Imagine a flavorful stew. Bobbing around in a spicy broth might be chunks of meat, carrots, potatoes (not too soft), celery, onion. Perhaps, once-frozen peas or kernels of corn. Turnips (if you like them) and a few cloves of garlic. Banana slices. Cubes of toasted pumpernickel. Jellied moose nose. Coral worms and circus peanuts to intensify the taste.

Imagine a flavorful stew. Bobbing around in a spicy broth might be chunks of meat, carrots, potatoes (not too soft), celery, onion. Perhaps, once-frozen peas or kernels of corn. Turnips (if you like them) and a few cloves of garlic. Banana slices. Cubes of toasted pumpernickel. Jellied moose nose. Coral worms and circus peanuts to intensify the taste.

Wait! What? You might be trying to thwart a gag reflex after reading the last few ingredients in this “flavorful” stew. Reading a sentence stew can be as revolting. Few authors set out to write a sentence stew, but they may end up doing so for several reasons, feeling queasy as they add each ingredient.

A Sentence Stew

Paragraphs

Stew is usually served in a vessel, often a bowl. In writing, a sentence stew is usually served in a container known as a paragraph, which

- Consists of one or more sentences that are individually meaningful and structured to give the whole paragraph meaningful.

- Is unified and coherent (related to a single topic, idea, thesis or point); this is sometimes called a “controlling idea.”

- Is organized so that each sentence within the paragraph builds from or towards the whole.

- Is sufficiently developed (through details, examples, sub-topics, etc.) so that the meaning is evident.

- Emphasizes what the writer hopes the reader will experience; it has focus.

- Is separated from paragraphs before or after it through a form of punctuation called indentation.

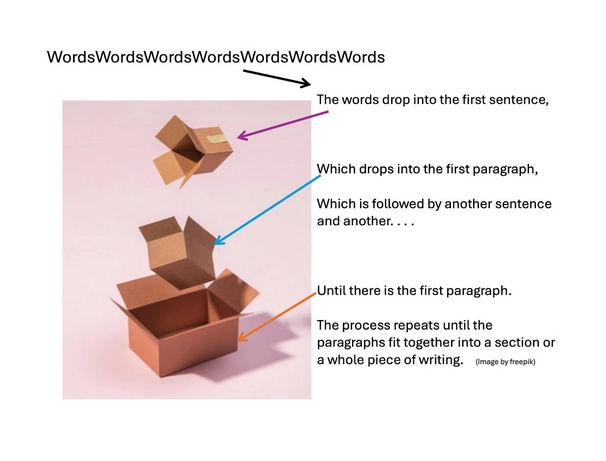

A paragraph is considered the building block of writing (although some could argue that a sentence is the building block of writing). Let’s agree: Both sentences and paragraphs are building blocks of writing. Here’s how these blocks fit together:

Some Myths About Paragraphs

Myth #1 They are more than a break in the writing. They need the characteristics in the list to be a paragraph: meaning as a whole, coherence, organization, development, emphasis. They do more than give a reader “permission to breathe” (from Writer, 2015).

Myth #2 Paragraphs cannot be a single sentence. Think of newspaper stories. They are often a single sentence (partially because the columns are so narrow that a paragraph with more than one sentence would appear to be quite long).

Myth #3 The gist (main idea, topic, idea, thesis, or point) must appear in a single sentence, either the first or last sentence in the paragraph

Myth #4 Three is the ideal number of sentences in a paragraph. Nope. Paragraphs can be any number of sentences if the result is coherent and powerful. There is something to be said about the number three. . .but that will come later.

I remember English teachers from sixth grade on drilling Myths #2, #3, and #4 into my head as Truths. I never believed in Myth #1.

A stew – a bowl or vessel – is no better than its worst ingredient(s). Reread the introduction to this blog for a good example. A paragraph is no better than its worst ingredient(s) – its sentences.

Sentence Stews Do Not A Good Paragraph Make

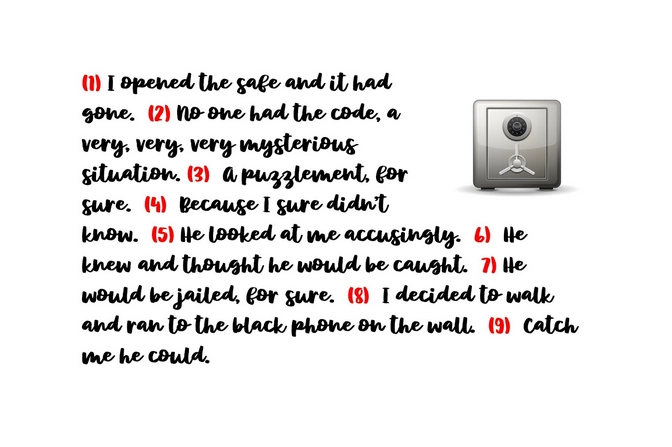

An Example of a Paragraph of Sentence Stews

You’ll see the Paragraph of Sentence Stews again, so I’ve numbered the sentences for easy reference. First, however, we’ll clean up this mess.

Deconstructing a Sentence Stew

Some ingredients in a stew may be flavorful: others may be uninviting; still others may be unappetizing. The same is true for sentences. Some add flavor. Others are ordinary. Others kill a reader’s appetite for reading.

Flavorful Sentences

One way to understand flavorful sentences is by reading (aloud if possible) a few memorable quotations:

- All the world’s a stage. And all the men and women merely players.|They have their exits and their entrances

And one man in his time plays many parts. (Shakespeare, As You Like It) - You must be the change you wish to see in the world. (Ghandi)

- All that glitters is not gold. (Versions from Aesop, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Gilbert and Sullivan, Jimmy Dorsey, Tolkien, Neil Young, Led Zeppelin, Bob Marley, Prince)

- Well done is better than well said. (Franklin)

- The only thing we have to fear is fear itself. (Franklin D. Roosevelt)

- Darkness cannot drive out darkness: only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate: only love can do that. (Martin Luther King Jr.)

- Do not go where the path may lead, go instead where there is no path and leave a trail. (Emerson)

- In the end, it’s not the years in your life that count. It’s the life in your years. (Lincoln)

- You will face many defeats in life, but never let yourself be defeated. (Angelou)

- May you live all the days of your life. (Swift)

What caught your attention as you read these quotes? I noticed that some or all the quotes

- Were dramatic, building tension from beginning to end (#1, #5, #6)

- Used repetition effectively (#4, #5, #6, #7, #8, #9)

- Displayed directness and simplicity (#2, #4, #5, #6, #7, #8, #9)

- Demanded thinking; were puzzling (#1, #8, #9, #10)

- Had no redundancy (all)

- Contrasted ideas (#3, #4, #5, #6, #7, #8, #9)

- Spoke a truth; had veracity and legitimacy; were honest (all)

- Spoke to me personally (#2, #4, #5, #6, #7, #9, #10)

You may not agree with my reactions, but that’s OK! Send me a message to let me know what made these sentences work (or not work) for you.

Flavorful sentences have some ingredients in common.

Completeness

Many people would substitute the phrase “A Complete Sentence” for the single word “Completeness.” I am content with being a heretic in the English grammar world because I don’t believe that every sentence needs to be complete, that is, with a subject (noun or pronoun) and a verb. More important to me is the reader’s understanding of the sentence, which may lack a subject or a verb or have something else wrong with it, but feels complete. What’s missing is understood.

I’m describing fragments. Historically, fragments were considered errors. I’m not yet historical, but I remember English teachers writing frag in red pen on the margins of my blue and white lined papers. I also remember correcting those derelict sentences and resubmitting my paper.

Stephen King put fragments into perspective: “If your writing consists only of fragments and floating clauses, the Grammar Police aren’t going to come and take you away. Even William Strunk, that Mussolini of rhetoric, recognized the delicious pliability of language. ‘It is an old observation,’ he writes, ‘that the best writers sometimes disregard the rules of rhetoric’” (p. 120 in On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft).

Sometimes, fragments really do need a subject or verb or both. Take these sentences, for example:

The modern sculpture outside the library.

If you consider “the modern sculpture” the subject, you need a verb. What does the modern sculpture do? Or, what is it? Correction: The modern sculpture outside the library offends some people.

You may decide that The modern sculpture outside the library lacks both subject and verb. Correction: I detest the modern sculpture outside the library.

Jumped over the last hurdle but knocked it to the ground.

This group of words is missing a subject. Who jumped over the last hurdle? The words could be the answer to a question, such as “What did Naomi do?” Mentioning Naomi in the sentence preceding this one is probably not enough to build understanding, so a Correction is needed: Naomi jumped over the last hurdle but knocked it to the ground.

Knowing he had made a mistake.

This sentence seems complete. The word he could be the subject, and had made could be the verb. However, the word knowing clouds the meaning. Who did what (knowing he had made a mistake)? Correction: Mr. Dalrymple threw his pen out the window, knowing he had made a mistake. Or: Knowing he had made a mistake, Mr. Dalrymple threw his pen out the window.

The chihuahua decked out in a red and white bandana for the parade.

This sounds like a sentence. The subject is chihuahua. What did the subject do? Decked out. Can a chihuahua deck out something? Probably not. More likely, someone decked out (dressed) the chihuahua. The words decked out. . .parade together are like an adjective; they distinguish this particular chihuahua from all other chihuahuas in the parade. This group of words needs a subject and a verb. Correction: The twins decked out the chihuahua in a red and white bandana for the parade.

To travel around the world with Max and Maxine.

This is not a sentence even though travel can be a verb, and Max and Maxine can be a subject – in another sentence, such as Max and Maxine travel around the world. To make this group of words into a sentence, however, both subject and verb are needed. Correction: I wish I could travel around the world in a canoe with Max and Maxine.

Learning the grammar that would explain the many detours writers can make to get away from the standard S + V formula for a complete sentence is almost impossible, so I recommend that the writer follow this advice:

Consider the reader’s understanding of the word group/phrase. If it feels complete enough that the reader is likely to understand it, it works – even without a subject or verb or both. If the reader is likely to be confused – for whatever reason – the writer should rewrite the group of words to make it comprehensible.

Purposeful Use of Fragments

Today’s writers use sentence fragments judiciously for the following purposes:

“Make dialogue sound more natural

“Emulate realistic thought patterns

“Convey disjointedness

“Increase pacing

“Emphasize an image.”

Again, Stephen King on fragments:

“It is possible to overuse the well-turned fragment. . .but frags can also work beautifully to streamline narration, create clear images, and create tension as well as to vary the prose line. A series of grammatically proper sentences can stiffen that line, make it less pliable. Purists hate to hear that and will deny it to their dying breath, but it’s true. Language does not always have to wear a tie and lace-up shoes. The object of fiction isn’t grammatical correctness but to make the reader welcome. . .to make him/her forget, whenever possible, that he/she is reading a story at all. The single sentence paragraph more closely resembles talk than writing, and that’s good.” (page 133-134)

[Add #4: Fragments, to the left, wrapped tightly]

You’ll see fragments in poetry and in advertising copy. You’ll see fragments in short stories and novels. You probably won’t see fragments in business letters, newspaper stories, or legal documents.

Because context is so important to readers, you’ll seldom see fragments alone. For dramatic effect, a fragment might start a paragraph or reside alone between paragraphs or even serve as a paragraph. The words and sentences that surround a fragment (context) give clues about the meaning of the fragment. Here are a few fragments along with the context in which they are embedded:

Here are a few, in context:

#1 From The Trackers: A Novel by Charles Frazier. An example of fragments in dialogue. Notice that Frazier didn’t use quote marks around what people said and only used a dash when a paragraph opens with a quote.

Eve held up two fingers to the waitress, then turned and said, Tell me, Detective, how’d you find me?

–Spoke to Donal and he mentioned you might be singing in San Francisco. I’ve spent the better part of the week searching bars and nightclubs. Finally tonight, jackpot.

–You must be exhausted. All that hard work. Though I’m sure John’s cash helped make the task at least a little bit enjoyable.

#2 From Tom Lake: A Novel by Ann Patchett

“What you need to remember is that everything’s a fix,” he told me at our little table in the corner of the very dark bar. His name was Charlie. Gray suit, a white shirt, no tie.

#3 From V is for Vengeance by Sue Grafton

She glanced at me, but by then I was scrutinizing the construction of a house robe I’d removed from the rack. She seemed to take no further notice of me. Her manner was matter-of-fact. If I hadn’t just witnessed the sleight of hand, I wouldn’t have given her another thought.

Except for this one tiny point:

Early in my career, after I had graduated from the police academy. . . .

#4 From Long Island by Colm Tóibín

Gerard and Larry and Martin were among the group who made towards him, and they set about raising him on their shoulders.

“Jimmy Farrell, sportsman of the year,” Andy shouted.

“Jimmy for the cup,” Gerard roared

Jim was resting precariously on Larry’s shoulder while Martin held his leg.

“Free drinks! Drinks on the house!” someone shouted. “Jimmy’s engaged.”

#5 From Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore: A Novel by Robin Sloan

“Yes, yes,” he says with a sigh. “I have been through this before. It is foolishness. The genius of their libraries is that they are all different. Koster in Berlin with his music. Griboyedov in Saint Petersburg with his great samovar. And here in San Francisco, the most striking difference of all.”

Concrete Language

You probably don’t want to milquetoast your writing unless you’re writing about Caspar Milquetoast, a fictional character in an old comic strip called The Timid Soul. Mr. Milquetoast was described by the creator of the strip, H. T. Webster as “the man who speaks softly and gets hit with a big stick” in contrast to Teddy Roosevelt who prided himself on his big stick diplomacy.

Mr. Milquetoast, who used bland and inoffensive language, was named after the food that was served to people with digestion issues. Milk toast (or milk sop) is toast softened in milk, invented in America around the 1840s.

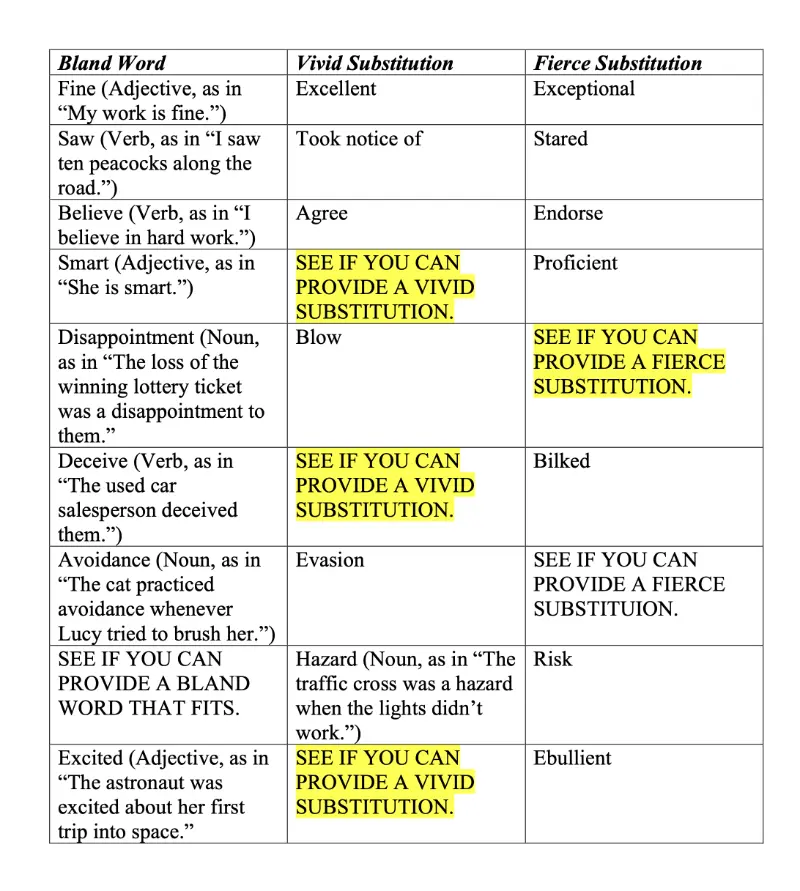

Concrete language is not bland. At its most modest, concrete language is vivid, alive, breathing. At its least modest, it is fierce, passionate, intense, powerful, and ardent. Consider these variations and add others to each category. (Image by brgfx on Freepik)

Go back to the comparison I made between food (stew) and writing (words, sentences and paragraphs). Ad writers, marketers, and salespeople must be adept at manipulating language to induce people to buy products.

Check out this website: https://www.enchantingmarketing.com/weak-words/. You’ll learn that words, sentences, and paragraphs can be bland in these ways:

- They can be chewy and tasteless. Think of really, actually, very, just, and in my opinion. They “slow down your reader without adding meaning.” Get rid of them.

- They can be stale. Think of ultimate, stunning, amazing, and awesome. “At one time these words were strong and powerful. But over time, they’ve lost their meaning—like stale bread.”

- They can be doughy. Think of them, it, these, he, was, and are. “These words have some taste but aren’t flavorsome. In moderation, they’re okay.” Note: Doughy words are pronouns rather than the specific nouns and forms of the verb to be.

- They can be low in nutrition. Think of good, nice, bad, effective, and successful. “They seem to have a meaning, but their meaning is weak.” Chewy, tasty, and low in nutrition.

What do writers (including ad writers, marketers, and salespeople) do to spice up bland language. According to the website, they spice up bland language by

Chopping off (eliminating) bland word

Chopping off (eliminating) bland word- Sprinkling in strong words

- Adding a dash of emotion

- Appealing to all the senses

- Garnishing with personality

(Image by macrovector on Freepik)

What applies to cooking seems to apply to writing, as well. Here are some bland words; I’ve contributed some vivid and fierce alternatives to some of them. What can you change or add?

Mixing It Up a Little: Variety

Long sentences and paragraphs are not necessarily better. Complex sentences and paragraphs are not necessarily better. They do not prove that you are sophisticated and erudite. Sometimes a short and direct sentence or paragraph packs more punch than a long and complex sentence or paragraph. Think of what is called an equalizer that adjusts the sound in music:

You may call it a cliché (overused word/phrase), an aphorism (expression of truth), or a proverb (advice) but it’s true for sentences that variety is the spice of life.

Imagine a paragraph in which each of five sentences is five words long, and each sentence is constructed with the commonplace Subject-Verb (S-V) combination.

The quail clutch followed behind. They were behind the mother. The mother walked in front. The clutch preceded the father. The father walked in back. This lineup kept all safe.

Well, ho-hum. The picture has more variety. It is “Just Following Mum” by Alan Vernon, who noted that behind the first baby quail are nine more all in a row, followed by Pops.

You can find two strategies for creating sentences of different length and complexity in Blog 10 Pacing: Eating Raw Rhubarb. One strategy helps writers deepen the level of development in paragraphs. The second strategy, called sentence combining, helps writers eliminate redundancies, shorten a sentence or a paragraph, and create a slightly faster pace.

Check out the Sentence Stew that opened this blog. Its structure is so random it NEEDED a bit of ho-hum.

Word Arrangement

Syntax, which means the arrangement of words and phrases, is the last of the basics for writing a flavorful sentence.

The most common arrangement is

SUBJECT + VERB (+ OJBECT )

Not all sentences have an object, so that’s why + OBJECT is in parentheses in the formula. The minimum (as I noted in the section about completeness and effective use of fragments) is SUBJECT + VERB.

Example: The children cuddled. SUBJECT + VERB

The children cuddled their dog. SUBJECT + VERB + DIRECT OBJECT

(Interesting how the meaning of the sentence changes with the addition of the direct object.)

As a reminder, either subject or verb – or both – can be omitted in a fragment. The reader must be able to trust that, if there is a fragment, the writer created a fragment intentionally; it was not just an error.

Our ultimate goal as writers is to create SENTENCE VARIETY which will lead to interesting paragraphs. We want to be flavorful, not uninviting, and – heaven forbid! – unappetizing. I’ve already described several ways of creating variety:

- Occasional fragments, including single words

- Concrete language

- Sentences of varied lengths

- Sentences of varied complexity

And now, word arrangement. Here’s a complete sentence in conventional order (subject + verb + direct objection).

The stranger, nesting inside a faded olive military-style quilted nylon jacket with gray stuffing poking through rips in the fabric and hiding all but his nose and mouth inside a frayed brown balaclava, warned me of his approach by jingling the coins in his pockets, which probably kept his hands from freezing in the near zero weather.

This is a loaded sentence. I would probably break it into two or more sentences. I would also write a shorter sentence to precede it and another one to follow it. However, this loaded sentence gives me several opportunities to play with word order. And play is what you should do. Here are five versions you can compare on several dimensions:

The Dimensions of Word Order (the ways you can adjust word order):

- The meaning of the sentence (for example, is one clearer than the others?)

- The images that connect with you

- The feelings invoked in each sentence

- How each sentence sounds (for example, melodic, jarring, piercing, soft, noisy, monotonous)

- The speed with which you read each sentence

- Where you pause in each sentence

Variations on a Sentence:

Original: The stranger, nesting inside a faded olive military-style quilted nylon jacket with gray stuffing poking through rips in the fabric and hiding all but his nose and mouth inside a frayed brown balaclava, warned me of his approach by jingling the coins in his pockets, which probably kept his hands from freezing in the near zero weather.

Version #1: I was warned by the approach of a stranger who jingled the coins in the pockets of his faded olive military-style quilted nylon jacket, its gray stuffing poking through rips in the fabric, and whose nose and mouth were hidden inside a frayed brown balaclava – all keeping him warm in the near zero weather. [The child in the picture is wearing a balaclava.]

Version #1: I was warned by the approach of a stranger who jingled the coins in the pockets of his faded olive military-style quilted nylon jacket, its gray stuffing poking through rips in the fabric, and whose nose and mouth were hidden inside a frayed brown balaclava – all keeping him warm in the near zero weather. [The child in the picture is wearing a balaclava.]

Version #2: Wearing a faded olive military-style quilted nylon jacket with gray stuffing poking through rips in the fabric and hiding all but his nose and mouth inside a frayed brown balaclava, a stranger warned me of his approach by jingling coins in his pockets, which kept his hands from freezing in the near zero weather.

Version #3: Protecting his hands from freezing in the near zero weather, the stranger warned me of his approach by jingling coins in the pockets of his faded olive military-style quilted nylon jacket with gray stuffing poking through rips in the fabric but hid all but his nose and mouth inside a frayed brown balaclava. (Image of a boy in a balaclava from freepik)

Version #4: Although gray stuffing poked through rips in his faded olive military-style nylon jacket and he wore a frayed brown balaclava that let me see only his mouth and nose, the stranger announced his approach by jingling coins in his pockets, which kept his hands from freezing in the near zero weather.

Version #5: The frayed brown balaclava hid all but his mouth and nose, and his torso was wrapped in a faded olive military-style nylon jacket, but he warned me of his approach by jingling coins in the pockets of the jacket, which also insured that he kept his hands from freezing in the near zero weather.

Comments: I got stuck by lumping together the jacket and the balaclava in the original sentence, and I had to keep both in the other versions.. The stranger did something with the jacket (put his hands into the pocket and jingled some coins), but he didn’t do anything with the balaclava. I could have gotten unstuck if I had divided the original single sentence into two sentences, one about the jacket and the other about the hat, something like this:

Protecting his hands from freezing in the near zero weather, the stranger warned me of his approach by jingling coins in the pockets of his faded olive military-style quilted nylon jacket, its gray stuffing poking through rips in the fabric. Since all but his nose and mouth were hidden behind his frayed brown balaclava, I had no idea who was advancing on me, but I knew from the sound that someone was coming.

Dividing the single sentence into two sentences gave me a chance to elaborate on the situation (I had no idea who was advancing on me, but I knew from the sound that someone was coming) which might have made the narrative more interesting.

In terms of the dimensions:

Meaning: I liked all the sentences except #1 because they took the emphasis off the person “I” and put it onto the approaching stranger. I like the meaning in #3 because I used the word “but” to establish the difference between the information “I” got through sound (jingling) but not through sight (all but nose and mouth hidden). It’s nuanced.

Images: When I moved information about how the stranger looked to the beginning of the sentence, I immediately began to focus on that image, whereas I had no image of “I.”

Feelings: Sentences #4 and #5 made me feel more anxious than the others. The ending for Sentence #2 – “which kept his hands from freezing in the near zero weather” – was lame and wiped out any feeling of suspense.

Sounds: The original sentence sounds staccato (no surprise because a first attempt is usually awkward) – bang, bang, bang, boom. The others got more melodic (but never lyrical). Sentence #3 sounds best, partially because the last few words are not as lame as in the original, and Sentences #1, #2, #4, and #5, in which the last few words descend to nothing.

Speed: Sentence #3 seems to proceed rapidly, which increases my engagement. The last few words in the original and the other sentences are so limp that the speed of my reading decreases. In fact, I found that I didn’t really want to finish those sentences. Those last few words were an add-on that didn’t work.

Pause: In all the sentences, except #1, I paused when the “I” or “me” was introduced. That’s natural. Almost any reader needs to pause to consider how the stranger and the “I” or “me” might be related. I also paused – not a good pause, however – as I read the last few words of the “add-on” sentence. Not good.

Uninviting Sentences (H-3)

Just as some ingredients in a stew are flavorful, others are uninviting (think cubes of toasted pumpernickel), and some are downright unappetizing (think jellied moose nose).

Here are three ingredients you probably want to consider before throwing them into your sentence stew:

Pronoun References

Adverbs

Passive Construction

Pronoun References

I’ve discussed pronouns in Blog #17 Words, Words, Words – I’m So Sick of Words, so I’ll just summarize how pronouns can keep a sentence from being flavorful.The problem with pronouns is that they can slow a reader down, perhaps bring the reader to a stop. (Image by wirestock on Freepik)

I’ve discussed pronouns in Blog #17 Words, Words, Words – I’m So Sick of Words, so I’ll just summarize how pronouns can keep a sentence from being flavorful.The problem with pronouns is that they can slow a reader down, perhaps bring the reader to a stop. (Image by wirestock on Freepik)

The problem is not with the pronouns themselves – they’re fine and they help writers avoid repeating nouns:

Betsy showed Betsy’s work to the assembled artists.

Betsy showed her work to the assembled artists.

The problem is that the nouns to which they refer (such as Betsy)

- may be distant

- come after the pronoun that replaces the noun

- or be missing entirely.

Let’s stay with Betsy.

Given Sentence: Betsy showed her work to them.

The Problems: #1 Who is her? Whose work is Betsy showing? Her own work or the work of someone else? #2 Who is them? Who has assembled to see the work?

Let’s say that Betsy is showing someone else’s work, perhaps Amira’s work. A good writer can fix the problem in a couple of ways:

The Solutions to her:

Add the noun before the given sentence:

#1 Amira shared her latest paintings with Betsy. Later Betsy showed Amira’s work to them. (TWO sentences)

OR #2 After Amira shared her latest paintings with Betsy, Betsy showed Amira’s work to them. (ONE sentence but Betsy is used twice)

OR #3 After Amira shared her latest paintings with Betsy, she showed her work to them. (Same problem, but Betsy is not repeated.)

OR #4 Amira shared her latest paintings with Betsy who showed her work to them. (This is the best because the pronoun who comes right after Betsy, so the reader knows that Betsy is showing Amira’s work to the assembled artists.

Adverbs

I discussed adverbs in Blog 14 You Don’t Say. Blog 14 is about dialogue as a way of creating character, but what I wrote in that blog applies in this blog, as well. I wrote, “Adverbs are normally useful to a writer (in moderation, of course, and appropriate to the plot and characters), but adverbs are usually anathema when attached to a tag.” A tag in dialogue is the “he said,” “she said” part: the attribution of the quote to someone or something.

I noted that Stephen King does a great job poking fun at adverbs that are a part of a tag. “Such dialogue attributions are sometimes known as ‘Swifties,’ after Tom Swift, the brave inventor-hero in a series of boys’ adventure books written by Victor Appleton II” (p. 126).

I noted that Stephen King does a great job poking fun at adverbs that are a part of a tag. “Such dialogue attributions are sometimes known as ‘Swifties,’ after Tom Swift, the brave inventor-hero in a series of boys’ adventure books written by Victor Appleton II” (p. 126).

Note: I am not referring to the fans of Taylor Swift.

Here are some examples of adverb Swifties:

“Welcome to my tomb,” Tom said cryptically.

“I’m a softball player,” Tom said underhandedly.

Clearly, you’ll want to avoid adverb Swifties, but the important advice in this blog is to use adverbs IN MODERATION. . . .AND APPROPRIATE TO THE PLOT AND CHARACTERS. (Yes, clearly is an adverb.)

Clearly, you’ll want to avoid adverb Swifties, but the important advice in this blog is to use adverbs IN MODERATION. . . .AND APPROPRIATE TO THE PLOT AND CHARACTERS. (Yes, clearly is an adverb.)

Adverbs are useful because they modify three types of words: verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs:

Modifying a Verb: He yelled loudly.

Modifying an Adjective: The car was really beautiful/The really beautiful

Modifying Another Adverb: The actor exited the stage too quickly.

People recognize an adverb when they see an -ly at the end. However, many adverbs do not end in -ly. To identify adverbs, slowly read aloud your work and circle every word you think is an adverb. Ask yourself: What does this word do in this sentence? Chances are, you’ll say that does one of these three things:

- Tells how, when or where about a verb (as in loudly, which tells how he yelled)

- Emphasizes an adjective (as in really beautiful)

- Emphasizes another adverb (as in too quickly)

The problem with the examples I’ve given is that the adverbs (in bold) don’t add much to the meaning of the sentence:

- Yelling is already loud, so why would you want to add the word loudly?

- What’s the difference between a beautiful car and a really beautiful car?

- What kind of exit is too quickly? How does it different from quickly?

The most useless adverbs are very, truly, really, definitely, too, extremely, quite, actually, completely. A writer may think that these adverbs emphasize the importance of the verb, adjective, or another adverb, but they are so overused that readers skip right over them. Did you skip over the word “so” in the sentence preceding this one? “So” is an example of an overused adverb.

They are relatively easy to use, as I proved by slipping in the word relatively. But they merely reiterate what’s already obvious. (Two more: merely and already.) Consider several drawbacks:

They may clutter the writing.

They contribute to wordiness.

They are redundant.

Some consider adverbs as a sign of lazy writing; rather than seeking the perfect word, a writer may dump an adverb into a sentence.

Experienced authors eschew adverbs and advise others to do so as well:

Stephen King: “I believe the road to hell is paved with adverbs.”

Annie Dillard: “Adverbs are a sign that you’ve used the wrong verb.”

Anton Chekhov: “When you read proof take out adjectives and adverbs wherever you can.”

Mark Twain: “I am dead to adverbs.”

Graham Greene: “The beastly adverb – far more damaging to a writer than an adjective.”

A.B. Guthrie, Jr.: “The adjective is the enemy of the noun and the adverb the enemy of damn near everything else. Nouns and verbs are the guts of the language.”

Mary Oliver: “Every adjective and adverb is worth five cents. Every verb is worth fifty cents.”

Some writers worry about placement of adverbs. The obvious solution to a placement problem is to avoid using an adverb in the first place. But here is an example of a misplaced adverb: They quickly walked to the mall. If you are going to use an adverb to modify a verb, it should be placed after the verb: They walked quickly to the mall. Of course, you can ditch the adverb and write a better verb: They rushed to the mall.

Some writers claim that adverbs tell readers too much by directing readers to qualities that they should recognize themselves, based on the nouns and verbs in the sentence. They limit readers to the “how,” “when,” and “where” as determined by the author. They tell rather than show the reader. (Sometimes that’s what authors should do for readers, but showing is usually much better than telling.)

Some writers worry about how many adverbs they should use. Here are some answers:

- No more than one adverb for every 300 words. (Source unknown)

- Eighty adverbs for every 10,000 words. (Attributed to the sparsest of writers, Hemingway)

- One hundred forty per 10,000 words. (Stephen King is said to have quipped about J. K. Rowling, “Ms. Rowling seems to have never met one [an adverb] she didn’t like”)

Note: An early edition of Microsoft Word sometimes underlined adverbs and the words they modified and recommended that the adverb be removed.

Passive Construction

The active voice is preferred in most writing.

In the crime above, you (the reader) probably understand that the active voice is better, but you don’t know WHO prefers that voice instead of the passive voice. Is it the person next to you on the bus? Your ninth grade English teacher? A fellow writer? A group of readers who wrote to complain about your use of the passive voice? The editor of one of your books? This sentence is contradictory. It lauds the active voice in a sentence written in the passive voice. Shame. And off to jail with me! Mine is a rather harmless error (though inexcusable for a writer who purports to write about writing). Others have maintained that writing passive sentences can be a deliberate act of obfuscation. In fact, passive sentences may delete or obscure the agent on purpose. Author Rita Mae Brown discussed some reasons writers might use the passive voice in her book Starting From Scratch: A Different Kind of Writers’ Manual” (pp. 74-5):- In the sentence, “The store was robbed,” the reader doesn’t know who robbed the store.

- Perhaps the writer doesn’t know who committed the robbery and could only write a passive sentence.

- Perhaps the writer knows the robber but wants to prevent readers from pillorying the thief.

- Perhaps the writer fears revenge from the thief.

- Perhaps the writer omits the thief’s name because it is the mayor. Perhaps the writer wants to protect the mayor’s reputation, or the newspaper has a policy about naming officials involved in a crime, or the mayor has slipped the writer a wad of cash.

- A university publishes a paper that begins with the sentence, “This paper was written by four esteemed scholars.”

- The paper did not do the writing, but who did?

- How does the reader know the writers are esteemed scholars?

- Is the phrase just another example of university jargon?

- Is the person who wrote the sentence one of the esteemed scholars?

- Is the real author being concealed for some reason?

- Is there something shady about the report?

- Mr. Watson finds a notice hanging on his front door: “On Tuesday, Endsly Street will be repaved from noon until 5:00 PM.” Mr. Watson wants to learn much more about the paving work.

- Who is doing the repaving? The city? County? State? Someone else?

- Has someone erred by posting the notice without mentioning the responsible entity and a contact number?

- Rather than an error, is this omission purposeful? Did the government unit authorizing the repaving give advance notice of the work? Did it hold an open discussion about the necessity of repaving?

- Does the government unit have a plan for what the neighborhood will do during and after the repair? What about emergencies?

- What if the repaving is not done correctly? “Who ya gonna call?”

- Is this just another example of government language? Is this a way the government shields itself from criticism?

- Lauren overheard the barista say to the customer at the counter, “It is well known that people follow delivery trucks to steal whatever their drivers are leaving at someone’s front door.” She wondered

- Has the barista experienced this problem? Is she the only one talking about it?

- If she hasn’t experienced it herself, has she heard from others that they have had packages stolen from outside their homes? Who are these people? How reputable are they? How many are there? Is the number of reports high enough to make something “well known”?

- Are people spreading the news about these thefts for any particular reason?

- Should Lauren do anything to challenge the barista, reassure the customer, or put a camera outside her own front door?

Unappetizing Sentences

Sometimes sentences are flavorful; sometimes they are uninviting. They can also be downright unappetizing, such as when

- They reek with redundancies

- They lack parallelism

Redundancy

Repetition is different from redundancy. (Image by juicyfish on Freepik)

Repetition is different from redundancy. (Image by juicyfish on Freepik)

Repetition is purposeful, one way a writer drives home a point, creates a sense of urgency, or convinces readers.

Redundancy lacks purpose. It can occur when a writer pairs one word with another, and 1) only one of the words was needed; or 2) neither word works, and the writer should seek a different word; or 3) the writer repeats synonymous words, hoping that one will convey the writer’s intention.

Martin Luther King is among the many great speakers who use repetition effectively. Confident that he has the right word, King uses it to begin several statements in a row, as in this quote:

Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quick sands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.

The right word or phrase may be repeated as King did in a row of sentences. In other situations, the right word might be spread out in a paragraph or section.

A writer using redundancies may attach a superfluous word to a word that seems unable to convey meaning. Here’s an example: “The teacher told them to write down the classroom rules.” The word down is redundant because write contains the idea of down within it.

Can you find the ten words/phrases that are redundant in this passage?

“I woke up early because I had a meeting at 7 a.m. this morning. It is a good thing I live in close proximity to my office, so I didn’t have to leave too early. I stopped at Starbucks, which is in the immediate vicinity of where I work. I am missed if I don’t show up at a meeting, since the company is small in size. This meeting was about our latest project. We made a decision to collaborate together on it for the purpose of getting a variety of different ideas. The creativity of this company is the reason why I took the job. It is a great job, but at this point in time I haven’t gotten a raise as yet.”

Answers:

- “7 a.m. is the morning, so we don’t need to also write this morning.

- “Close proximity? Close is enough.

- “Immediate vicinity means near.

- “We know small refers to size, so we don’t need to use small in size.

- “Made a decision can be replaced by decided. This redundancy is called a “nominalization,” which means turning a verb into a noun, thus adding more words.

- “You cannot collaborate unless you work together, so together is redundant with collaborate.

- “Variety implies that the ideas will be different, so we don’t need both words.

- “We can use is the reason or we can use is why, but we don’t need to use is the reason why.

- “At this point in time is not necessary at all. You are obviously referring to the present.

- “You don’t need as yet. Yet is enough.” (https://big words101.com/2014/blog/oops-i-did-it-again-redundancy -in-writing/)

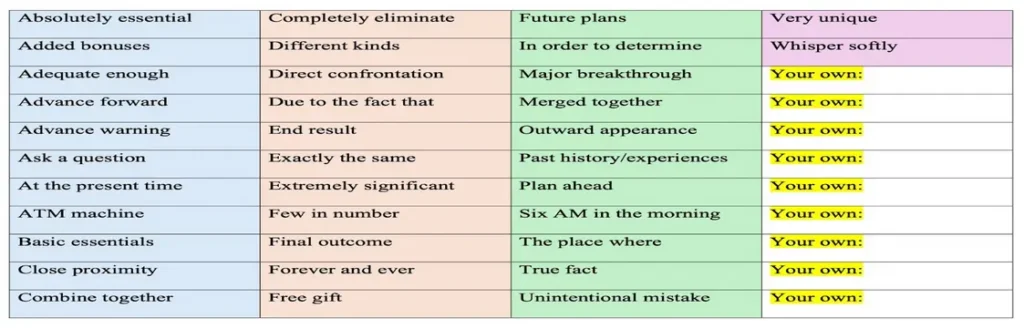

Add Your Own Examples of a Redundancies to this Partial List of Common Redundancies

Redundancy also occurs when a writer is searching for the exact word or phrase and may use several possibilities in a row hoping that one of them will be right for the reader. Here are examples of “fishing for the right word”:

She wasn’t just lazy; she was indolent, sluggish, and lethargic.

The drywaller was efficient, nimble in his drywalling work.

When the horse jumped or sailed over the fence, we all cheered.

A double negative is a special case of redundancy. Here are some examples:

- You cannot go nowhere tonight.

- I haven’t hardly thought about what gift to buy.

- They weren’t unhappy with the movie, just bored to death.

- My Uncle Joe won’t back no cake for the party.

Each sentence has an adverb that makes the verb negative. These are in bold type in the sentences: #1: verb can + adverb not, #2 a contraction of have not (haven’t), #3 a contraction of were not (weren’t), and #4 a contraction of the verb will + the adverb not (won’t).

The first two sentences have a second negative adverb: nowhere, hardly.

The third sentence has an adjective happy which is made negative with the prefix un.

The fourth sentence has the noun cake (as a direct object, it receives the action of being baked – or not!).

- Not + nowhere = two negatives. If you take out either one, the sentence becomes positive (though a little awkward):

- You cannot go anywhere tonight. (The better of the two)

- You can go nowhere tonight. (Awkward)

- Have not + hardly = two negatives. If you take out either one, the sentence becomes positive:

- I have hardly thought about what gift to buy.

- I haven’t thought about what gift to buy.

- Were not + un = two negatives. If you take out either one, the sentence becomes positive (though a little awkward):

- They were unhappy with the movie, just bored to death. (Awkward)

- They weren’t happy with the movie, just bored to death. (Possibly awkward)

- Will not + no = two negatives. If you take out either one, the sentence becomes positive (one a little awkward):

- My Uncle Joe won’t bake a cake for the party.

- My Uncle Joe will bake no cake for the party..

People sometimes construct double negatives because they think an extra negative will emphasize the negativity. You may find that a character you’re writing about would use a double negative in that way. As always, the purposeful use of something considered “non-standard” is acceptable. (See Blog #16 I Can See Clearly Now: Revising and Editing, especially the part “Rules That Rule Editing” for more information about SAE or Standard American English).

Parallelism

This can be called THE PROBLEM OF THE TRAIN TRACKS.

Imagine what would happen if one of the tracks angled away from the other, just a foot perhaps, before coming back into line. Equivalent to a single word that is angled the wrong way in a sentence.

Sentences go awry when they lack parallelism. Here are some examples of that problem, with a possible correction below each one:

- I enjoy watching movies and exercise.

I enjoy watching movies and exercising. - The women went to a soccer game, the local coffee shop, and playing video games.

The women went to a soccer game, the local coffee shop, and an amusement court. - The astronaut picked up the hammer and hits the faulty door latch.

The astronaut picked up the hammer and hit the faulty door latch. - Cats are kind, caring, and like to play.

- Cats are kind, caring and playful.

- The candidate is determined, talented, and naturally leads.

The candidate is determined, talented, and a natural leader. - “I came, I saw, and they were conquered.” (after Julius Caesar)

“I came, I saw, and I conquered.” - Zaire played tennis but pickle ball was enjoyed by Ashanti.

Zaire played tennis, but Ashanti enjoyed pickle ball. - Even more than lunch, I had a nice cold iced tea.

Even more than lunch, I enjoyed a nice cold iced tea.

In contrast, here are some examples of sentences that have parallelism:

- “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.” (Saying)

- “I came, I saw, I conquered.” (Julius Caesar)

- “Easy come, easy go.” (Saying)

- “I think, therefore I am.” (Descartes)

- “You can’t have your cake and eat it too.” (Saying)

- “Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.” (John F. Kennedy)

- “I don’t want to live on in my work. I want to live on in my apartment.” (Woody Allen)

- “My fellow citizens: I stand her today humbled by the task before us, grateful for the trust you have bestowed, mindful of the sacrifices borne by our ancestors (Barack Obama)

Imagine how trains would become snarled if these four train tracks were not parallel.

That’s what happens when sentences get snarled by words and phrases that are not parallel. This means they do not have the same grammatical structure. The problem applies to

- Verbs (especially gerunds with an -ing ending and infinitives after the word to)

Example: Cats are kind, caring, and like to play.

Problem: Regular verb + -ing verb (which is OK) + to verb

Fix: Cats are kind, caring, and playful.

- Nouns and pronouns (especially plural and singular)

Example: The home carpenter requires tools, such as a hammer and screwdrivers.

Problem: The nouns are tools (plural), hammer (singular), and screwdrivers (plural)

Fix: The home carpenter requires tools, such as hammers and screwdrivers.

Example: The businessman shared their new computer program

Problem: The noun is singular. The pronoun is plural. (Perhaps the businessman shared what a group of people, including him, had done, but that’s not clear.)

Fix: The business shared his new computer program. OR The businessman shared the new computer program he and his colleagues had developed. - Adverbs and adjectives

Example: When Elway makes a mistake, he feels frustration and angry.

Problem: Frustration is a noun (think of it as “the frustration” and angry is an adjective (you couldn’t say “the angry”).

Fix: When Elway makes a mistake, he feels frustrated and angry. OR When Elway makes a mistake, he feels frustration and anger.

- Lists

Example: Belle had deadlines on the same day for five parts of her landscape architecture project:

- A master plan of the garden

- A section cut

- Finishing the narrative

- A plant palette

- To put everything in order

Problem: All but two of the items in the list are parallel. They begin with a noun (the project). Another item begins with an -ing verb form (finishing) used as a noun and known as a gerund. The last item begins with a verb + to be (an infinitive) used as a noun.

Problem: All but two of the items in the list are parallel. They begin with a noun (the project). Another item begins with an -ing verb form (finishing) used as a noun and known as a gerund. The last item begins with a verb + to be (an infinitive) used as a noun.

Fix:

- A master plan of the garden

- A section cut

- A completed narrative

- A plant palette

- A website with all the pieces in order

Definition of Parallelism

When words, phrases, or clauses all have the same grammatical structure. The elements match.

Lack of parallelism feels awkward and unbalanced. It disrupts the rhythm and flow of a sentence. Readers usually slow down when they encounter a single sentence that is not parallel and read even slower when several sentences within a paragraph are not parallel. Sometimes they come to a stop to work on the meaning, even try to correct a sentence in their own minds. If they can’t, they’ll skip the awkward sentence and hope they haven’t missed something important. Of course, authors don’t want to write sentences or paragraphs that aren’t important.

Qualities of Good Sentences

Consider these qualities of good sentences. They

- Are complete in meaning, even if it not grammatically (that is, with a subject and verb.

- Flow. The pace is effective for the meaning. They have a cadence and a rhythm that make them a pleasure to read. Though prose, they can sometimes seem like poetry.

- Use words that are pleasing (they please you as writer and are likely to please the reader).

- Are simple, but elaborate enough that they evoke a mood, paint a picture, drive the plot sufficiently, and contribute to the development of character(s). They appeal to the senses.

- Are in the active (rather than passive) voice.

- Are concrete; if abstract, they are elaborated on with concrete details.

- Are parallel.

- Have no useless or distracting adverbs.

- Have words arranged in each sentence to fit the audience and purpose and convey the attitude you want.

- Vary word order to avoid monotony and emphasize what the reader needs to know. Ensure that sentences attract readers by beginning in a variety of ways.

- Are short – just a few words long – to break up a string of long sentences (consider writing a short sentence after three or four long sentences).

- Provide pronouns with the nouns they reference nearby, preferably in advance of the pronoun.

- Are not redundant but use repetition effectively.

- Follow conventional usage and punctuation rules unless they are inappropriate for the narrative.

- Are as streamlined as possible. You have trimmed the fat in each paragraph by reading the sentences aloud as you wrote them, and then omitting one of two words, and read them aloud again to see how well the skinnier sentences work.

Techniques for Writing Flavorful Sentences

You can create better sentences by

- Writing other things – letters, jokes, petitions, journal entries – to keep your writing mind and hand flexible.

- Reading compulsively. Notice the strategies used by the author you’re reading.

- Writing with your reader in mind.

- Remembering the reason you’re writing (your purpose).

- Keeping your attitude intact as you write (how you feel about what you’re writing).

- Showing more than you’re telling.

Thinking in threes. The Rule of Three maintains that the number three is the lowest figure that can be used to form a pattern in our minds. Remembering things in threes is easier than remembering things other sized groups. (Image by freepik)

Thinking in threes. The Rule of Three maintains that the number three is the lowest figure that can be used to form a pattern in our minds. Remembering things in threes is easier than remembering things other sized groups. (Image by freepik)- Tracing your verbs, not only for tense but for action (showing).

- Tracking other words that you tend to repeat.

- Identifying your crutches, the tendencies as a writer that you’d like to decrease or discard completely.

- Being willing to write a single sentence several ways. Read it aloud – slowly – and listen carefully. Which sentences work best for you (and are likely to work for the reader)?

- Accepting that writing sentences is hard work.

A Chance to Practice

Remember the paragraph about the safe at the beginning of this blog? Here it is again. Use what you’ve learned since reading that (awful) paragraph to revise it. I have provided in parentheses one way to revise each sentence as well as one or more reasons for the revision.

Remember the paragraph about the safe at the beginning of this blog? Here it is again. Use what you’ve learned since reading that (awful) paragraph to revise it. I have provided in parentheses one way to revise each sentence as well as one or more reasons for the revision.

(1) I opened the safe and it had gone.

The problem in this sentence is the word “it” which has only one noun it could stand for: “safe.” But that doesn’t make sense. How can the main character open the safe if the safe is gone? Here’s a revision: (I opened the safe but found that the package I had hidden in it was gone.)

(2) No one had the code, a very, very, very mysterious situation.

The first problem in this sentence is “no one.” The main character opened the safe so, obviously, this person has the code. The sentence should have started with “Since I was the only one who had the code.” The second problem is the blandness of the adjectives preceding “mysterious situation.” Even one “very” is bland [chewy, tasty, and low in nutrition]. But three? The third problem is redundancy. Fourth, what words does “a. . . mysterious situation” reference? The fact that no one – but the “I” in the previous sentence – knows the code? Or the whole situation: 1) finding nothing in the safe which 2) had to be opened by someone which resulted in 3) someone taking the package? Here’s a revision: Since I thought I was the only one who had the code, I was mystified by who else had it, probably used it, and may have taken the package.)

(3) A puzzlement, for sure.

(I’d leave this set of words as it is, even though it is a fragment (lacking both a subject and verb). If could become a sentence if it were rewritten as “It is a puzzlement, for sure” or “I am puzzled by this.” However, something else mars this phrase; the word “puzzlement” doesn’t add much (if anything) to the meaning already established by the word “mysterious” in the second sentence. I’d replace “puzzlement” with a word that adds meaning, such as “delinquency” so that the reader would consider the law-breaking aspect of stealing something from a safe. And, if I wanted to emphasize the results of a delinquency, I’d bring in the possibility of jail time from the seventh sentence: A delinquency that could probably lead to jail time.)

(4) Because I sure didn’t know.

(This is not only a fragment but a rather uninteresting one. The word “because” is a connecting word. It needs something in front of it to connect to the words following it. Perhaps the phrase before “because” could be “I shook my head.” The whole sentence would be “I shook my head because I didn’t know.” However, it is bland, chewy, tasty, and low in nutrition. I’d omit it unless the main character saw the person who opened the safe when the “I shook my head.” Then, the sentence would do something.)

(5) He looked at me accusingly.

(Much is missing here. Who is standing there? How did the main character spot the person standing there? The change to the fourth sentence could accomplish the connection. What details could be added to “He” so the reader could see more than the fact that this person is male? And that brings us to the major problem in this sentence, the adverb “accusingly.” What does “accusingly” look like? I might write this: When I shook my head in puzzlement, I happened to spot someone in a wrinkled khaki overcoat in the corner who slowly turned to me with his fists up, eyes aimed at me, and mouth contorted into a sneer. Notice that I’ve rescued the word “puzzlement” and combined the idea from the fourth sentence with this sentence, expanded to show, not tell.

(6) He knew and thought he would be caught.

(The most obvious problem in this sentence is redundancy: knew and thought. The redundancy suggests that the writer could not decide on just one verb so gave the reader two to choose from. But the real problem is telling rather than showing. Why does the main character decide the safebreaker is thinking about being caught? My solution to the first problem is dialogue: “You think I’m going to be caught, don’t you?” the trench-coated man said. My solution to the second is description: He scanned the room, moving only his eyes, and checked each doorway up and down, left and right, making sure the door was flush to the frame. Then he fixed his eyes on each door’s handle before moving on. He froze when he came to the open safe and then bent his knees as if preparing to run.)

(7) He would be jailed, for sure.

(Who’s thinking this? The major character or the trench-coated intruder? In a sense, the answer doesn’t matter. It is implied in the sixth sentence. Being caught for burglary usually means some jail time. Another problem is the phrase, “for sure.” The assertion that he will be jailed doesn’t need to be padded with “for sure.” I addressed the problem by using A delinquency that could probably lead to jail time as my third sentence.

(8) I decided to walk and ran to the black phone on the wall.

(Many problems in this sentence, including its beginning, “I decided.” When does he decide? How do we know he is deciding? Writers must assume that a character who does something has decided to do it (voluntarily or involuntarily). We don’t need to be told that a character decided to move. What we don’t know is why. That’s vital. Last thing we knew, the trench-coated man was looking as if he would run. Perhaps the main character realizes the man might run to him with fists raised. The verbs don’t work at all. Is he both walking and running? Does he walk first and then run because he is scared? The verbs are not parallel. “Walk” and “run” go together. “Walk and “ran” do not go together (unless a sequence is intended). The pairing with “I decided” doesn’t work either: “I decided to walk” doesn’t go with “I decided to ran.” Here’s a possible rewrite: Seeing the man launch himself towards me, I dashed to the black phone on the wall

(9) Catch me he could.

(Yoda could say this. It’s technically correct, but its words are obviously not in the order most people would use. It’s comparable to Yoda’s “Patience you must have.” Yoda’s phrasing draws attention to the wisdom of his words and often makes the listener chuckle. You can use this phrasing if it’s appropriate to the purpose and audience – and especially to the attitude the writer has taken and wants the reader to take. Perhaps, the sentence could be rewritten: As I put my index finger in the holes in the dial of the phone, one at a time, I whispered to myself, ‘He could catch me. He could catch me.”)

And then I decided to add a final sentence – sort of a zinger to bring the reader back to the story: When I felt his hand on my shoulder, I pushed my finger into the wrong hole in the dial and felt my knees give way.

Another Version of the Paragraph

This is just one revision of the paragraph from the beginning of this blog. What would you do to revise the original. . .and my revision?

I opened the safe but found that the package I had hidden in it was gone. Since I thought I was the only one who had the code, I was mystified by who else had it, probably used it, and may have taken the package. A delinquency that could probably lead to jail time. When I shook my head in puzzlement, I happened to spot someone in a wrinkled khaki overcoat in the corner who slowly turned to me with his fists up, eyes aimed at me, and mouth contorted into a sneer.

“You think I’m going to be caught, don’t you?” the trench-coated man said. He scanned the room, moving only his eyes, and checked each doorway up and down, left and right, making sure the door was flush to the frame. Then he fixed his eyes on each door’s handle before moving on. He froze when he came to the open safe and then bent his knees as if preparing to run.

Seeing the man launch himself towards me, I dashed to the black phone on the wall. As I put my index finger in the holes in the dial of the phone, one at a time, I whispered to myself, ‘He could catch me. He could catch me.”

When I felt his hand on my shoulder, I pushed my finger into the wrong hole in the dial and felt my knees give way.