here are”), which means that, in a sense, they’re the best examples of wordiness, too. These words and the word “it” can be considered dummy subjects. Consider:

There is someone on the phone for you.

VERSUS

Someone is on the phone for you.

Here are the plants Philbert ordered.

VERSUS

The plants Philbert ordered are here.

There’ll be a party after the concert.

VERSUS

The family is having a party after the concert.

It is the only activity after the concert.

VERSUS

The party is the only activity after the concert.

The only time to use “there” and “here” is when you want to establish directionality:

There’s the book I lost.

I looked for my lost shoe here.

Unless you want to establish direction, using “there” and “here” delays the reader from getting to the meaning of the sentence. Avoiding “there” and “here” will also help you avoid the decision about the verb you need:

There is my uncle and his wife.

There are my uncle and his wife.

The Pronoun Problem

Pronouns are great for avoiding repetition of nouns. However, they are problematic in many ways, so much so that I sometimes rewrite a sentence just to dodge a bullet. I corralled what I think of as the top 6 pronoun problems and present them in this chart along with some tricks (like rope tricks, just to keep the extended metaphor going) you might find helpful:

Note #1: Finally, a thought about gender and pronouns. I am in accord with current thinking about the importance of pronouns in terms of identity. As a grammarian of sorts (English teacher), I admit that I still startle when I hear or read the words “they” or “them” or “their” when I’m expecting to hear or read “her,” “him,” “she,” “he,” etc. But I am growing accustomed to the changes and believe they make our language better, bringing it into line with our cultural changes. I deeply respect the pronouns a person requests that I use.

Note #2: Note: If I liked them more, I would devote a whole blog to explain why a particular pronoun works in a particular sentence, but I find pronouns boring. I never memorized pronoun rules, but I remembered a variety of pronoun tricks. When I can’t figure out which pronoun to use, I work around the problem.

Note #3: Children’s books about pronouns are a fun way to understand how pronouns work.)

Note #4: In lieu of more ‘splainin’ about pronouns, here are some examples of pronouns that are in deep trouble in their sentences. Can you discern the problems and fix them? (Revisions follow.)

- “Me and my girlfriends threw them a party.”

- “A Secret Service member must always keep an eye on their gun.”

- “The editors and the publishers ate their lunch in silence.”

- “My grandmother was the person that I looked up to the most as a child.”

- “Everybody they insulted were unhappy with the results.”

- “Hilary gave gold chains to Marc and she.”

(Right answers: 1. My girlfriends and I threw a party for the incoming interns. 2. A Secret Service member must always keep an eye on his gun. OR A Secret Service member must always keep an eye on her gun. OR Secret Service members must always keep an eye on their guns. 3. “The editors and the publishers ate their lunches in silence.” 4. “My grandmother was the person who I looked up to the most as a child.” 5. “Everybody they insulted was unhappy with the results.” 6. “Hilary gave gold chains to Marc and her.”)

Experiment with Word Placement

Word order in English is usually simple. A subject (and its attendant words) comes first, followed by a verb (and its attendant words). Here’s an example. Actually it’s four sentences in one, but each is a subject plus a verb (in all caps) and a conjunction (bold):

The dog STARTED BARKING so the cat RAN AWAY and I COULDN’T KEEP UP, so I STOPPED.

However, word order can change meaning. Think of these classic headlines (one is often used as an example of how a headline gets a reader’s attention):

The dog bit the man.

The man bit the dog.

Here’s another:

He genuinely needs to do that.

He needs to do that genuinely.

And another:

Sentence 1: I only like non-vegetarian dishes.

Sentence 2: Only I like non-vegetarian dishes.

Sentence 3: I like only non-vegetarian dishes.

Sentence 4: I like non-vegetarian dishes only (from https://byjus.com/english/word-order/)

What’s important to us as writers is how word order can “change the spirit, meaning or fluency of a sentence” (from https://editorproof.net/on-the-importance-of-word-order-in-english)

Romeo: What light breaks from yonder window?

Romeo: What light from yonder window breaks?

Shakespeare departed from conventional word on purpose. The first question suggests something as mundane as What is that light over there? It asks for information.

The second question is full of emotion. In Act I Scene 5 he has fallen in love with her overnight and in the morning his love has grown in intensity. He thinks he has identified her window (and, perhaps, Juliet standing at it – though Shakespeare isn’t clear about that), but he doesn’t ask whose light it is. Instead, he launches into a paean, comparing her to the sun and arguing with himself about his extended metaphor. He is lovesick, and the moon becomes a threat (it might use up some of Juliet’s sun) and Juliet will become pale, like the cold moon and won’t love him or let him love her. Then he becomes reassured because of the brightness of Juliet’s twin stars – her eyes – and her cheek against which he wants to place his gloved hand. “Poignant” is the least of the words we can use to describe the emotion in this line as Shakespeare wrote it.

Inversion draws attention to meaning; however, the writer who inverts sentences too regularly faces the problem of inversion becoming common and a sentence or two written in customary word order.

So grateful are we for your welcome.

We are so grateful for your welcome.

“Let’s get there early enough to get good seats,” Jane said.

“Let’s get there early enough to get good seats,” said Jane.

With syntactic tension, the sentence builds dramatically, with the most dramatic moment coming at the end:

Crawling along the dark dungeon floor, gasping for air, hoping to find a small ray of light, the prisoner cried out. (from https://www.summitlearning.org/docs/)

Repetition is another way that word order can affect the tone, spirit and meaning of a sentence. Here is Ralph Waldo Emerson:

“What lies behind us and what lies before us are tiny compared to what lies within us.”

The repeated words do not need to be in the same sentence. Think of the words of Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream,” speech, with one sentence beginning with those four words, and leading to the same construction in the next sentence. . .and the next, until the emotional impact crests.

A variation on repetition is antithesis in which one word and its opposite are related. Think of John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address:

“Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.”

Or John Glenn’s dramatic statement as he placed the first human footprint on the moon:

“One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

Criteria for Making Effective Word Choices

George Orwell, the British author known for books of social criticism, such as 1984 and Animal Farm, prescribed some rules for choosing words.

Orwell’s Rules for Better Writing

- Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

- Never use a long word where a short one will do.

- If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

- Never use the passive where you can use the active.

- Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

These make as much sense today as they always have (and I’ve already mentioned a few of them). I certainly hold with #6.

Here’s my own list, with thanks to many others who shared their lists:

- Remember that writing is a choice and that you can and will choose every word, the order of words within every sentence, etc. What freedom that gives you. . .but what responsibility, too.

- Be precise and specific/concrete

- Convey information rather than merely take up space; be functional;

- Be aware of connotation as well as denotation; be affective as well as effective; use words that help conjure emotions

- Use the strongest words possible.

- Choose what sounds best

- Avoid jargon and slang, overused words and phrases, and obsolete words unless they are a function of character. (More about cliches in Blog 19 Special Effects)

- Minimize abbreviations and acronyms

- Allow a subtext. This means that you consciously omit something that you imagine the reader will pick up anyway. Here’s an example: Marvin gave her the evil eye, holding her in place with both eyes, and squinting to scare her. The last three words are an example of subtext; readers will probably pick up on his intent to scare her, without the writer’s help.

- Surprise the reader with unusual uses of words. Here’s an example from The Invisible Bridge by Julie Orringer: “Budapest was cobwebbed with memories. . . .” Here’s another example from Orringer: a boy remembers his mother’s sewing box as, “the round blue tin that held a minestrone of buttons.” (from https://www.writersrelief.com/word-choice-usage-writing/)

What to Do to Improve Your Word Choice

- As always, read, read, read and read some more. Absorb words that delight you, so you’ll have them always and be ready to use them in your writing and speech.

- Read aloud and listen for the sounds and rhythms, pace, and rising and dropping pitch. Do this for what you are reading as well as for your own writing.

- Use the thesaurus to expand your word library.

- Look up words – especially those you’ve selected from a thesaurus in a dictionary to make sure it is appropriate and current for its use.

- Keep a word journal. I write on whatever paper I have available and stuff the papers into a box. I go through the box when I’m looking for inspiration.

- Learn a new word every day. Truth: My family and I spend part of dinnertime learning about a word we’re unlikely to know. Often these words come from old Word-A-Day calendars. Yes, a bit geeky.

- Use new words in conversations. Try them out.

- Play word games. Bored while you’re waiting for wait staff? Play a quick game of Hangman on a napkin. Geeky, too.

Bottom line: Consider APA

In Blog #8 More Than AP: Audience, Purpose, and Attitude, I dwelt on the ultimate questions to ask about your writing:

- Who is my audience? How well am I writing for this audience?

- What is my purpose? How well do I focus on achieving my purpose through my writing?

- What is my attitude towards what I’m writing (my plot and characters; the conflict that unites plot and characters; the setting, etc.)?

- To what extent (when and how often) do I detour from attending to my audience, purpose, and the attitude I’ve taken towards my narrative? Is my detour significant? If so, what should I do about it?

I recommend that you view all your writing as persuasion, even if you are not intending to persuade anyone of anything, as you would in a persuasive essay. What you want to do is persuade your reader to believe in you and your story and to persist in reading it.

An Invitation to Become Wordstruck

The author of Wordstruck, Robert MacNeil, indulges in his love of words throughout his book. Here he revels in the language of the sea and invites you to do so too:

The author of Wordstruck, Robert MacNeil, indulges in his love of words throughout his book. Here he revels in the language of the sea and invites you to do so too:

Everybody depended on his ship coming in. They were all in the same boat, waiting till the bitter end. In everyday life, they would back and fill, or be taken down a peg or two if they didn’t know the ropes. They had to keep a weather eye open and give a stranger a wide berth if he was bearing down on them and they didn’t like the cut of his jib, because he might be armed to the teeth, at least until he showed his true colours or nailed his colours to the mast. If he spliced the mainbrace before the sun was over the yardarm, put too much grog on the rocks and down the hatch, got three sheets to the wind and keeled over, he might have to trim his sails and pour oil on troubled waters to get on an even keel, or risk being keel-hauled. If they slacked off or rested on their oars, weren’t pulling their own weight, or sailed too close to the wind, someone might lower the boom and take the wind out of their sails, forcing them to chart a new course. In the doldrums, if they didn’t make headway and were dead in the water, they might be all at sea, and long for a safe harbour, because time and tide wait for no man. If landlubbers shoved off and ventured on the high seas, come hell or high water, where it wasn’t all plain sailing, they’d have to hit the decks and haul it or be half seas over and even pooped before they could drop anchor or barge in to put their port side alongside the dock for the longshoremen to discharge cargo. If some tar listened to too much scuttlebutt and talked a lot of bilge, they might give him some leeway or tell him to pipe down or put him in the booby hatch if he and the captain were at loggerheads. If a ship was first-rate, and the captain no figurehead, he’d have her shipshape from stem to stern, so by and large she’d get a clean bill of health. Then the swab could clear the decks, stow it, lower the gangway, don his middy blouse and peajacket, and, if he wasn’t too hard up, go off on his own hook and see whether the broad-beamed lady pacing the widow’s walk still liked him or was just a fairweather friend (pages 67-8). (Image by freepik)

How many of these words or phrases from sailing have you used in your own life?

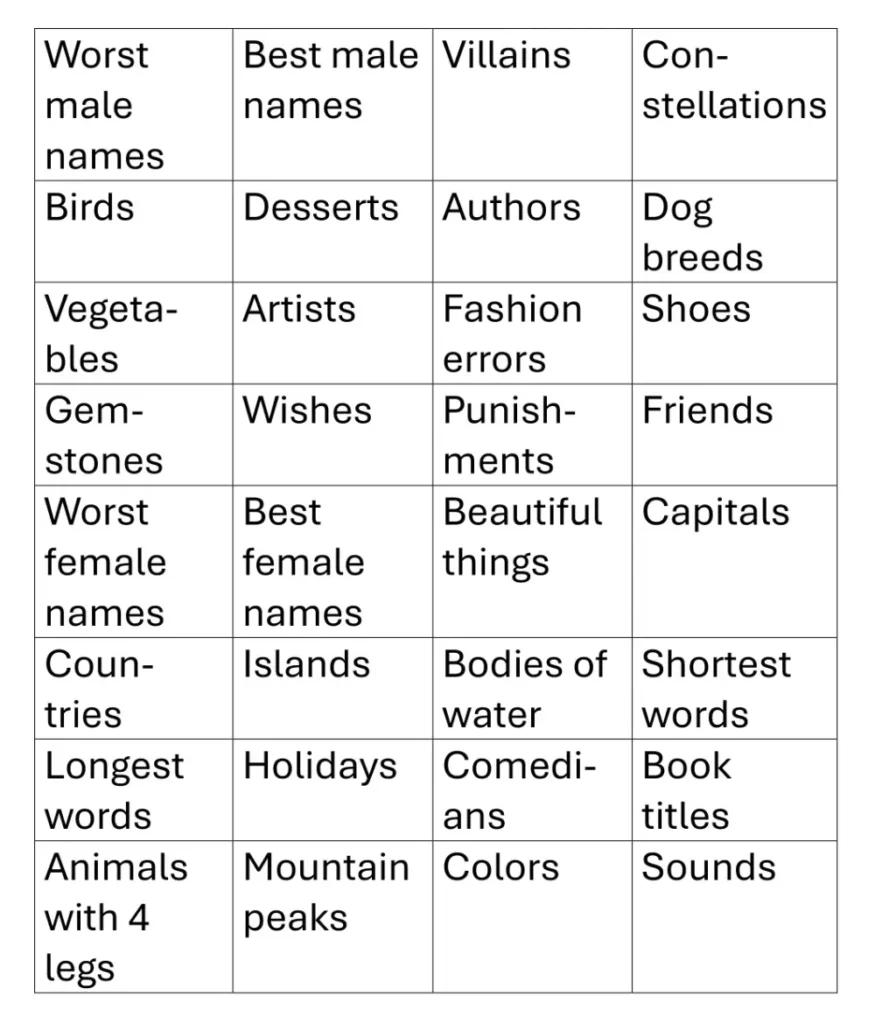

Finally, indulge in a little wordplay yourself. Delight in words that come to your mind. I get ready to sleep with a word game I usually don’t finish. I think of a category, such as the following:

Then go through the alphabet and name a word that starts with each letter and fits the category. I challenge myself to get through some tough letters, such as X (I allow eX) and Z (but often I’m snoozing by then). Have fun.