It’s time to make good on what Keston Harris declared in Your Story Is Nothing Without Its Characters (https://medium.com for Sep 23, 2020) which I included in Blog #11:

You can’t have a good plot without well-written and complex characters. Likewise, if your characters are written well, their interactions and conflict will weave the plot. The two build each other up. It’s a partnership, not a ‘take your pick.’

Blog #11 was called “Giving Chase to Plot.” Now, let’s hear it for character. I’ve divided my discussion of character into two blogs:

- Blog #12 Courting Characters

- Blog #13 Creating Characters

Blog #12 will help you think about types of conflict and the kinds of characters you’ll want in your novel or short story to develop and resolve your conflict(s): dynamic or static characters; rounded or flat characters; at least one protagonist, at least one antagonist, dual protagonists/antagonists; and perhaps a love interest or foil.

Blog #13 will help you think about different ways to develop characters: questionnaires, interviews, the Polaroid process, relationship maps, timelines, and backstories.

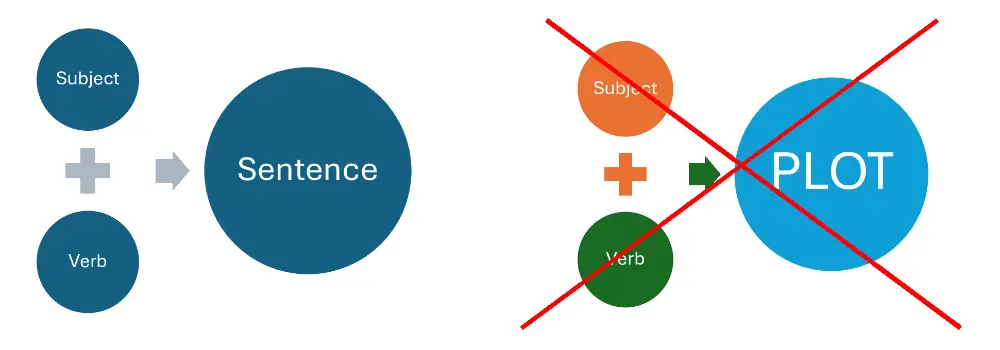

Plot: More Than a Sentence

At the end of the last blog (#11 Giving Chase to Plot), I presented this table and invited you to “Choose one [word] from Column A and one from Column B. Imagine a plot based on the two words. Imagine a few episodes you’d want to develop your plot.”

| Column A | Column B |

|---|---|

| He | decided |

| The jury | left |

| She | argued |

| They | cut |

| The students | pulled |

I wrote, “Each combination suggests a plot to me – at this point, not very exciting – but, still, a plot.” I lied. I found only one combination that suggested a viable plot to me: “The jury argued.”

I could do something with that, and perhaps with any other word from Column A paired with “argued.” Another pairing (maybe/possibly/ perhaps) could lead to a plot: Anything from Column A plus the word “left” is one, such as “The students left.” Not exciting, but perhaps you can imagine how you would make it exciting.

You could pair the word “cut” from Column B with any of the words from Column A, such as “they” for “They cut.” (But what did they cut?) This plot needs an object, perhaps “cake” as in “They cut the cake.”) Ho-hum.

But these: He decided? She left? They pulled? Not really plot-worthy.

Subjects and Verbs

If you have remembered any of the grammar you were supposed to learn in school, you have probably remembered subjects and verbs. Column A above consists of subjects. Column B consists of verbs.

Except for two subjects in Column A (“The jury” and “The students”) the choices in Column A are wholly unsatisfactory. The pronouns “He,” “She,” and “They” are impoverished when they don’t refer to anything; they have no noun reference, such as “The man with the cut lip. . . .” or “The white cat that could have been the feline in Hello Kitty with its blue bow and wild smile. . . .”

The verbs aren’t much better. So, although you need a subject and a verb to make a sentence, you need much more to make a plot.

What do you need? (P.S. The answer is not “noun reference.”) You need

CONFLICT:

Conflict

Conflict unites plot and character, giving you a story to write and giving your readers a story to listen to or read. Conflict enriches a simple subject and pins down the verb.

Let’s say the conflict is between a shopper who thinks she has been cheated and a grocery store clerk who is positive she has rung up a discount for the product in question. Conflict: Cheating. Subject: shopper. Verb: argued.

Good start.

Conflict comes from many sources. Writers may disagree on how many types of conflict exist, but most agree on at least four basic sources of conflict:

- With self

- With others

- With the environment

- With the supernatural

Here’s a more complete list from MasterClass at https://www.masterclass.com/articles.

- Person Versus Person

- Person Versus Self

- Person Versus Fate/God(s)

- Person Versus Nature

- Person Versus Society

- Person Versus the Unknown/Extraterrestrial

- Person Versus Technology/Machinery

You may want to think of “Person” as “Character”:

- Character vs society

- Character vs nature

- Character vs supernatural

- Character vs technology

- Character vs character

- Character vs fate

- Character vs self

No matter how you decide to name the type of conflict, be willing to use your imagination. Begin by choosing any character from the pictures below and applying any of the conflicts above to that character.

Stretch your imagination a bit. Choose for any pictured character what seems to be an unlikely type of conflict. For example, choose one of the children and imagine the conflict as Person Versus Fate. Repeat with other characters and other types of conflict.

Now push into the realm of creatures (as distinguished from Persons). Select any of the types of conflict and then select a creature.

Next, choose for any creature what seems to be an unlikely type of conflict. For example, choose the lime green creature in the bottom row, left, and imagine a conflict between this creature and fate.

Stereotyping

One of the risks of deciding on the type of conflict a character or creature faces is that you might stereotype that character or creature. Consider how people usually think of characters or creatures in the following roles:

Firefighter Member of the Clergy Accountant Athlete Bank Robber

You might have decided that (obviously) a firefighter is brave. Therefore, a firefighter might have a conflict with nature. A member of the clergy is (of course) empathetic but might also experience conflict with the supernatural, such as her belief in a god. An accountant is matter of fact but may have a conflict with society and its rules and laws. An athlete is expected to be strong but may experience doubts about herself. A bank robber is usually seen as a bad person, capable of violence, but this character’s conflict may be with fate.

If you easily think of a conflict along with one or more perfect characters to wrestle with it, beware. You may be at the risk of stereotyping a character or creature in terms of conflict. Remember: the brave firefighter, the empathetic member of the clergy, the matter-of-fact accountant, the strong athlete, the maleficent bank robber.

Readers and listeners who detect the use of stereotypes may become disenchanted with the story and its author. Don’t risk that. In fact, submit to The Opposite Test anything you decide about the conflict that propels a character/creature. For example, put the character/creature that would stereotypically be in conflict with technology into the opposite situation, perhaps in complete harmony with technology. . .or even becoming technology.

Stereotypes may tip over into the land of archetypes.

Archetypes

An archetype is a stereotype that is so familiar that mere mention of the archetype conjures a comprehensive picture of the character/creature. Here are some of the most common archetypes:

- Innocent

- Everyman

- Hero

- Outlaw

- Explorer

- Creator

- Ruler

- Magician

- Lover

- Caregiver

- Jester

- Sage

These 12 archetypes came from literature, mythology, and real life. They are comprehensive in terms of physical characteristics (we can “see” them); language (we can “hear” their monologues, both interior and external, and their dialogues with others); their demonstrated or perceived emotions (or self-talk about their emotions); their actions; and their inner thoughts. They are readily available to audiences. (See Blog #8 More Than AP: Audience, Purpose, and Attitude for more about the meaning of audience.)

You can probably think of characters/creatures in books, movies, television series, games, and other media that use the immediacy of archetypes to tell a story. Who would you nominate for the archetypal hero, explorer, creator, caregiver, jester, sage, or any of the other archetypes?

Although you can purposefully create characters or creatures that are stereotypical or archetypical (sometimes spelled and pronounced as archetypal), generally you want to avoid doing so. . . .unless you are Nathalie Haynes, an author who offered in her book Stone Blind a new way of looking at the archetypes of the Greek gods through today’s lenses.

On second thought, she actually countered those archetypes with her witty, nuanced,and ironic portrayals. l don’t believe I will ever think of Athene, Perseus, Poseidon, Zeus, Medusa, and other major and minor Greek gods as their archetypes.

Unless you are Haynes or choose to use stereotypes and archetypes to achieve some purpose, you probably want to focus on creating characters/creatures that are real to you and to the reader/listener.

Put the characters you create to a test of authenticity. If you nose-out an unintentional stereotype or archetype, contest it. Could you banish that character/creature from your story or replace the aspect that made it stereotypical or archetypal to its opposite – and still have the story work?

Types of Characters

Over centuries of storytelling, storytellers and their audiences have realized that characters have different functions. Here are three ways to contemplate characterization.

Dynamic and Static Characterizations

Not every character/creature needs to be developed to the same degree. Some are dynamic, learning, experiencing, and going through some kind of change. Usually the most important/main characters are dynamic, but sometimes they can be static as other characters go through changes they have sponsored. Here are some dynamic characters:

- Ebenezer Scrooge in A Christmas Carol

- Romeo and Juliet in Romeo and Juliet

- Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz

- Aladdin in Aladdin

- Harry Potter in novels and movies

You can probably name many other dynamic characters in films, television series, games, novels, short stories, etc.

Characters/creatures may be dynamic in either a positive or negative way. Which dynamic characters seem positive to you? Which seem negative?

Think, for a moment, what a story would be like if all characters/creatures were dynamic, all going through some kind of change. You would have to develop the before, during, and after stages of each of your character’s/creature’s changes. That’s probably workable if you have only two or three characters. But what if you have forty? With forty, you might get tedium, for both the author and the reader/listener.

So, some characters are less than dynamic. They may be fully static, not changing much if at all but contributing to the plot. They may be major characters/creatures, but they are essentially the same at the beginning of your story as they are at the end. Which characters in the clip art above could be called dynamic? Which could be called static? (Of course, I’ve just asked you to indulge in stereotyping – the moving characters may not be dynamic; those standing still may not be static!)

Static characters may also be negative or positive. Here are some examples:

- The stepmother in the Cinderella story

- Yoda from the Star Wars series

- Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird

- Jay Gatsby in The Great Gatsby

- The Joker in the Batman series

At the end of the story, these important characters are about the same as they were at the start of the story. Can you think of others?

Another way to look at characters’ roles in a story is to see some as rounded or fully developed, and some as flat or undeveloped. Dynamic characters are usually (but not always) round, and static characters are usually (but not always) flat. Don’t labor over the distinctions dynamic/round and static/flat. Just use the words that help you distinguish how you understand various characters in your story.

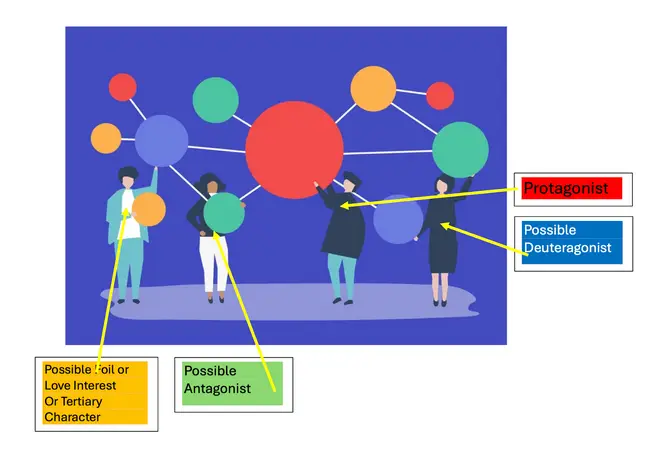

The ISTs

I call them The ISTs (because many of the types end in -ist). They describe what a character might do in a story. You’ve probably heard of at least the first two:

Protagonist: This is the main character in the story. Sometimes people think the word protagonist means FOR (pro) something, such as for freedom. That’s not always the case, just as the next type is not always AGAINST something. The protagonist might actually be an anti-hero, such as Walter White in Breaking Bad.

Let’s say the character to the left is the protagonist. Do you think she is an anti-hero (therefore, an ANTI-PRO-TAGONIST)?

The protagonist can be understood as a central force, advancing the story, building the meaning of a story, and dealing with the antagonist. The protagonist is probably dynamic and well-rounded. These are the characters most readers care most about. If there’s only one character in a story, that character is the protagonist.

Think of

Ellen Ripley in Alien

Harry Potter in the Harry Potter series

Luke Skywalker in the Star Wars series

Captain Kirk in the Star Trek series

James Bond in the James Bond movies

Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind

Alice in Through the Looking Glass and Alice in Wonderland

Antagonist: This is the character in the story that works against the protagonist. As in the word protagonist, this character is neither for nor against something, like AGAINST (anti) freedom.

Think of

Lex Luther in the Superman series

Lord Voldemort in the Harry Potter series

Captain Hook in Peter Pan

Scar in The Lion King

Agent Smith in The Matrix series

The Trojan Horse in The Iliad

The film Catch Me If You Can plays around with common understandings about protagonists and antagonists. At first, Frank Abgnale (played by Leonardo di Caprio) is the protagonist; then he becomes the anti-hero protagonist. Carl Hanratty (played by Tom Hanks) is the antagonist who tries to catch Frank. As the plot unfolds, these characters switch roles, with Carl becoming the hero protagonist and Frank the antagonist.

Deuteragonist: This simply means that the story has two (or more) characters that serve as the protagonist together; you can also write a story with dual antagonists. Sometimes, one character is more the protagonist/antagonist than the other, who can be seen as a sidekick, confidant, or best friend rather than as co-protagonist/antagonist. In the “confidant” scenario, the second character might not be affected in the same way the main protagonist is.

Think of

Harry Potter and Hermione Granger in the Harry Potter series

Sebastian and Mia in La La Land

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid in the film of that name

Thelma and Louise in the film of that name

Ann, Martin, Rose and Peter in the Chronicles of Narnia series

Be forewarned: A story with more than one protagonist can get complicated, as each persona changes over time, sometimes moving closer to each other, sometimes further apart. Their motivations for acting as co-protagonists may be different, perhaps even reaching a point of conflict. The same may be true for linked antagonists. Also, the more protagonists/antagonists you have working together, the more complicated your writing will be. Perhaps, as C.S. Lewis did, you’ll have to make one character the main protagonist and the other characters “sidekicks.”

Let’s leave the ISTs and look at three other roles characters might play:

Romantic/Love Interest: This character is desired by the protagonist who is defeated by the antagonist from winning this object of desire. Romantic interests will be rounded characters and either dynamic or static. The object of the protagonist’s interest may even become the antagonist. Here are some well-rounded romantic interests:

Daisy Buchanan in The Great Gatsby

Audrey in Little Shop of Horrors

Peter Wimsey in Strong Poison and later Lord Peter novels

Peeta in The Hunger Games series

Christine in Phantom of the Opera

Bella in The Twilight series

Lois Lane in the Superman movies and television shows

Foil: This is the character who functions to sharpen the protagonist’s qualities. Often, the foil is opposite the protagonist in many ways, and the protagonist reacts to the foil by changing or doing something different. The foil is not the antagonist but helps prepare the protagonist to take on the antagonist. Here are some examples:

Mr. Spock in the Star Trek series

Draco Malfoy in the Harry Potter series

Mercutio in Romeo and Juliet

Banquo in Macbeth

Tom in The Great Gatsby

Watson in Sherlock Holmes

Tertiary Characters: Finally, you’ll have other characters in a story. They don’t have specific functions in the plot, but they might have their own sub-plots that link to the main plot. They may be flat characters (rather than rounded) and static (rather than dynamic). Or rounded and dynamic. Or. . . . Sometimes, authors need to plan the backstories of some tertiary characters in order to understand the connections they may have with the protagonist, antagonist, etc.

Let’s put the ISTs and their co-workers together:

An Important Caution

It’s easy to overdo the prep work for characterization. Beware what’s called analysis paralysis. If you find you are stuck on whether

- a character should be the only protagonist in your story or buddy-up with another character;

- the protagonist and antagonist are beginning to sound more like each other than opposed to each other;

- a character is mostly static but occasionally dynamic;

- the conflict you’ve created may not create enough tension to keep the reader reading and the listener listening;

- your character is verging on a stereotype; or

- you need to employ an archetype as the basis for one of your main characters.

worrying and just start writing. Trust your process of character development so far – which may be not much more than reading this blog. If you read Blogs #1 (Paying Attention: A Writer Notices Everything) and #2 (Always on My Mind: Thinking Like A Writer), you’ll let what you learned in the first part of this blog roll around in your mind a bit. Start writing and trust the characters to develop as they must. . .and be willing to change them as they dictate.

You may not believe that such a so-called sloppy process will work. You may feel compelled to do more work on characterization before starting to write. Here’s what a few authors say about the fear that you haven’t done as much characterization work as you should:

Anne Lamott to her students: “Remember the Mel Brooke’s routine in The 2,000 Year-Old Man, where the psychiatrist tells his patient, ‘Listen to your broccoli, and your broccoli will tell you how to eat it.’ And when I first tell my students this, they look at me as if things have clearly begun to deteriorate.” (11) Listen to the broccoli.

Brenda Ueland: When you are writing you will probably think harder than you ever have in your life and more clearly. But self-consciousness, anxiety, ‘intellectualizing’ (i.e., primly frowning through your pince-nez and trying to do things according to prescribed rule as laid down by others) will be untied from you, will be cast off.” (58)

Rose Tremain (Dame, British novelist, short story writer, and former chancellor of the University of East Anglia): “Respect the way characters may change once they’ve got 50 pages of life in them. Revisit your plan at this stage and see whether certain things have to be altered to take account of these changes.”

That said, take what you can from Blog #12. You’ll have some labels, tags, or pigeon-holes to help you mull over characters you want in your story, novel, screenplay, drama, etc. Read Blog #13 for some down-to-earth, practical things to do vis-à-vis characterization.