Hunched over the book in his lap, a first grader read a story to his peers who were sitting in a semi-circle in front of him on a rag rug of many colors. He sat cross-legged at the edge of the rug, clearly having dressed up for this event.

I stood behind the semi-circle of students with his teacher who had invited me to visit her classroom for First Grade Features, the name of the weekly story hour the teacher had established.

Rusty had already shown me his story. Like many first graders, he had not yet mastered the alphabet, but he had stories to tell, so he used what was called “invented spelling” (see below). He moved the index finger on his left hand from left to right as he read “sentences” on the first page of the story and moved his finger from the top to the bottom of the page. Suddenly, he stopped and cried out, “Oh. I forgot. First, I got up.”

I could hardly suppress a chuckle. Young storytellers and writers wrote “bed-to-bed” stories. Rusty had forgotten to tell about getting out of bed in the morning, and nothing could happen in his story until he had gotten out of bed. So, he placed his finger on the left side of the top line on the first page and intoned, “I got up.” Then he turned the page and resumed his story.

The end of his story was, predictably, “And then I went to bed.”

WHERE TO START YOUR TEXT

You probably do not want to start a piece of fiction or nonfiction with “First, I got up” or end it with “Then I went to bed.” Although James Joyce’s Ulysses tells of one day, June 16, 1904, and it could have been a bed-to-bed story, the first line in Ulysses is

“Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead,

bearing a bowl of lather on which a razor

and a mirror lay crossed”

His last line is about 4,000 words long, ending in

“yes I said yes I will Yes.”

No bed-to-bed story for James Joyce.

INVENTED SPELLING

Young writers (ages 4, 5, and 6 usually) who know only a part of the alphabet or a few words represent everything they hear with a mark (which may look like a letter) or a drawing. They leave out anything that seems extraneous to them and substitute freely. Their marks allow them to “read” what they have written, aided by memory of what they wanted to write. Most of us could not read this:

w hd skageti and Brd t mi fend hse

Most pre-school and primary grade teachers and parents could read it:

We had spaghetti and bread at my friend’s house.

Mostly importantly, the writer herself could read it using the print cues and memory.

As they learn the alphabet and the symbols representing sounds, they add them to their repertoire of symbols. They also add whole words (especially the ones they need to tell a story) from the books they read and other children’s books. They want their books to look like the books on the shelves in their classrooms and the school and public libraries, so they do not linger very long in any of the several stages of invented spelling.

So, where do you start?

The answer is simple. You write what you need to write. Then you have permission to begin your piece there or search for it somewhere else – a few pages beyond the first page, in the middle of the piece, even at the end of the piece.

Examples of Finding the Beginning

Here are three examples of my trying to find the beginning of my novel Through the Five Genii Gate. The first one omits characters’ names and identifying information because it was written as a biography before I decided to make it into a novel and change names of people and places to fictional names.

Example #1 (one of my first drafts)

________________ was born on February 17, 1885, in ____________, Texas, a small town in west central ____________County in the center of Texas, a hard-scrabble land which was first civilized as a Santa Fe Railroad switching point. Her father, _____________, and her mother, ___________, were both 25 when they married – she a teacher and he a rancher – and they had ___________ who was nicknamed _____________ two years later, and _____________the year after that. Then, another child almost every year until there were eight, six girls and two boys. The lineup from oldest to youngest was _____________, __________, _________, _________, _________, _________, _________, and __________.

The family owned some land near ____________ in __________ Country and ran a few hundred cattle. It was not a particularly good time to be a rancher. Livestock barely survived or starved on the native forage, and it was almost impossible for ranchers to supplement their feed in any significant way. Blizzards decimated herds, cattle prices plummeted, overgrazing ruined what natural feed there was, and drought threatened even that. The Beef Trust’s Big Four – Armour, Swift, Hammond, and Morris – made it very hard for individual ranchers to sell what beef they could raise and at least break even.

(HO-HUM)

I needed to write this because I needed to know it. But I knew even as I wrote it that it would capture no readers. It was for me. At the time, I was visualizing this book as biographical fiction. Although a “bed-to-bed” (or birth-to-death) strategy might seem a natural sequence to follow when writing an autobiography or a biography, I knew this was unpublishable.

Example #2 (a much later draft, but still seen as biographical fiction)

Through the open door, ___________ could hear a horse and buggy make its way up the dirt road that led to their ranch. She looked down at her bare feet – she’d discarded her boots to mop the plank floor – and remembered that she had bunched her work dress up under the ties of her apron. She looked out. There was her fiancé, _________.

She quickly pushed shut the bottom half of the door, hoping that would prevent Mr. ____________ from seeing her bare feet.

“Miss ___________ (her last name), ________________ (her first name),” he said, doffing his hat but still sitting atop his roan. He was dressed in his good ginger-colored suit, with a vest even though it was June, and his best cowboy boots. His oiled black hair still showed comb tracks, and his black string tie was slightly askew from riding the sixteen miles from _____________________.

“Mr. __________________, well! I didn’t expect you! Did I forget an engagement?”

“Oh, no,” said _______________, dismounting. “I’ve gotten some good news that I want to share. Will you come out walking with me?” ____________ looked down at her bare feet and her faded and dirty dress, the old one she had grabbed before riding her horse, Succotash, to the old ranch house to clean it for its new tenant. She didn’t even have a dress to change into because they were all at the new house; she could only release the drab skirts of the blue flowered cotton dress and its single petticoat from the apron ties, discard the apron, and fit her feet without stockings into the short black lace-up work boots she had worn.

In a diagram of a bed-to-bed story, this incident – which ended with the gentleman jilting my main character – meant that I started my story about one-quarter of the way from her birth to her death.

Born >>>>>>>>>>This Incident>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>Death

After he has broken off their engagement, I write about an incident that happened before this one. She was nine years old, and I used the second chapter to present information about her parents, her birth, her family, and incidents before she was nine.

(STILL RATHER HO-HUM)

I still didn’t like this beginning. I did not feel it was compelling enough to tell the story of her being jilted – even though this incident forced the main character to act. My dissatisfaction had a lot to do with my uncertainty about whether I should write a biography (even a biographical novel) or a novel. When I decided to make my story into a novel – and use both first and third person – I knew I had to begin much later in my main character’s story, and I knew I would not carry the story as far as her death.

Here’s how my much, much later draft of the story looked:

Born>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> The Incident Beginning In I1937 >>> (Death)

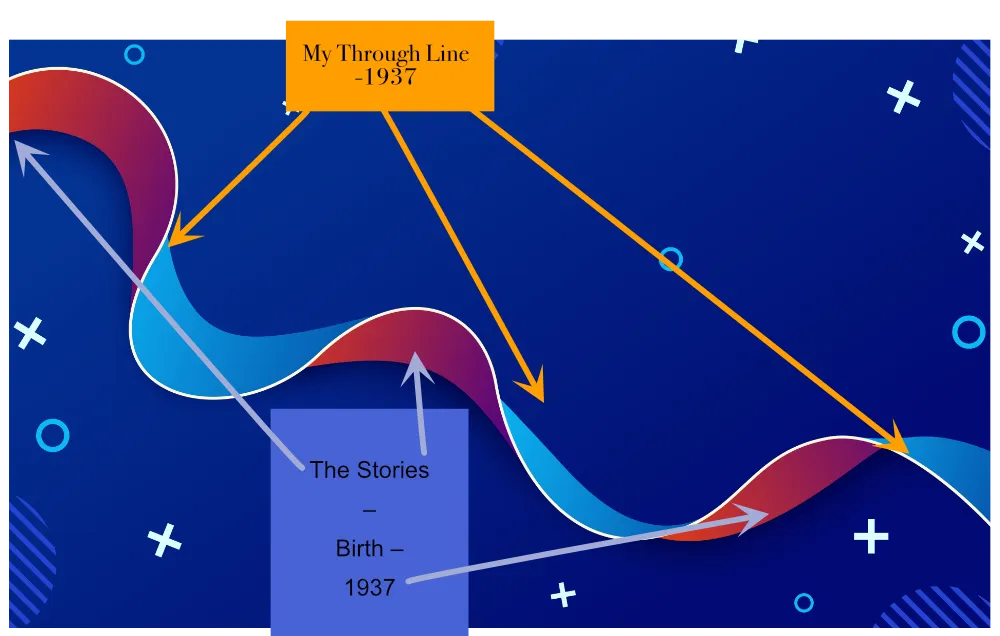

My novel focuses on part of one year (1937) of my main character’s life (in third person – my voice as author) but allows her to tell stories about the years preceding the incident (in first-person). The novel, therefore, consists of the third-person narrative about 1937, interwoven with first-person stories. Here is what emerged (much, much later, with many experimental drafts)

Example #3

(Along the Yangtze River, July 1937)

Kathryn rubbed the heel of her hand against the inside of the small porthole window on the Kiang Wo to clear a spot that would allow her a glimpse of Chungking from the Yangtze. Mr. Chu, the purser, had called out, “Missus Cam, Missy Missy, eight o’clock late! Up, up, up. Sun beat you this day!” She used the hem of her sleeve to clean the window but, still, all she could see was blackness. Or rather a smoky gray. The shaky incision the sun made through the charcoal sky illuminated ragged buildings high on what was apparently a cliff. “This is Chungking?” she murmured and turned from the porthole to wake her daughters, Emma and Lucy.

Mr. Chu had told them before lowering their bunks from the wall the night before that they would have to depart the Kiang Wo for an even smaller boat that would take them further up the Yangtze to reach Mt. Emei, one of the Four Sacred Buddhist Mountains of China, and their 1937 summer hiking and camping destination. They dressed quickly, hefted their canvas rucksacks, to which they had fastened folding beds, onto their backs, took the handles of the two duffels each had brought, and stepped outside into the narrow hallway. There, Mr. Chu waited, and hands prayerfully clasped under his chin, bowed and intoned his obituary for their plans, “Much sadness. Not go Emei. Ship stuck above. Not go back. Jap block. Go Chungking. See guvmint. He help.” He backed away from them before they could form any kind of question, so they rushed to the end of the hallway and stepped through the doorway onto the deck.

“Oh,” ten-year old Lucy noted, “it’s still night here.”

“No, silly,” her older sister Emma, fifteen, said, “It’s just smoky. See, there’s the sun,” and she pointed to the yellowish sky scratch Kathryn had seen earlier.

Their mother, leading them, suddenly stopped and – as in a comedy short – Emma bumped into her, and Lucy bumped into Emma. They lost their grip on their duffel bags, and these tumbled to the deck as the Cameron females surveyed the bedlam around them. Boats of all kinds were alongside, in front and back of them: junks with crimson sails, small river steamers like the Kiang Wo, patrol boats, flat cargo ships, a few transports with people standing in them, and even sampans with bamboo shelters arching from port to stern. Several lines of boats stretched from the shore into the middle of the river, and they jostled each other as people yelled, pointed, and ran from side to side, front to back, and back to front.

Kathryn reached for each of her daughters and said, “It looks like they all want to get to Chungking.”

“Like we do,” Emma observed quietly. But, between them and the shore, Kathryn counted eleven boats. Above the shore was a distance of at least 500 feet and then what looked to Kathryn like 500 steps that required climbing to reach the top of the cliff where the ragged buildings stood.

“Surely,” she thought, “beyond those. . .those shanties, there is civilization. We’ll be able to get a good breakfast and find the American consul. We’ll figure out what to do.”

Then, they noticed that people were getting from boat to shore by going from boat to boat, using planks that were propped on the railings of each boat or otherwise climbing up one railing and, with the help of a coolie, making a little leap to the skinny railing of the next boat, climbing down to its deck, running to the other side of the deck and repeating the maneuver.

(I’ll GO WITH THIS ONE)

What Are the Differences?

What did you notice about the three beginnings? How were they similar and different? Of course, one major difference is that the first two are still trying to be biography, albeit biographical fiction. By the time I wrote the third beginning (which was more like the twentieth in terms of all the different beginnings I wrote), I had decided that the book had to be fiction. And I had decided on two narrative voices: a third person narrative that tells the story of half a year (1937) and binds together the stories that the main character tells in first person about her life up to 1937.

You may not be able to discern this, but the beginning I wrote for the final version of the whole book was much harder to write than anything I had previously written. It required intense organization as I kept track of what was happening in 1937 and what was happening in the life of my main character. I would diagram my process as looping:

(I can well imagine that the various X and O shapes are factors or events that I contemplated including in my novel but decided not to do so!)

The only way I could manage this complicated dual storyline was by calendaring it. Here’s an example of my writing calendar for September 1937:

1937 Calendar – September

| Su | Mo | Tu | We | Th | Fr | Sa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 Upriver to Hankow | 3 continue to Hankow | 4 Board Train to Canton (12 Day Trip | |||

| 5 Train to Canton | 6 train trip cont. | 7 train trip cont. | 8 train trip cont. | 9 train trip cont. | 10 train trip cont. | 11 train trip cont. |

| 12 Train to Canton | 13 train trip cont. | 14 train trip cont. | 15 Arrive Canton; Mission; to Pearl River | 16 Arrive Hong Kong on Pearl; Board Ship | 17 Await Departure | 18 Depart on Empress of Russia (22 Day Trip) |

| 19 Stop Yokohoma | 20 Yokohoma cont. | 21 Yokohoma cont. | 22 Stop Shimonseki | 23 Sea of Japan; Dreams | 24 Comes out of Dreams Momentarily | 25 Dreams |

| 26 Comes Out of Dreams; Gets Dressed; Goes to Lunch | 27 Pacing | 28 Aboard Ship*Story of Engage (in the Calgary Room)Dawson City Café for Tea *Story of Being JiltedLunch Puzzles in the Calgary Room in PM Dinner *Story of Going Back to Ranch (in Calgary Room) | 29 Play Day | 30*Story of Family Helping (walking the deck)Lunch *Story of Going to WMUTS (Dawson City Café) |

The through line (1937) is in black. The notes in red are the stories the main character tells, in order from early in her life to 1937.

Enough about organization. The key learning for me was that the simple, straight-forward, bed-to-bed story was not going to work for me.

Here are few other insights I had as I reviewed the beginnings I wrote:

- The first two seem far away. They seem to be about characters seen from a distance.

- The third seems immediate. It is right there happening in front of the reader.

- The first seems to have answers. The second less so. The third even less so.

- The first invites very few questions, the second a few more.

- The third seems to invite lots of questions: Who is she? Why is she leaving with her children? Why are they in China? In Chungking?

- The first, especially, is fast. It goes by quickly. It covers a lot of narrative ground (1885 to about 1903) in just a few words. The third is slow, taking its time to cover only a few minutes from awakening to contemplation of first steps towards shore – and continues for several pages. The second is like the third; the first 10 minutes of the beginning also go on for several pages.

- The third is an event, in detail. It shows what is happening.

- The first is a recitation of facts. It tells. The second is somewhere between the first and third.

- The first has no immediate action, while the second and third do.

- There is no tension in the first, some in the second, and much more in the third.

I think the best reason for using the third instead of the second or first is that the third invites questions; it makes the reader want to know more.

Why didn’t I just write the third? Stephen King provides some insight into backstory.

Backstory

King defines backstory: It’s “all the stuff that happened before your tale began but which has an impact on the front story. Backstory helps define character and establishes motivation. I think it’s important to get the backstory in as quickly as possible, but it’s also important to do it with some grace.” (223)

Two questions emerge for me:

- Should a writer write as much of the backstory as possible before writing either fiction or nonfiction? Or should a writer write the backstory as the “real” writing proceeds – in other words, as needed?

- How much of the backstory should a writer share with readers, and how?

Writing Backstory

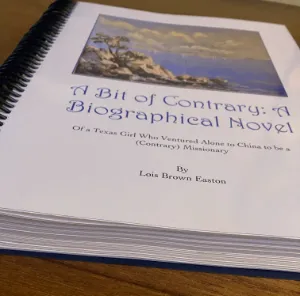

I had to write backstory before I began the novel. I think I always knew I wanted to write a novel, but I also knew I wanted it to be true to my grandmother and her life. So, I had to learn all I could from a variety of sources (research, research, research) and record everything in some kind of order. I first recorded in lists and charts what I learned from birth-to-death (or bed-to-bed) but then decided I wanted to send this information to my relatives. I wanted to make it readable and more interesting than the lists and charts would have been. I did not want to recite the facts; I wanted to create a story. Example #1 was the beginning of a recitation of some of the facts, and I could have sent it as is, but I wanted what I sent my relatives to be more like Example #2. So, I started the book I sent to relatives with the story of my main character getting jilted.

Its title was A Bit of Contrary: A Biographical Novel. Its subtitle was Of a Texas Girl Who Ventured Alone to China to be a (Contrary) Missionary. It was full of pictures. It left out nothing. It was a doorstopper:

I wrote as much of plain backstory (Example #1) as I could before I started writing this “relatives-only” version of my story (Example #2). I also developed new backstory as I discovered that I had a need to know something else. So, I did both: wrote the backstory before I wrote the novel + wrote the backstory as I went along, both within the “relatives-only” version and Through the Five Genii Gate.

It occurs to me that most authors also do both. They create as much backstory as they can before beginning to write and – as they write – discover they need additional backstory.

For example, an author may discover that a coherent backstory is simply not enough. The plot veers this way or that, the main character does something unexpected, the setting requires more description, a theme is emerging on its own. The author may need to rethink the backstory. . .or develop new parts of a backstory. . .or create a whole new backstory. What needs to happen between plot element H and plot element J? Why was the main character carrying the identity card of another person? Why did the creatures on that planet disappear? What happened to a minor character?

An author of a nonfiction essay may discover that a backstory developed to explain the premise no longer served that purpose. What’s missing? The answer to that question may lead to a redraft of the backstory and subsequent redrafting of the essay, article, or nonfiction book.

Sharing Backstory

All this thinking and writing of backstory does not necessarily mean writers need to use it in their work. Few readers – even relatives – have enough tolerance to read lots of backstory. Most writers give a little early in the book or article (kind of an introduction) and then insert it when needed as the book or article continues. Often, they sneak it in as part of dialogue or action or provocative statement.

You probably cannot get away without creating backstory for yourself. As King notes, “Even when you tell your story in [a] straightforward manner you’ll discover you can’t escape at least some backstory.” (225)

The key to sharing backstory is thinking about the reader. After you, as author, have researched or invented enough backstory to proceed with your article or script, for example, consider what your readers need.

Take a look at the following picture. If you were an author, what would you need to know to make the pictured situation plausible? How much of that information does your reader need (before, during or after the incident)? Is that information beyond or different from what you need as a writer?

King describes himself as a reader: “I’m a lot more interested in what’s going to happen than what already did. Yes, there are brilliant novels that run counter to this preference, but I like to start at square one, dead even with the writer. I’m an A-to-Z man; serve me the appetizer first and give me dessert if I eat my veggies.” (225)

He notes that Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca and Barbara Vine’s A Dark-Adapted Eye begin with considerable (perhaps too much?) backstory.

Too much backstory says to the reader, “We’ll get to the action soon, but first I need to force feed you a backstory.”

What else can you do? Here are some ideas:

- Allow yourself to have a prologue. Call it that (or a synonym for “prologue”). Have at it. A reader who doesn’t want backstory will simply skip it or return to it when puzzled.

- Label a chapter or section of a chapter accordingly: In the Beginning, for example, or Last Month, or Before I Knew Better. Or start a paragraph with these words to let your reader know what you are doing.

- Read a Nancy Drew, Hardy Boys, or Bobbsey Twins book to see how its various authors dribble in details about the past. For example, early in the first chapter in the eighth book about Nancy Drew, Nancy’s Mysterious Letter, “The three girls were returning from an overnight visit to Red Gate Farm, where at one time Nancy, with the help of her two friends, had kidnapped a counterfeiting gang. The solving of that mystery had been followed by Nancy’s tracking down The Clue in the Diary.” Backstory, pure and simple.

- Notice how current authors introduce backstory. For example, as I was reading Richard Russo’s third book of the North Bath Trilogy Somebody’s Fool, I noticed how adroitly the author slipped backstory into the action in the first chapter: “How had it all come to this?”

- Use a flashback to insert relevant backstory through action.

- Have a character react to a current event with reference to a past event.

- Use a character’s reflection (internal dialogue). Here’s an example from the second book of the Genevieve Planché series, The Fugitive Colours by Nancy Bilyeau. “I feel as if I lead two lives. One is that of a Huguenot painter, raised by her grandfather. . .now endeavouring to run a silk business. Then there is the other life, kept carefully hidden from everyone. . . .It’s a shadow life, one that was pushed firmly into the past when Thomas and I returned to England more than three years ago. And it must stay in the past.”

- Have the main character check a diary or appointment calendar to see what happened before (or during) the action of the narrative.

- Use dialogue during which one character explains something about the past to another character.

- Make backstory part of a letter from one character to another.

- Make backstory as natural as possible. Don’t have one character say to another in the middle of a sword fight, “Wait. Wait. I need to tell you what happened to make me so combative.”

Cautions About Backstory

DON’T:

- Tell everything. Decide to keep some parts of the backstory a mystery, to be solved by the end of your book.

- Include extraneous details in your backstory–even if you needed to know them yourself and found them fascinating,. Leave them out if the reader does not need them.

- Be tempted to tell a minor character’s backstory, even if it’s fascinating to you, unless you really need to do so.

DO:

- Be willing to give the reader enough backstory to have something to hang onto: tone, scene (place/time), a character (major or minor); be willing to give readers enough backstory so they read to get answers to questions generated by the backstory.

- Recognize when your backstory becomes so important it deserves its own book. Decide which book you are going to write.

In Medias Res

Stephen King, again: “You’ve probably heard the phrase in medias res, which means ‘into the midst of things.’ This technique is an ancient and honorable one, but I don’t like it. In medias res necessitates flashbacks which strike me as boring and sort of corny.” (224)

As King claimed, “I’m an A-to-Z man; serve me the appetizer first and give me dessert if I eat my veggies.” He doesn’t start meals in the middle, and he dislikes novels that start in the middle. However, he admits, “Even when you tell your story in [a] straightforward manner you’ll discover you can’t escape at least some back- story. In a very real sense, every life is in medias res.” (225)

I agree with his admission. I suspect he would have hated the first beginning (Example #1) I wrote for what became Through the Five Genie Gate. True, it starts at the beginning (“I was born. . . .) and I could have taken it through to dessert (as he put it) if I had wanted — perhaps even after-dinner drinks!

I rather think he might have liked Example #2 (being jilted) and Example #3 even better. Both are examples of in media res, a technique he used to begin some of his books:

Carrie

News item from the Westover (Me.) weekly Enterprise, August 19, 1966:

RAIN OF STONES REPORTED

It was reliably reported by several persons that a rain of stones fell from a clear blue sky on Carlin Street in the town of Chamberlain on August 17th.

Cujo

Once upon a time. . .not so long ago, a monster came to the small town of Castle Rock, Maine.

Pet Sematary

Louis Creed, who had lost his father at three and who had never known a grandfather, never expected to find a father as he entered his middle age, but that was exactly what happened. . .although he called this man a friend, as a grown man must do when he finds the man who should have been his father relatively late in life.

It

The terror, which would not end for another twenty-eight years — if it ever did end — began, so far as I know or can tell, with a boat made from a sheet of newspaper floating down a gutter swollen with rain.

The Dark Half

People’s lives — their real lives as opposed to their simple physical existence — begin at different times.

The Stand (later version)

“Sally.”

A mutter.

“Wake up now, Sally”

A louder mutter: leeme lone.

He shook her harder.

“Wake up. You got to wake up!”

Charlie.

Charlie’s voice. Calling her. For how long?

Sally swam up out of sleep.

Rose Madder

She sits in the corner, trying to draw air out of a room which seemed to have plenty just a few minutes ago and now seems to have none.

The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon

The world had teeth and it could bite you with them any time.

Black House (sequel to the Talisman)

Right here and now, as an old friend used to say, we are in the fluid present, where clear-sightedness never guarantees perfect vision.

From a Buick 8

Curt Wilcox’s boy came around the barracks a lot the year after his father died, I mean a lot, but nobody ever told him get out the way or asked him what in hail he was doing there again.

Where to Begin in Nonfiction

Few writers of nonfiction begin their articles, essays, chapters, books, or other forms of nonfiction at the beginning. They usually introduce their ideas through something that will connect the reader to what they want to say.

Think about the opening words in the following examples of nonfiction. In what ways are they backstory?

Examples

Example #1

“If you ever saw the old movie ‘Fiddler on the Roof,’ you know how warm and emotional Jewish families can be. They are always hugging singing, dancing, laughing, and crying together.”

(from David Brooks, columnist in The New York Times Opinion Section, Sunday, October 22, 2023)

Based on these few words, can you guess what this opinion column is about? Is it backstory to a review of “Fiddler on the Roof” or a commentary on Jewish families? Or is it something else entirely?

The title helps: “Give the Gift of Your Attention.” Now you know (or suspect) more. The first few lines might be an example of people who pay attention to others. And that’s what it is.

The last line of the column is “That was a guy who was truly seen.” In the middle of his column, Brooks talks about a book he wrote to address today’s widening gaps among people, groups, regions, and countries – How to Know a Person.

Example #2

As a preteen in the early 2000s, Katie Leigh Jackson painted her bedroom bright yellow and stenciled pink hibiscus flowers on all of the walls. “I essentially made my first wallpaper – without the paper.”

(Meredith Sell, “Wall Flowers,” in the October 2023 edition of the magazine 5280, a monthly that celebrates all things Colorado, many things in the Western United States, and often from around the world.)

This is an example of backstory in nonfiction. The first paragraph leads into the main story, which begins with, “Today, Jackson points to that childhood project as an early example of her enduring love for wall art.”

Consider this: Backstory may BE the story in nonfiction. Authors of articles sometimes write a backstory that explains another piece of nonfiction – their own or something written by another author.

Example #3

Kihekah Avenue cuts through the town of Pawhuska, Okla., roughly north to south, forming the only corridor you might call a “business district” in the town of 2,900. Standing in the middle is a small TV-and-appliance store called Hometown, which occupies a two-story brick building and hasn’t changed much in decades. Boards cover its second story window. . . .

(Noah Gallagher Shannon, “The World Builder,” in the October 8, 2023, edition of The New York Times Magazine.)

This paragraph and a few more sentences establish the background for the story of how Martin Scorsese chose a set location for his 28th feature film Killers of the Flower Moon, based on the book of the same name by David Grann. It is description that leads the reader into the “so-called 1920s Reign of Terror, when the Osage Nation’s discovery of oil made them some of the richest people in the world but also the target of a conspiracy among whites seeking to kill them for their shares of the mineral rights.”

Before getting into the article, the author establishes a setting that most readers can understand: a small town, an avenue, a business district and some stores, the condition of the buildings. Then, readers might be ready to learn about what happened in such a town in the 1920s.

Example #4

At twenty-six, in 2006, the year before the iPhone launched, I found myself driving a red Subaru Outback — the color was technically “claret metallic,” the friend who’d lent me the car had told me, in case I ever wanted to touch up the paint — on Highway 12 in Utah. I was heading to the East Bay after a painful breakup in New York. I remember, wrongly, that I was listening to a book on tape, a work by a prominent linguist, as I moved through the alien landscape, jagged formations of red rock towering against a cloudless sky.

This article could be about any number of subjects: the iPhone launch, Suburu cars, Utah highways, paint colors, East Bay, New York, break-ups, books on tape, linguistics, Utah’s landscape.

The scene lets the reader come to know something about the author before launching into what its real subject. The technique is an example of casting a wide net to draw people in, to make them want to read more. The design of the article is like an upside down triangle, broad at first and then narrowing gradually down to its point, a premise that at first seems unrelated to the first few lines. The sub-title explains it well, however, and the author uses the information in the first few lines to lead into his argument:

The Hofmann Wobble

Wikipedia and the Problem of Historical Memory

Ben Lerner, Harper’s Magazine, December 2023)

Beginning Nonfiction

If you do not consider all of what you’re writing as backstory to something else (something you or another author wrote that needs development), you ‘ll find that many of the strategies for fiction are suitable for use in nonfiction, too. You can pull your beginning from any of the content you include anywhere in your nonfiction piece.

For example, I began many of my nonfiction articles and books with a second-person (“you”) narrative. Here’s an example:

You are thinking about teaching outside the United States, and you’re wondering what kind of professional learning opportunities you will have. If you teach in Poland, you will likely have the assistance of a school-based pedagog who will help you and your colleagues with instructional strategies.

Lois Easton (June 2013). A Global Perspective: What professional learning looks like around the world, The Learning Professional (The Learning Forward Journal).

I intended the beginning to draw the reader into the data. The next paragraph begins If you teach in Albert, Canada, you have. . . . The third paragraph begins In Brazil, you might be involved in individual or collaborative. . . . Subsequent paragraphs describe what the reader might experience in professional learning in Australia, Korea, and Japan.

I hoped that by the time I got to the overview of the report and my own research, the reader would be interested in how teachers are helped to improve in other countries. I hoped they would compare (and, most likely, contrast) professional learning in their own U. S.-based schools and universities with what was available in other countries.

Here are a variety of ways to begin nonfiction:

- With a case study (real or aggregated from several real studies; fictional, but realistic and identified as such).

- With a question that is likely to entice your reader into your piece.

- With a comparison between what readers are likely to know and what they’ll discover in your piece. For example, “Today X is . Ten years ago it was . What has made the difference?” Or, “Today Y is . If we do nothing, in ten years Y will be . What can we do?”

- With a description of a relevant part of your own story or life situation.

- With a “What do you call” joke, such as “What has four wheels and flies?” As a reader, you may have thought “airplane” and then reconsidered your answer if you were uncertain about the number of wheels on a plane. In this example, the author wrote the right answer (“garbage truck”) and in this way lured you into a history of garbage trucks. Other standard joke forms may work well as a beginning for something you’re writing.

- With a compelling description of a person, place, or thing. . .which leads to an essay about that subject.

- With a description of “what if” situation, such as “What if you believed you were the first person to see a new variety of animal?” Let the reader imagine the animal, the setting, and possible actions. Then continue your nonfiction piece about ecologists, zoologists, archaeologists – and even everyday non-scientists – who found a new species.

- With a quote, poem, aphorism, proverb, or other pithy statement to engage your reader with your subject.

- With a photograph, drawing, schematic, or table to present a visual prologue for your reader to contemplate.

- With a metaphor (even a cliché), analogy, hyperbole, or obvious understatement to begin your work.

- With a dialogue between or among people who are similar/dissimilar, believe/doubt, support/disavow, like/dislike, etc., something about your subject.

- With a process related to your subject. Intrigue your readers in a variety of ways: missing a key step, adding an unnecessary step, or masking what you are doing. For example, write about how to make an omelet without using that word or the word egg. Your essay may be about key elements of making omelets, French cooking, egg dishes, or. . . .

If you already have a beginning, congratulations. Use it, and then examine it. Does it work? Where does it lead? Is it enticing?

Allow yourself to begin without a beginning. It’s a little scary, but risks nothing. Start with the first thing you want to say about your subject. As you write, note each possible beginning (I use a B? to draw attention to something that might make a good beginning).

Be sure to audition your beginning. Does it lead in the right direction? For example, what part of your writing must come after your beginning? If your beginning is about all the flat tires your great grandfather experienced in his 1913 Ford Model T Roadster in the middle of a dirt road in Kansas, continue writing about cars in 1913, particularly in the Midwest, or write about early Fords. If the sentence following your description of your great grandfather’s experience is about Corvettes in Malibu, your beginning has been squandered. The reader will feel misled.

(Of course, you could save your beginning if you compared driving the Roadster in 1913 in Kansas to driving a 202X Corvette on a paved highway in California.)

Where are you willing to go to begin your piece of writing? All the way to the end? To somewhere in the middle? At the beginning? Any of these directions