Now that you have courted characters (Blog #12) for your story, novel, screenplay, or other fiction, you’re ready to create them. I know! That sounds backwards. But once you have in mind a character – you have courted one or more characters and invited them into your writing – you’re ready to develop or create them. You’re ready to make friends with them and set them on the road to your story.

You think you know who your protagonist and antagonist are, and perhaps you visualize a co-protagonist or -antagonist, a love interest, a foil, or even some tertiary characters.

You’ve determined that none of these characters will be stereotypes or archetypes unless characterizing them as such is purposeful. You will develop the three main characters so that they are rounded and dynamic.

I divided the topic of characterization into two blogs:

Blog #13 Creating Characters (this one)

Blog #12 described types of conflict and the kinds of characters you’ll want in your novel or short story to develop and resolve the conflict(s) that unite plot and character.

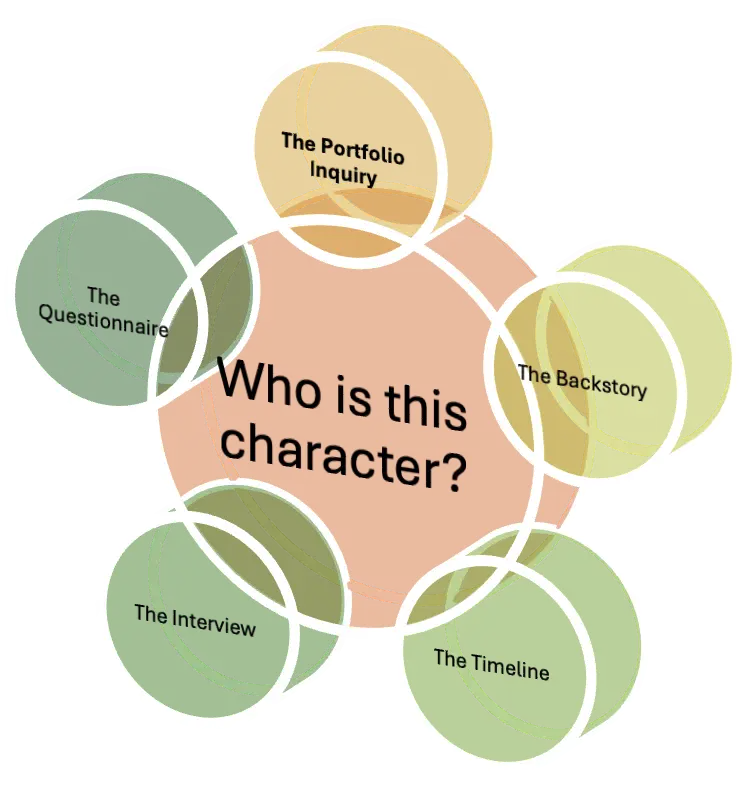

This blog, #13, helps you think about different ways to develop characters (from a questionnaire/interview to a relationship map, and finally to one or more backstories)

Processes for Creating Character

Here are a few strategies that will help you set your characters into motion.

Construct a Questionnaire or Interview Your Character/Characters

Questions you can use in questionnaire form or as the basis of an interview can be quite helpful as you prepare to write your story. The good news is that you don’t have to develop these questions from scratch (or a questionnaire for asking them). You’ll find many questions and questionnaire forms online (some free). You can customize questions (adding, ignoring, revising) and a questionnaire in terms of what’s important to you.

Some Online Character Questionnaires

- MASTERCCLASS: https://www.masterclass.com/articles/character-development-questions-to-ask-your-characters

- NOW NOVEL: https://www.nownovel.com/blog/character-developmentquestions/

- THEATREFOLK: https://www.theatrefolk.com/blog/20-character-profilequestions

- WIKIHOW: https://www.wikihow.com/Develop-a-Character-for-a-Story

- GOTHAM WRITERS: https://www.writingclasses.com/toolbox/character-questionnaire/gotham#:~:text=One%20of%20the%20best%20ways,your%20story%20easier%20to%20write

- REEDSY BLOG: https://blog.reedsy.com/character-questionnaire/

The Basics

- Name

- Birth (Place, Year, Family)

- Current Age

- Gender

Childhood and Youth

- Remembrances

- Education

- Recreation

- Funny Stories

- Fears

Current Life

- Employment

- Education

- Living Situation

- Lifestyle

Physical Characteristics

- Height

- Weight

- How You See Yourself

- How Others See You

- Common Facial Expressions

- and Gestures

- Posture

- How You Talk and Listen

Some Good Categories of Questions to be Asked on a Questionnaire or in an interview

Personality

- Introversion/Extroversion

- Conscience/Compassion

- Openness/Agreeability

- Enthusiasm/Apathy

- Patience

- Determination

- Flexibility/Rigidity

- Respect

- Humility

- Diligence/Perseverance

- Self-Control

- Quirks

- Faults

Relationships

- Your Parents, Siblings, Other Family

- Your Current Family

- Love Relationships

- Your Best Friend

- Other Friends and Never Friend

- Co-Workers

- Bosses

- People You Supervise

Head, Heart and Soul

- Thinking Habits

- Creativity

- Beliefs and Misbeliefs

- Making Decisions

- Organization/Systems

- Goals

- Courage

- Humility

- Values

- Ethics

- Beliefs

- Fears and Hopes

- Wants and Needs

- Trusting and Being Trustworthy

Interests

- Fun and Adventure

- Favorite Media

- Sports

- Athletics

- Hobbies

- Travel

- Favorites

You can use the list of categories to formulate the questions you think are most important for you, as author, to know about each major and a few minor characters. You can also use the list of categories to review questionnaires online. Disregard categories or questions you don’t need; add others you do need; revise as needed.

You may want to augment the questionnaire or interview with some open-ended questions, such as these:

- What are your Prouds and Sorries?

- What are your Best and Worst Experiences/Memories?

- What have been your Most Embarrassing Moment(s)?

- What Secrets have you shared?

- What Life- Changing Moments (Ah-Hah Moments) have you had?

- What are your Favorite Possessions?

- Who would you Most Like to Meet?

- Would you prefer X or Y? This type of question is called a “This or That Question.” Why?

You can respond to your questionnaire as the author. Your answers will reveal how you think about the character you will develop, at least at this point in the process.

You can also respond to your questionnaire as the character. This is hard, and I must remind myself to answer as the character, not as an author who wants to be sure the character lives the life I, the author, want. Thinking as a character is worthwhile, however. I’ve sometimes been surprised by how I respond to a question on a questionnaire or in an interview as a character, sometimes realizing, “I didn’t know that!” What steadies me in this process is answering each question with “I” such as “I never finished high school” rather than “Celine never finished high school.”

You can also interview the character. You’ll need someone willing to play along with you as interviewer (another writer, a relative, a friend, or someone who owes you). Give the interviewer the questions you have formed but, otherwise, leave the interview up to the interviewer.

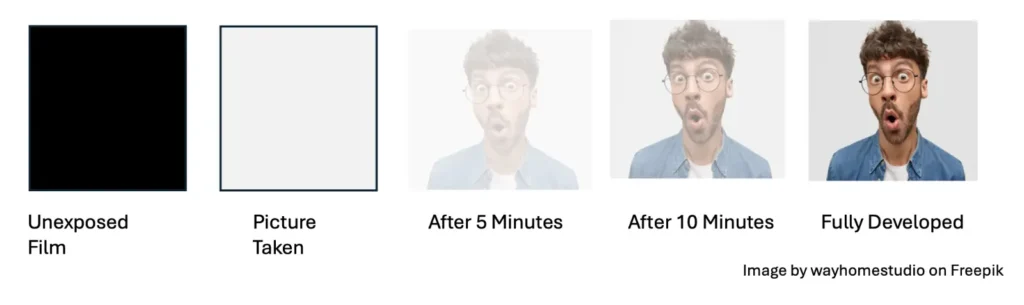

The Polaroid Process

You may not remember Polaroid cameras, sometimes called “instant cameras,” which used self-developing film to create a picture within minutes after the picture was taken. They harken back to American scientist Edward Land who developed the prototype in 1948. You can still buy Polaroid cameras and film and create “instant” pictures. The pictures weren’t exactly “instant,” however. They develop over time:

Put your characters through the Polaroid process.

When you are simply considering the types of character(s) you need and how they will function, you are dealing with “Unexposed film.” When you decide to create a particular character and click the shutter, that character might look like “Picture Taken.” However, complete an interview or questionnaire, and you may have a picture like “After 5 Minutes.”

As you write, you’ll find that your character will be about as clear as “After 10 Minutes.” Only when you get close to the end of your novel or story will you see your character “Fully Developed,” at least in Polaroid terms.

A website (https://www.gooroo.com/blog/polaroid-camera-tips-and-tricks) cautions that users of Polaroid cameras should keep the developing picture “somewhere warm and shield it from light until the photo has fully developed.” That’s probably good advice for character development, too. Also, the site advises, “Remember, as tempting as it is, don’t shake your Polaroids!” Also good advice for character development. Let your characters develop as naturally as possible, without much interference from you.

Relationship Maps

Once you have a good “Polaroid” feel (at least “After Five Minutes”) for the characters who will populate your story, consider constructing a relationship map. Position your characters to show their relationships to other characters. Put the protagonist in the center and position the other characters accordingly. You can find many examples of relationship maps online.

WHO'S WHO?

You can also map the characters in your story according to other connections, such as people working in the same company, graduating from the same college, or supporting a candidate for office. The most common of these other maps is the genealogy or family map.

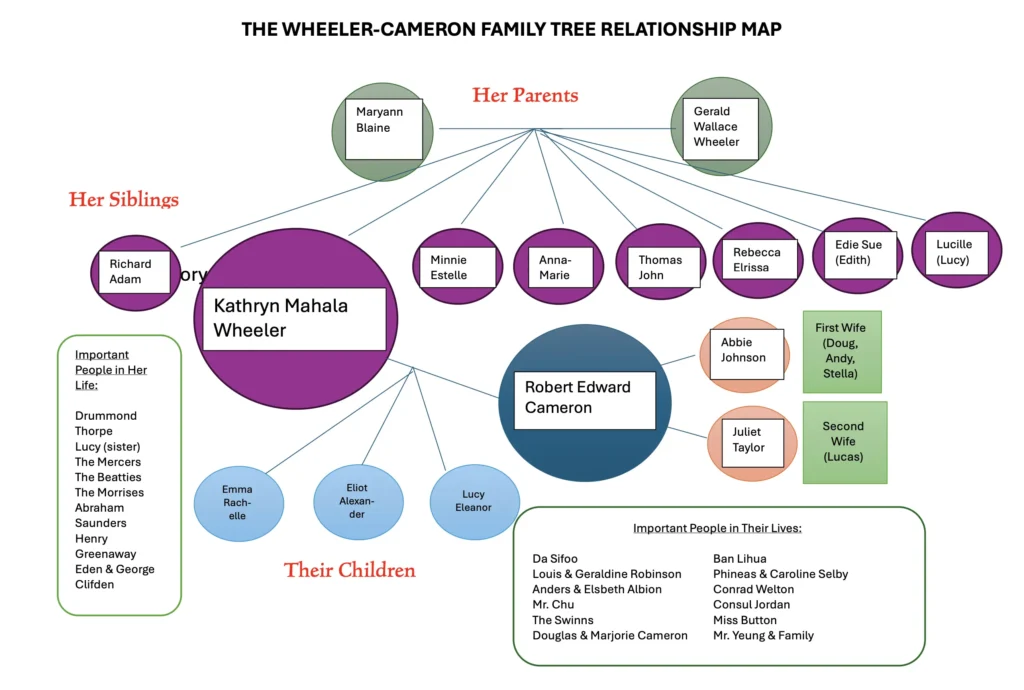

I became disenchanted with templates for family trees that I found online, few free, most fairly expensive. Also, the templates did not allow me to fit my main character’s family into the tree, at least not without a whole lot of work. So, I created my own trees, using Word and lots of text boxes and lines. Not beautiful, perhaps, but it got me organized and kept me that way.

Here’s one of those family trees, the one I did for the family of my main character in Through the Five Genii Gate.

Some Online Character Relationship Maps

Xmind: https://xmind.app/blog/how-to-produce-a-beautiful-character-relationship-map-with-xmind/

Milanote: https://milanote.com/templates/creative-writing/character-relationship-map

Storyfix: https://storyfix.com/improving-your-fiction-the-relationship-chart-part-1

Writing Stack Exchange: https://writing.stackexchange.com/questions/24296/character-relationshipmapping-software

Timelines

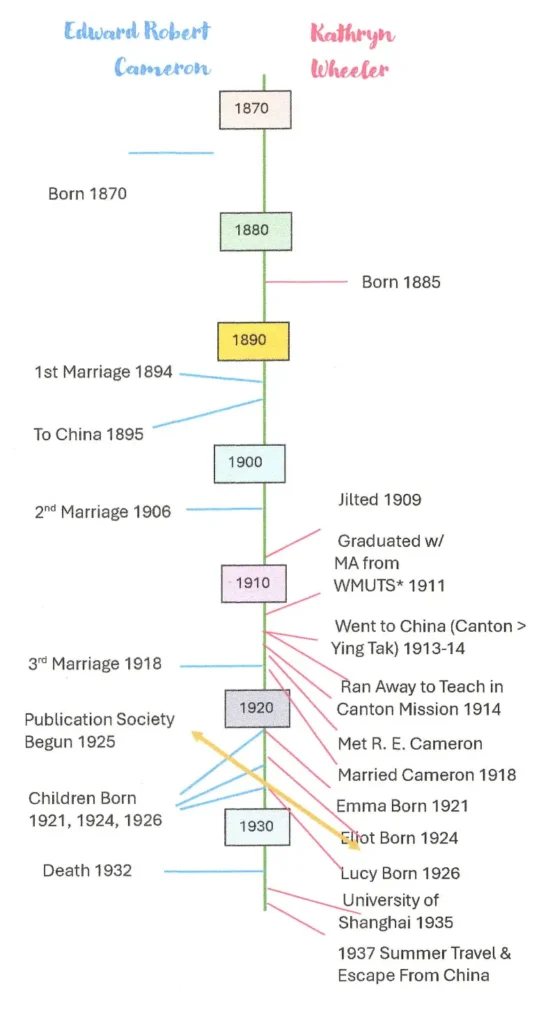

Another tool for understanding relationships is the timeline. Sure, you can (and probably should) do a timeline for your plot as a whole and also for your major characters – your protagonist and antagonist. The most important timeline I did was for the two major characters in my book, my protagonist Kathryn Wheeler Cameron and her husband Robert Edward Cameron, co-protagonist/confidant/deuterprotagonist.

This was a very basic timeline. I added other family members, particularly Kathryn’s children. I also added historical events such as the 1911 fall of the Qing Dynasty. My timeline got so big that I transferred it to a long piece of butcher paper and taped it across closet doors in the room I was using for writing (difficult to open the closet, however). At first it looked quite professional because I typed out dates and events and pasted them on the butcher paper, but then I just used a marker to add them to the timeline. More than once, that timeline saved me.

As you work on your own timeline, consider the following:

- Which characters – other than the protagonist and antagonist – would you want to include on your time?

- What other timelines interact with what your protagonist, antagonist, and others are doing in your story?

- What historical events (local, regional, country, worldwide, otherworldly) might have had an effect on your story?

- What aspects of the environment might have had an effect: where they lived, where they traveled? How did the environment differ locally; within a region or country; worldwide or otherworldly? How did it change over time?

- What aspects of the cultures your characters occupied might have had an effect? Like environment, is the culture different locally, within a region or country, worldwide, otherworldly? How did it change over time?

Backstories

The ultimate characterization tool is the backstory, which is the story of a character before your story begins. You can use the questionnaire/interview form, the Polaroid process, a relationship map, and/or a timeline to create a character’s backstory. Here are some important aspects of a backstory:

- Backstories do not actually appear in your novel or short story. They are not for the reader; they are for the writer. Don’t write, “Here is the backstory of my character, Elwood” and then insert the backstory you wrote to explore Elwood as a character. Don’t expect to slap your hands together and say, “That’ll do it. Whatever my readers need to understand Elwood is right here, all together.” Sorry. It doesn’t work that way.

- Readers are likely to skip a solid block of words that describes a character, even the main one. If they read that block of words all together, they may remember very little about it because they don’t have anything to hang the information on (such as a pivotal action). Note: Many readers also feel that way about long blocks of description and skip over them to get to the action.

- That said, you can use parts of your backstory here and there when they naturally help a reader understand what a character is doing and why. Backstory details should be dribbled out when needed.

- Think of revealing some aspect of a character’s backstory when it will help a reader gain understanding rather than telling the character’s entire backstory.

- Keep in mind that showing through action is better than telling the reader about your characters. Think of a likely action for your character, something that can be rounded a bit by a detail from the character’s backstory. Rather than telling that detail, show it during the action.

- Less is more. Backstory details should not overwhelm the reader or distract the reader from the plot. If a backstory becomes compelling, you may want to consider using it to write another book.

- Create backstories for characters who affect the protagonist(s) or antagonist(s), and second-tier characters, such as the love interest; the sidekick, confidant, or best friend; and the foil.

- Don’t create backstories for tertiary characters, especially if they are static (don’t change) and flat. Rather than write backstories about these characters, summarize the key characteristics of each in a single sentence, such as Evangeline was a “musician who was discovered on the streets and became an overnight sensation.” Get more examples of single-sentence characterizations at this site: https://robinpiree.com/blog/character-backstory-ideas.

- Check your backstory against reality, your own or others’. If a character’s backstory gnaws at you, it might just be too unlikely for your readers.

- Leave room at the bottom of your backstory to write about how the character might change. In fact, go one better, and prompt your thinking about the changes that a character might experience by asking this simple question: “How do I expect X to change during my story?”

- Descend into the rabbit-hole of ambiguity: What if X doesn’t change as I expect? What if he changes in Y way? What if she changes in Z way?

- Backstories may become highly important if a character is involved in a plot twist for which some explanation is needed.

- Some plot aspects, such as a flashback, might rely on a backstory.

- Experiment with backstory. Write it in a “Dear Diary” format. Write it as a series of snapshots, based on the character’s timeline.

Here are several ways to begin a backstory:

- With a one sentence summary (see #8 above).

Here are some others from the same site (https://robinpiree.com/blog/character-backstory-ideas):- A former athlete suffers a career-ending injury and has to find a new passion.

- A firefighter battles PTSD after a traumatic experience on the job.

- An orphan who grew up in foster care ended up becoming a detective to try to solve the mystery of her parent’s disappearance.

- A writer who grew up in a strict religious community eventually left and became a bestselling author by writing about her experiences.

- An immigrant came to a new country with nothing and worked her way up from cleaning houses to becoming a successful entrepreneur.

- With the most interesting of the questionnaire/interview categories, perhaps one that yielded surprising answers when you (as the character) responded to the questionnaire or interview. Here are some that I might use:

- Wants and Needs

- Fears and Hope

- Beliefs and Misbeliefs

- Creativity

- Friends and Never-friends

- Lifestyle

You’ll know which categories, questions – and the answers your character would have given to them – would be a good start to your backstory. Ideally, the beginning of your backstory will lead to description of other aspects of your character.

- With how your character responded to the more open-ended questions, such as

- Prouds and Sorries

- Life Changing Moments

- Secrets

- Favorite Possession

Examples of Backstories

Here are two examples of backstories. The first is from “Medium” an online journal from The Writing Cooperative. Samuel Olaniyan wrote How to Write Backstories: Uncovering Your Characters’ Past for the February 25, 2023, issue of the journal. After some quite useful discussion of what a backstory is, he provided a case-study backstory for P. T. Barnum in the movie The Greatest Showman. Olaniyan’s backstory focuses on Barnum’s misbelief. (https://writingcooperative.com/how-to-write-backstories-adce4dc1cacf)

Backstory #1 P. T. Barnum

“The story shows how the protagonist was dissatisfied with his life, given the job he was doing. He always wanted to be successful and do something exciting with his life, but his current lifestyle was nothing short of distasteful. The inciting incident that pushes the protagonist into action happens when he, along with everyone else, is laid off from work.”

What was the protagonist’s misbelief?

“Barnum was a child that had a million dreams, and as a grown man, he desired to give his family the life he dreamed of. His misbelief is born out of his fear, which is what makes the inciting incident truly matter to him.

“For Barnum, his misbelief was that in order to become successful, he needed to be wealthy, popular, and gain the admiration of everyone. While there is nothing wrong with being wealthy and popular, for Barnum, it was a belief born out of fear which would later become his undoing and help him realize his mistakes.”

What is that event that happened in their past that made them believe such a thing?

“Barnum was traumatized as a child. His future father-in-law at the time treated him badly and made him think that he would never be anything more than what he already was, which was poor, unsuccessful, and never good enough.

“This is the one event that haunted Barnum all his life and shaped him into the person he grew up to become. It was pretty evident how much anger and resentment he held for his father-in-law later on when he became wealthy.”

How are they dissatisfied with their life because they strongly believe that lie (their misbelief)?

“It was this childhood event that created the fear of failure, and poverty, which in turn created the misbelief that he could only be successful if he was wealthy and popular.

“This makes his dissatisfaction at the beginning of the story very evident. After he lost his job, he lost his comfort zone and was then forced to chase after his greatest desire with everything he had. Because if he didn’t, then his biggest fear would catch up with him and consume his family as well.”

What does my character believe would bring them true happiness or satisfaction based on their misbelief?

“Barnum believed that if he could become wealthy and popular and give his family the life he dreamed of, he would be truly happy and satisfied. Hence, losing his job presented him with the opportunity to find something new and begin his journey in pursuit of happiness.

“He is so fixated on giving his family a lifestyle of wealth in order to make them happy; however, this makes him grow more and more detached from his family, and he ends up making them unhappy. And he doesn’t realize this because he is controlled by his misbelief, which is the root cause of his dissatisfaction.

“He later realizes during his “AHA moment” that he cannot find true happiness in riches, fame, or success and decides that his family is all that matters, so he decides to invest more of his time in his family.”

Backstory #2 Kathryn Mahala Wheeler Cameron

Here’s the question I asked: “Would you rather work for someone or be the boss?” I started each of their backstories (5) with their answers.

My main character is so adamant about being in charge of her life that she abandoned her home in west Texas, endured wholly inappropriate preparation for what she wanted to do, and traveled alone in 1913 from the United States to China, prepared to be there all her life.

This attitude was not evident in her childhood. One of eight children of an impoverished rancher, she did her best to fit in and be helpful to her hard-working parents and the other children. But, for some reason, she wanted a way out of this existence.

Maybe she was always interested in escaping, but not aware of her desires until she met the man who would become her fiancé, a man who lured her with the possibility of escaping west Texas for China (!), to do something better than other possibilities, become a worthy missionary, and do something worthwhile. She was crushed when he jilted her as being unworthy of accompanying him to China as a missionary’s wife.

She looked around at the other possibilities and vowed she would not marry an impoverished rancher and raise a passel of brats. She wouldn’t work for a man in any subservient role (as housekeeper; store or hotel clerk; secretary, stenographer, or bookkeeper in an office). She wouldn’t consider teaching where, as she had already discovered, she was ruled by a male superintendent and a male-only school board that dismissed her without looking into the truth of a misunderstood situation with a beau.

She was practical, however. She acknowledged that she would always have bosses, mostly male, but she wanted to make the overall decisions about her life.

As she considered her possible futures, she fashioned a riposte to the fiancé who had jilted her: “I will do this all by myself. I will go to China as a missionary myself, not as the lowly spouse of a missionary.” She’s a nice lady, so I doubt she would have screeched “na-na na-na na-na” at him, perhaps putting her thumbs into her ears and wiggling her fingers back and forth, perhaps even sticking out her tongue at the fiancé who shunned her.

She was not overly religious for the time, so she probably would not have decided to become a missionary if her so-called fiancé had not offered her that as a way to escape from Texas, from a country whose protocols for women were Victorian, for another country that – well, she wasn’t sure just how China would be different.

She attended a conservative church with her family, even went to revivals where she claimed her faith repeatedly, only to be lured back into “sin” by one of the many boyfriends hovering around her. She was as pious as she was supposed to be until the next boyfriend came around. She probably believed in God but wasn’t revved up by the thought of proselytizing to and converting others.

She might have waited (doing what?) until a suitable beau came around, someone else who could get her out of Texas and help her find work worth doing, but she was anxious. She was already 22 when she met the fiancé who rejected her, almost old enough to be a spinster. She didn’t think of herself as beautiful or even pretty, and she wasn’t – at least in the sense of being blonde, buxomy, blue-eyed, and dimpled. But she was attractive: She was a little taller than most women, five feet, seven inches, and slender in those days. Her face was oval, almost square, and her skin light olive. Her hair was unexceptionally brown, straight, and long, often pulled into a twist at her neck. Her big eyes were hazel and said to be “soulful,” with eyebrows curved like commas above them. The rest of her features were symmetrical, an ordinary nose and chin, but her mouth curved into the shape of a rosebud (as it was called in those days).

She might have waited (doing what?) until a suitable beau came around, someone else who could get her out of Texas and help her find work worth doing, but she was anxious. She was already 22 when she met the fiancé who rejected her, almost old enough to be a spinster. She didn’t think of herself as beautiful or even pretty, and she wasn’t – at least in the sense of being blonde, buxomy, blue-eyed, and dimpled. But she was attractive: She was a little taller than most women, five feet, seven inches, and slender in those days. Her face was oval, almost square, and her skin light olive. Her hair was unexceptionally brown, straight, and long, often pulled into a twist at her neck. Her big eyes were hazel and said to be “soulful,” with eyebrows curved like commas above them. The rest of her features were symmetrical, an ordinary nose and chin, but her mouth curved into the shape of a rosebud (as it was called in those days).

Was she pretty enough to attract another beau? She didn’t think so and worried that her chances of doing so would diminish as she aged.

So she became the boss of herself, found a college that prepared women to be missionaries in their own right (and not just wives of missionaries), graduated with a master’s degree and honors, and rejected the Foreign Mission Board’s assertion that she could not go to China. Eventually allowed to go to China as a missionary, she still preferred to be the boss there.

She was appalled when she was required to do secretarial work at her first placement in Ying Tak, China, and tried to find ways to do what she wanted to do, even questioning the “mission of the mission” until her boss reined her in. Within a year she ran away from that situation. She was pleased with her second placement when she was allowed to pursue what she wanted to do – which meant abandoning her preparation for proselytizing. She enjoyed several years of teaching young girls who otherwise wouldn’t be educated in any formal way. When the man who was to be her husband rushed her towards their wedding, she ran away to the United States until she could make up her mind. When he died, she pushed the Foreign Mission Board to reinstate her as a missionary (not a missionary’s widow) and to publish the book she was writing about her husband’s contributions. She never gave up on those demands, choosing instead to find workarounds that got her what she wanted.

Revealing Characters

I suggested in the previous section of this blog that writers should think of revealing some aspect of a character’s backstory when it will help a reader gain understanding rather than telling the character’s entire backstory. Sometimes, directly telling the reader something about a character is effective. More often, however, a writer can accomplish more with readers by indirectly telling them about a character.

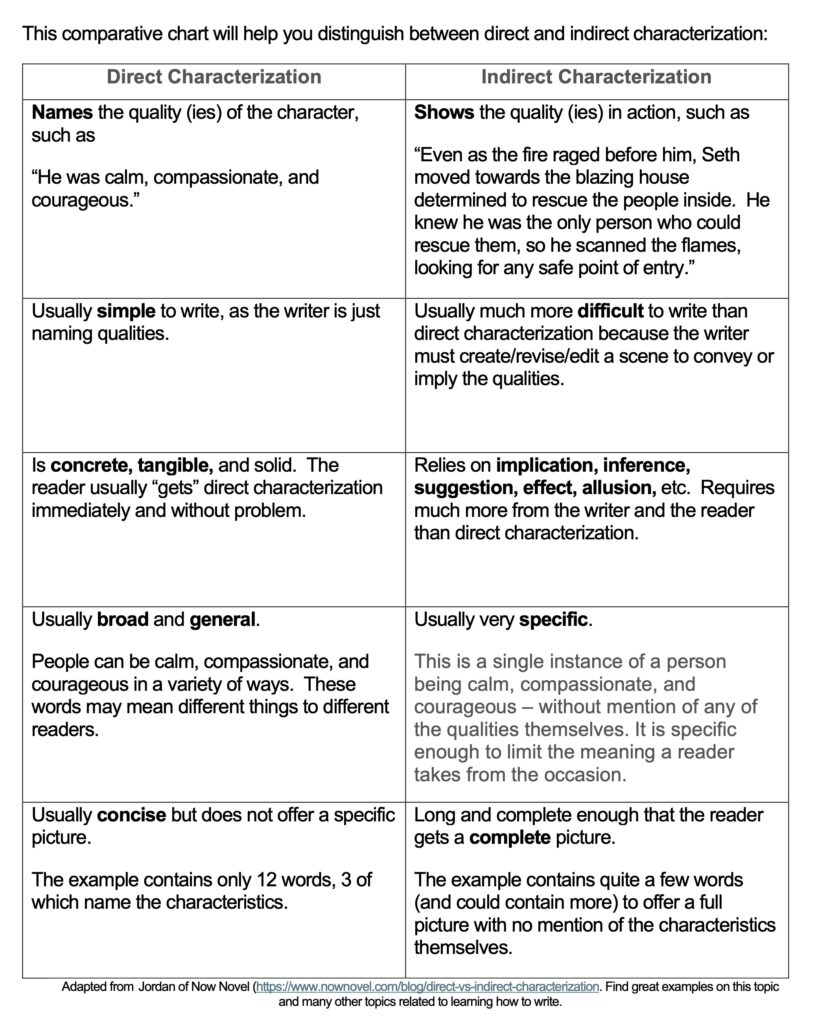

Direct and Indirect Approaches

An author is using a direct approach to characterization in the following descriptions:

- Axel is a student.

- Orson was born in the Midwest.

- Birdella loves tacos.

- Dara is a good dancer.

An author is using a simple but indirect approach to characterization by

- Having Axel take the only unoccupied seat in a classroom at Goodenough College and get out his books, notebook and pen from his backpack.

- Having Orson leave the newborn unit in Blank Children’s Hospital in Des Moines, Iowa, in the arms of his parents.

- Having Birdella take three tacos from the plate passed around the table and then ask for the remaining two.

- Having Dara whisper to Cosmo who is standing forlornly on the dance floor that she will teach him to dance the tango.

There’s nothing inherently wrong about direct characterization. In fact, direct characterization is a tool authors can use when they need or want to be concise.

Not everything needs to be shown in writing. I know that is nearly heresy in the writing world, but some things just need to be mentioned. Just naming something, such as the fact that Dara is a good dancer, allows the writer to show what happens when all the other boys in the studio begin to cut in so they can improve their tango talent.

Direct characterization is a little like an emoji that alerts the viewer to the gist of what is to come. Think of these:

An Indirect Approach to Characterization

Writers use a variety of strategies to indirectly achieve characterization:

- Action and/or Reaction

- Physical Attributes

- Attitudes (Posture, Facial Expression, Gestures, etc.)

- Environment (Setting) and Surroundings (Objects and Possessions)

- Dialogue Between Main and Other Characters

- Dialogue Among Other Characters

- Narrator’s Speech

- Inner Thoughts and Speech

The first four strategies are discussed in this blog.

The remaining four are discussed in Blog #14 “You Don’t Say?!”

Action and/or Reaction

Action that shows characters involved in scenes or incidents is favored by writers because it not only provides information about a character but also moves the plot forward.

Action, of course, can range from Dara’s dance step to the gunfight at the OK Corral at Tombstone, Arizona Territory in 1881. A step takes less than a minute; the gunfight (believe it or not) was over in a minute, yet each was replete with opportunities for revealing character.

Think of the individual actions a character might execute to take a small dance step, each of which could reveal something about the character. Think about the actions required by the gunfight and how any of them could reveal something about one (or more) of the characters.

How does a writer choose? One way to hone your skills in determining which details you’ll use in your writing is to watch the tactics actors use. As a wannabe actor, I learned that I needed to develop my own “business” to make my role realistic. The strategies actors employ sometimes are called “methods” and were developed and taught by famous theater practitioners, such as Konstantin Stanislavski, Anton Chekhov or Lee Strasberg.

You don’t have to study method acting, however. Just watch television (movies, a drama, a comedy, a soap opera, and even advertising) WITH THE SOUND OFF. As you watch, pay attention to what the actors are doing and try to discern what they are revealing about their characters and the plot through their actions. Pay special attention to the main characters (protagonist, antagonist, co-protagonist or -antagonist) and secondary characters (love interest or foil).

While you are watching with the sound off, watch how characters react to each other. Seldom will you see an action that is not met with at least one reaction, unless the action is so shocking that everyone is paralyzed, at least for a moment. Television is especially helpful in terms of recording action and reactions because one or more of the cameras usually moves from the action to at least one reaction.

You can learn especially potent character-revealing actions from the main characters but also from the secondary and tertiary characters.

Physical Attributes

You may want to take a direct approach to physical description, such as I did with my character Kathryn in Through the Five Genii Gate: “She had an oval, somewhat olive-colored fact and symmetrical features; bit (some would say ‘soulful’) hazel eyes under the straight lines of her eyebrows. . . .”

You may want to take a direct approach to physical description, such as I did with my character Kathryn in Through the Five Genii Gate: “She had an oval, somewhat olive-colored fact and symmetrical features; bit (some would say ‘soulful’) hazel eyes under the straight lines of her eyebrows. . . .”

I used an indirect approach to describing her when she had to ndure an interview with some very important (and, ultimately, mean people). I wanted this scene to be memorable to readers. “The popular hobble skirt made Kathryn mince her steps even though she wanted to take the stairs two-at-a-time to face the men who would decide whether or not she would go to China.”

She wanted to impress these men, so she held her head high, seated herself daintily at the edge of a velveteen chair, squared her clutch on the table in front of her, and then slowly peeled off her lace gloves finger-by-finger, and filed them next to her purse.”

This is a postcard (c. 1911) depicting a man pointing at a woman wearing a hobble skirt. The caption says, “The Hobble Skirt. ‘What’s that? It’s the speed-limit skirt!'”, because a hobble skirt limits the wearer’s stride. In the public domain. P.S. Usually the “hobble” was more decorative than a band tied just below the knees.

Use the list of categories for questions earlier in this blog to get a good idea about what you want to describe directly or indirectly to get your reader’s interest in one of your characters.

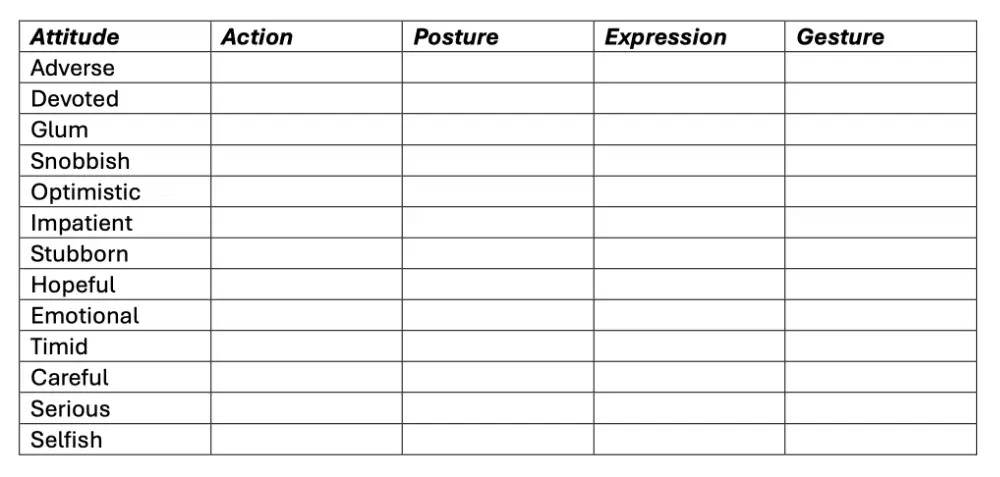

Attitudes (Posture, Facial Expression, Gestures)

Use the television method (sound off) to “read” the attitude of characters, such as the character below:

An attitude describes a state-of-mind but – because we can’t easily see what’s going on inside a mind or interpret what we see – we must rely on exterior signs: posture, facial expressions, gestures. Using just the exterior cues, what would you say is this character’s state-of-mind or attitude?

An attitude describes a state-of-mind but – because we can’t easily see what’s going on inside a mind or interpret what we see – we must rely on exterior signs: posture, facial expressions, gestures. Using just the exterior cues, what would you say is this character’s state-of-mind or attitude?

Choose several of the attitudes listed in the left-hand column below. For each attitude describe what a character might do (action) to indicate that attitude. Also describe aspects of posture, expression, and gesture that would suggest that attitude.

Image by rawpixel.com on Freepik

Environment (Setting) and Surroundings (Objects and Possessions)

Environment isn’t something you just add to a story: “Let’s see. How about if I put this plot and these characters onto a farm?”

A farm is a fine setting if it has a purpose in the story. Sometimes, the environment or setting of a story moves the plot. Sometimes, it’s like a main character, often the antagonist. Here are a few books and other media where setting is of great consequence. I am sure you can think of others.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

The Wizard of Oz by Frank L. Baum

Moby Dick by Herman Melville

The Harry Potter series by J. K. Rowling

The Lord of the Ring series by J. R. Tolkien

Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens

The Color Purple by Alice Walker

The Chronicles of Narnia by C. S. Lewis

Anything by Stephen King

Alien movie series

The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

Star Wars movie series

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Road by Cormac McCarthy

The Dune series by Frank Herbert

Oh, so many more!

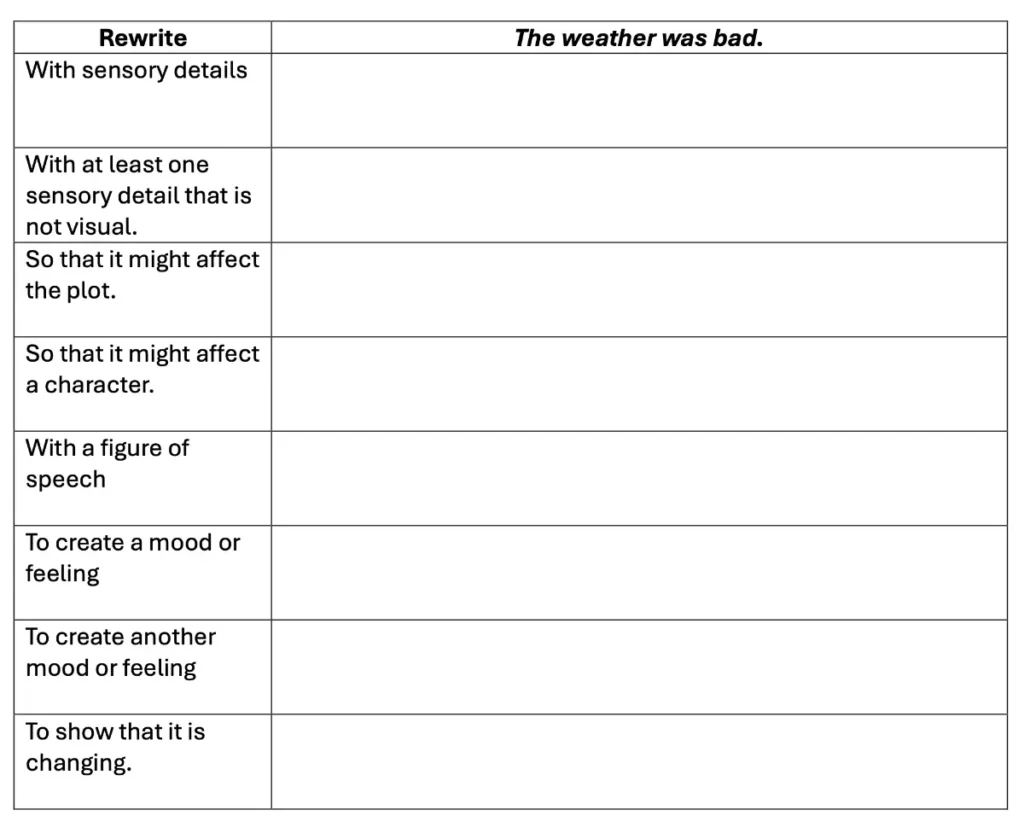

Here are some basics about setting or environment:

- Setting/environment is the time and place of your story.

- It may be about the climate or weather.

- It can be directly told, as in “The weather in Kelliher County was bad.” Ho-hum. What exactly does that mean? I’ll bet it means something different to each of us, to the writer of that sentence, and the people in Kelliher county.

- Setting/environment is much better if told indirectly, through sensory details: “The weather in Kelliher brought thick wet flakes that became frozen frosting on all the bushes, fence posts, and barely budding spring flowers.”

- The easiest details are visual, so stretch yourself to convey the scents, sounds, textures, and tastes of the setting you’re creating.

- As you work to show, not tell, create some figures of speech, such as similes, personification, personification, analogies. Compare unlike things. I tried to do that by comparing snow to frozen frosting.

- The setting or the environment doesn’t just sit there in the story. It moves the plot forward, it affects the characters, and it has a psychological effect on the reader. It creates a mood or feeling. The setting may feel ominous, comforting, confusing, relaxing, mysterious, dangerous, powerful, exciting. It may be changing.

Transform the direct statement about setting or environment

in the right-hand column

according to as many of the rewrite ideas

in the left-hand column as possible

Setting as Character:

In my book Through the Five Genii Gate, setting often acts like a character, influencing and affecting the human characters. Here is an excerpt from a train trip that gets the main character Kathryn and her two daughters, Emma and Lucy, from the Yangtze to Canton to escape the invasion of the Japanese prior to WW II:

After they reached Hankow, Kathryn secured third-class train tickets for a train bound for Canton (the only major city still open) – and was glad to have gotten them, judging by the crowd of desperate people outside the train station. For eight days, they sat on hard wooden benches during the slow, agonizing trip. At night they tried to sleep on one of two shelves that pulled down above their bench or on the bench itself using the sleeping bags they had brought for climbing Mt. Emei and creating pillows from their clothing.

The Japanese had been bombing the Hankow-Canton rail line, so the train was blacked out at night and consequently airless, claustrophobic, and suffocatingly hot. When bombing runs were expected, their train stopped entirely – shutting down the coal-fired engines so the train could seem to disappear. At the best of times lying on a wooden shelf would challenge sleep, but the thought of a bomb destroying the train – and them – made sleep elusive until sheer exhaustion took over.

Kathryn found it hard to corral her thoughts the first night. Whatever she happened to be thinking slid into an eternal question for her: “Why in the world did I come to China?” She even imagined that her husband Dr. Robert Edward Cameron, whom she called Ed, was still alive. What might they be doing as a family, she wondered, in – say – Paducah, Kentucky? Certainly not trying to find some measure of comfort on a hard piece of wood and listening to the skies at night for the telltale drone of a convoy of bombers, hoping to continue to hear it until the sound had faded and along with it the planes, into the distance. . .which would mean they had been spared once again.

She turned to her left side to bring some feeling back to her right arm, which had gone numb against the sleeping board and struggled to bring her thoughts back from the buzz of bombers. She murmured to herself, “So, why did I come to China?”

“Mother, what did you say?” Emma called out from the board below.

“Shhhh, dear,” Kathryn said, “It’s OK. I’m just talking in my sleep.” She heard her daughter turn over, caught a snore from Lucy on the bottom board, and then heard screams from somewhere in the crowded train. She recognized the sounds of birthing and then an undercurrent of soothing voices as others responded, perhaps pleading with the woman giving birth not to alarm others by screaming, as if she could easily stop the pain and forego the piercing shrieks. A man’s voice broadcast what sounded to Kathryn like a military command. Suddenly, all was silent. Then, Kathryn heard muffled cries as the laboring woman could not hold the pain without some noise. She pulled the blanket she had brought for Mt. Emei around her head and returned to her dream about coming to China. When she woke again it was to the faint sounds of a newborn mewling for its mother’s milk.

The setting of the train embodies the threat that Kathryn feels and her fear that they will all die before reaching safety, just as if a gunman had stepped on the train and brandished a pistol at its passengers. The setting is equivalent to a character.

More attention is paid to the setting or environment than to the surroundings (objects and possessions) in most fiction. This is because objects and possessions seldom “live to tell the tale.” They are momentary. Also, they may change as the main character changes. Or the character outgrows them.

Here are a few that are iconic:

- Indiana Jones and his whip or hat

- Aladdin and his lamp

- Calvin and Hobbes

- Linus and his blanket

- The whale in Moby Dick by Herman Melville

- Harry Potter and his owl (maybe)

- The picture in The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

- The mirror in Snow White

- The conch shell in Lord of the Flies by William Golding

- The One Ring in the J.R. R.Tolkien series

- Popeye and spinach (or a pipe in his mouth)

- The giving tree in Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree

- The rabbit in The Velveteen Rabbit by Margery Williams

Notice that children’s books and comic books often have an object that is as important as a character and essential to the plot.

Here are some suggestions about creating objects/possessions that move the plot and help the reader understand a character:

- Choose an object that is customarily with a character, so much so that the reader is concerned when the character is not accompanied by the object.

- Choose an object that is more than cute or charming; choose one that represents something important about a character, especially that character’s inner world.

- Describe the object as fully as possible, striving for more than details about how the object appears. How does it feel, for example?

- Strive for indirect description of the object by revealing it in action or reaction, within its environment, displaying feeling or mood, or – itself – identifying with another object or possession.

- Prepare a backstory, just in case you need it. How did the character get the object? How does the character feel about the object (and, if likely) how does the object feel about the character? How is the character’s history alike or different from the object’s history?

- What purpose (or purposes) has the object played in the character’s life? What does the object symbolize? How is it related to a theme or emotion? How is it related to a conflict, struggle, or relationship among the characters?

- What can the reader learn from the object about the character’s personalities, ideas, values, or incentives?

- How has the object changed, generally, and in relationship to the character?

- Weave the object and its uses into the story whenever appropriate. Don’t dump lots of information about the object and then drop it from the action. Think of the layers of a character’s personality and which can be revealed through the objects.

What Readers Notice and Remember

So much to do. So much to notice. So much to create. So much to choose!

Nobody said writing is easy. . .and writing characters has been described rightly as daunting, arduous, and onerous. Review the ways of getting to know your characters and then creating them, below

Then discover what readers say they notice and remember about the characters they encounter in stories.

Review of Strategies for Getting to Know a Character

Review of Ways for Revealing a Character

When you begin to write you can reveal a character indirectly or indirectly. . .or you can do both, first direction with a simple statement and then indirectly with details and action. An indirect approach is more fun for both the writer and the reader.

Four of the eight indirect ways to reveal a character are the colored hexagons in the chart: Physical Attributes, Action and Reaction, Attitudes, and Environment. The four gray hexagons are in Blog #14 “You Don’t Say!?” and relate to various types of dialogue.

As I wrote earlier: So much to do. So much to notice. So much to create. Writing characters is one of the hardest tasks a writer can do.

However, here’s what readers say they notice and remember about characters.

Here’s what keeps them reading.

Here’s how authors use elements of characterization to keep readers reading:

- Through the names they carefully choose for characters so that they are meaningful and memorable. This tip may lure you into stereotyping/prototyping. For example, you may name a brave male character Valiant and a cautious one Trevor. You may name an outgoing female character Sassie and a reclusive one Thea. Sorry if I’ve stepped on any toes here. You may create your own name for a character, such as Katniss, or characters, such as Muggles. Be sure the names you use are easily pronounced.

- Their physical descriptions (review the section about physical attributes above).

- Their quirks and catchphrases. First of all, these should seem authentic. If at first these don’t seem to fit the character, they should become more meaningful as the character develops. They should not feel bogus, as if the author added them to lure the reader into the story. They should serve a purpose in terms of the plot or the character(s). If possible, they should not be stereotypical.

Here are a few quirks that readers might notice, accept, and remember: 1) always looks away and then back before speaking; 2) wears red cowboy boots with every outfit; 3) likes to one-up people; 4) snorts when laughing; 5) regularly eats much slower than everyone else; 6) sits upright even in a reclining chair; 7) can do a few magic tricks; 8) is never punctual; 9) over-describes things, keeps adding details; 10) argues a lot (“yes, but”) for no particular reason.

Sometimes catchphrases are words the character regularly uses from another language, such as “Vite! Vite! Vite!!” Sometimes, they are a particular way of saying a word or phrase, such as “ab-so-LUTE-ly” or “dy-no-mite!” Sometimes, they are a word or phrase from popular media, such as “Come on down” or “How sweet it is” or “Just one more thing” or “Is that your final answer?” or “Sock it to me.” The key, again, is to use catchphrases that seem authentic and serve a purpose in the story.

- Objects in the character’s environment

Readers are apt to notice a character who is almost always in an environment characterized by something interesting or accompanied by a noteworthy object. Remember, however, that this object must fit some aspect of the character (be authentic to the character) and serve a purpose. These pictures might give you an idea about what to use to make a character memorable. . .as long as the item fits the character and serves a purpose in your story.

Here are some objects to spur your imagination:

Here are some objects to spur your imagination:

A FEW CAUTIONS ABOUT DIRECT AND INDIRECT CHARACTERIZATION:

1. Beware: Direct characterization can easily lead to telling rather than showing.

2. Beware: Indirect approaches can be tedious and boring. The reader might wonder why the author has not just said, “He was shy. . .or angry. . .or humiliated. . .or hopeful” and gotten on with the action.

3. Balance is the key: Use the direct approach when concision is needed; use the indirect approach when some activity will impart what the writer wants the reader to understand or feel.

4. If you sense you are doing too much of one, you probably are.

5. Beware the McGuffin:

THE MACGUFFIN

THE MACGUFFIN

This is “an object, event, or character that serves to keep the plot in motion despite lacking intrinsic importance.” Example: “The missing document is a MacGuffin that sends two spies racing around the world, but the real story centers on tension between them.

“The first person to use ‘MacGuffin’ as a word for a plot device was Alfred Hitchcock, who borrowed it from an old shaggy-dog story in which some passengers on a train interrogate a man carrying a large, strange-looking package. The man says the package contains a ‘MacGuffiin,’ which is used to catch tigers in the Scottish highlands. When the group protests that there are no tigers in the Highlands, he replies, ‘Well, then, this must not be a MacGuffin.’ Hitchcock apparently appreciated the effect of the mysterious package and recognized that an audience would continue to follow a story even if the initial interest-grabber turned out to be irrelevant.”

(Text from Merriam-Webster’s 365 New Words Calendar, www.pageaday.com. Image by catalyststuff on Freepik)